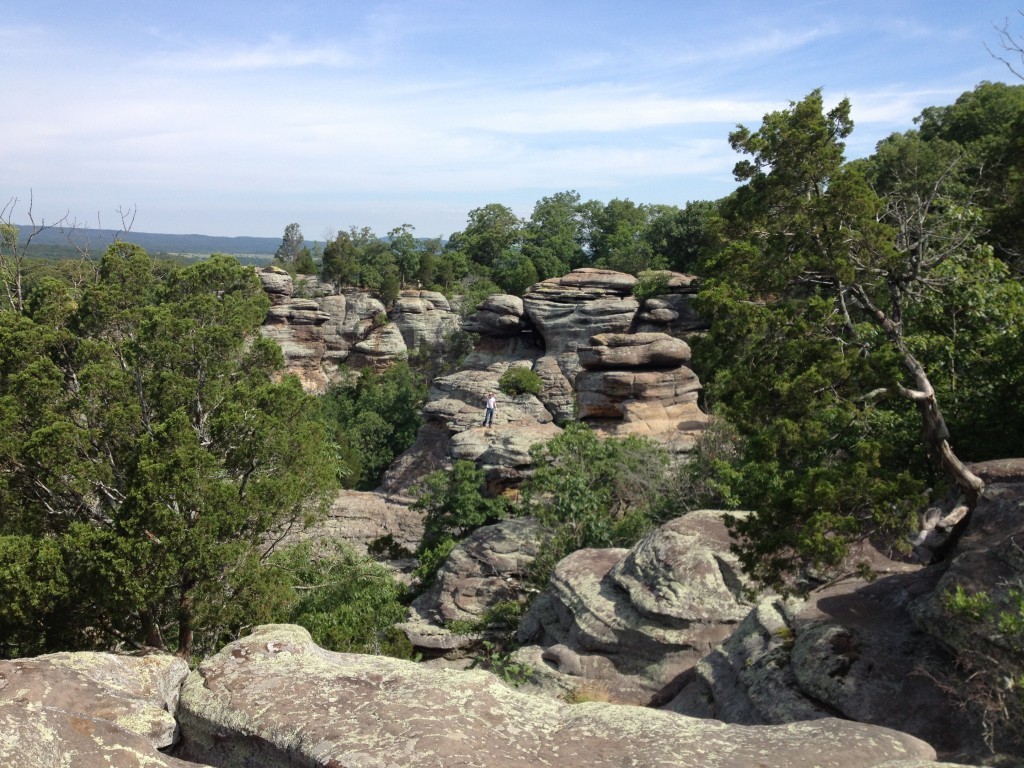

The following summer solstice, I went on a camping trip with my family at the “Garden of the Gods” in the Shawnee National Forest in southern Illinois. It was hot, even in the shade. My 11-year old daughter was freaked out by the many, many Daddy longlegs. And my 15-year old son griped incessantly … before, during, and after our four hour hike. Then we got lost on the hike and had to turn back (I hate turning back). I had forgotten the camp chairs, which made sitting around the fire afterward less than comfortable. And then, on the way back home, we realized we had gotten into poison ivy. It might have made me wonder why we drove 12 hours round trip for this.

But in fact, even while I sat at home scratching my poison ivy, I never once regretted the trip. I enjoyed every minute of it. And I wondered what it was about this experience that that I found so satisfying. The vistas were beautiful. We saw some fascinating rock formations, and I loved climbing on the rocks. But it was more than that. It wasn’t like I had any profound “double rainbow experiences” this time (see Part 3), but there was something similar to my experience in Muir Woods. Before the trip, I felt a profound longing to get into the woods again. While we were there, I felt like I was right where I needed to be. And when we left, I felt really satisfied … kind of like I had eaten a really good meal, but in a spiritual sense.

I have a theory for why this is. My everyday world is an instrumental world. Everything has a function for me, easily controlled. Everything is a tool, things available for my use. My everyday world appears to me not as itself, but as a resource for my appropriation. When I go into the woods, though, I encounter a world that is there, not for me, but for itself. It is a world that seems much more indifferent to my existence than the ready-made world of tools I left behind. Because of this, in the world of the woods, my sensual self takes the forefront, and my intellectual self takes a back seat. My primary experience of the world in the woods is direct and participative rather than abstract and instrumental.

This, I think is why I enjoy hiking so much. For me, hiking isn’t about walking to get some place. I walk to walk, to be in the woods, to feel myself in my own body, to throw myself up against the physical world, to strain against the limits of my physicality, limits which foreshadow the Limit which is placed on every life. This is why I leave the woods feeling satisfied, like a hunger has been sated — because it has: a soul-hunger, a hunger for direct, sensory-rich contact with the world.

It occurs to me that the line between my ordinary instrumental world and the sense-rich world of “nature” is a very subjective one. For one thing, I was in a national park, which is only “wild” by a matter of degree. A lot of the national park was “instrumentalized,” so to speak. We drove in on paved roads. We camped in a prepared campsite. Water was available from a pump. There were latrines. We hiked on trails which were marked (although not well apparently). But, in spite of this, the world of the woods was different enough from my everyday experience that I could transition from my instrumental mode of being to the participative mode of being.

To one person, farmland might seem “wild,” at least in comparison with the urban setting they might be more familiar with. To another person, a state park may be more of a human environment than a “natural” one. Is this why children seem to have so much wonder at our mundane world? It has not yet become instrumental for them; they have not yet learned to control it, and so, they have not forgotten how to see it.

If the difference between these two worlds is merely a matter of degree, and if the distinction is largely subjective, then perhaps it is possible to experience the participative mode of being in my everyday world. Perhaps all that is required is “unfamiliarizing” myself with that everyday world. There is so much that I take for granted, that my gaze passes casually over, that I rush past. There are birds and trees and dirt and worms and sunlight and wind just outside my air-conditioned office window. I walk by these things every day. I see them through the glass windows of all of my little cages: my home, my car, my office.

Would it be possible to stand in my suburban yard or even in an asphalt parking lot and have the same sensual experience of participation that I have in the woods? It would be more difficult, but not impossible, I think. So this was the challenge I set before myself: “to explore the neighborhood” as Annie Dillard says — figuratively and literally — to find the “garden of the gods” in my own backyard, in the neighborhood retention pond, in the parking lot of my office building.

To be continued …