I just finished Chapter 22, “Marriage and Loneliness”, in John Trevor’s autobiography, My Quest for God. In this chapter, Trevor struggles with balancing the security of marriage and work with the desire for spiritual growth. On the one hand, he explains that marriage grounded him in a way he had never been before:

“It was only when I was married that I knew what ease and repose meant. All through my life the genial sunshine of existence had been denied me. I had lived through almost every experience but that of home-happiness, and the settled peace and freedom it brings.”

I felt the same way getting married. As much as I am intellectually repulsed by the notion of needing another person to “complete” you, that is exactly the way it felt to me. I wonder if I would have ever been able to grow beyond certain insecurities if I had not met and married my soulmate.

On the other hand, Trevor complains of the stagnation which is cultivated by domesticity:

“At Meadville I remember being forcibly struck with the hopelessness of the married students for reform. There was a good deal of static force about them; no dynamic. … They always talked of Peace, and Love, and the recognition of Facts, and the growth of the Spiritual Life. While I was burning for some hot Crusade against the Conformity, the Conventionality, the Compromise which were paralysing Unitarian work, these married students saw nothing wanting but the cultivation of all the graces in a hot-house.

“Of course the married life is itself a kind of hot-house wherein the tenderer graces grow very comfortably; and of course it was just what I needed to reduce to sanity my already too rampant nature. The danger of marriage to me lay in its tendency to make me unduly sane; to give me a sanity which was incapable of movement or direction.”

I understand Trevor’s ambivalence. Through marriage and all that came with it (house, children, job), I grew roots. Which is a good thing. But the same thing that grounds me, also binds me. Trevor, at the age of 27, writes to his wife who is away:

“here I am, settled in business, settled in my work, a wife, a child, to call my own, and now the best moment of all has come”

and yet …

“I have been feeling that my life is wanting in the moral element, that there is no real earnestness and self-sacrifice in it, no devotion to anything which will ennoble my existence”

For Trevor, a great deal of this angst had to do with his choice of profession. He was trained in architecture, but had no real passion for it. What he wanted, was to become a writer or a preacher. He writes to his wife:

“I was thinking this morning that if I were not married I should love to throw up Architecture, and live as economically as possible until I could make money by writing. Probably it is well for me that I cannot follow my own devices; but my heart is in writing, and I don’t care a little bit about Architecture.”

“I am getting unhappy at not being able to write, and fear that it will have a very depressing effect on me. I seem to have no outlet, and am engaged in work which is not natural to me.”

Ultimately, Trevor sells his architecture business and moves away.

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a chemist (because I got a chemistry set one Christmas), an astronaut (like every kid), a business man (like my Dad), and probably a lot of other professions I don’t remember. Today, I’m a lawyer. I practice what is called “insurance defense”. I represent insurance companies and people who insurance companies insure. I work for “the man”. I am a cog in the machine.

I actually had big dreams when I decided to become a lawyer. I wanted to be a Constitutional lawyer, whatever that it, I wanted to argue Bill of Rights cases in front of the Supreme Court. Then, when I got into law school, I decided that the best way to practice Constitutional law was to get into criminal law, specifically to become a prosecutor. But after law school, I went to work for a judge in civil court. I was desperate for a job, and I was kind of lost. While working there, I discovered I had an affinity for insurance defense practice. The fact that I could eventually make six figures doing that kind of work made the prospect even more appealing, especially as we had just had our second child and the practical realities of putting a roof over our heads hit had finally home with graduation, after six straight years of schooling. At every step of the way, I got further and further away from my original intention, which was to change the world.

I am good at what I do. Law school came very easily to me and I graduated in the top 10% of my class without trying very hard. Legal writing is my forte. I’ve always had a bit of a flair for the dramatic, so I do well in front of a jury too. Every day presents me with a different challenge, so my job is rarely boring. And my job affords me a measure of the financial security I desired growing up, and a fair amount of leisure time to spend with my family and to pursue my interests, like this blog. Nevertheless, I can’t get over the feeling some days that I sold out.

I felt this acutely when a Buddhist Unitarian I attend church with recently mentioned “Right Livelihood” as one of the tenets of the Buddhist “Eightfold Path”, together with Right Speech and Right Action. And I wondered if my chosen profession would qualify as “right livelihood”.

I remember reading an article in undergraduate school called “The Parasite Economy” which explained how lawyers and lobbyists are a drain on the economy, because they do not create anything. Instead, two lawyers will spend $1.98 together fighting over $1. And my branch of the law is particularly problematic, because it basically consists of helping insurance companies keep their money, instead of giving it to people who may (or may not) be hurt. In short, I feel a real disconnect between my livelihood and my spiritual ideals.

Could I do some good with my degree? Take some pro bono cases for example? The problem is that I don’t enjoy that work. I enjoy what I do. I don’t enjoy helping people. (There, I said it.) I have taken on pro bono cases in the past, and frankly I hated it. I worked for a while on the other side of the bar too, as a plaintiff’s attorney. And I hated that too. I’m good at what I do, and for the most part I enjoy it. My job fits me, my aptitudes and my personality. But I create nothing. And I do not help to make the world a better place.

Of course, there is some dignity or nobility in “the law” in an abstract sense, which my wife reminds me of when I get too pessimistic about my career choices. But it is only at high levels of abstraction that I can feel that way about what I do. So here I am. I am where I belong. And in that sense my livelihood is “right” for me. But I do not like my place in the world. As a youth I dreamed of changing the world. Now I perpetuate a system of conflict resolution which could only be called a “justice system” in a very ironic sense.

I actually remember making this choice, years ago in undergraduate. I had an opportunity to choose an academic career. But I wanted to make money. I wanted to raise a family with a certain level of financial security, one that my parents struggled to achieve when I was a child. Since becoming a lawyer, I have fantasized about what it would have been like to get a degree in Religious Studies and become a college professor. Then I saw this hilarious video, and decided maybe I had made the right choice after all.

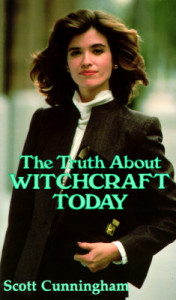

I don’t have an answer for this dilemma. I know this is not an uncommon feeling. And I know it’s probably not a coincidence that I am 36 this year, approaching the half-way point of my statistical life expectancy. But most people in my situation are not Pagan, and most Pagans are not in my situation. I have totally bought into the white suburban middle-class picket fence dream. Where is the radicalism? Where is the danger? Where is the romance? My situation reminds me of that cover to Scott Cunningham’s The Truth About Witchcraft Today, with the conservatively dressed young woman who looks like anything except a witch.

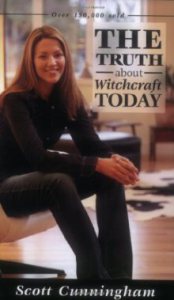

Or here’s a more recent edition:

These covers say, “Nothing radical here folks!” If I were female, that could be me. The irony is that I have elsewhere advocated for mainstreaming Paganism. So what am I complaining about? Isn’t this what I wanted? A nice, suburban, middle-class Pagan family. But something in me says, “blech!”

Trevor writes:

“The half fanatic I once was and the half worldling I now am must unite, and for the future years of our union make for thee and ours a full-hearted man.”

I, like Trevor, need to bring together the radical and the “worldling” in one heart. Trevor does that by leaving his profession. But Trevor felt that architecture was unnatural to him. I feel the opposite about being an insurance defense attorney. But I share Trevor’s desire for a life of dedication to a higher cause.

Trevor’s next chapter is entitled “Into the Wilderness”. Those words resonate with me and I feel a premonition that perhaps I too need to go into some kind of “wilderness” to find my direction.