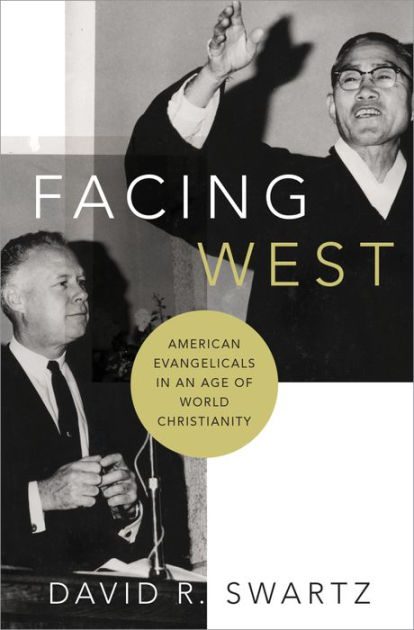

A couple of years ago on a Sunday morning, I landed at Logan Airport and took a train to Boston’s South End. I was wrapping up research for what became Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity. Mostly about the activities of American missionaries abroad—and how they were shaped by these encounters—the book in its final chapter focused on how global encounters were increasingly happening at home through African, Asian, and Latin American immigration.

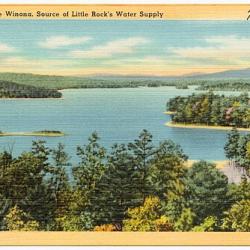

I ended up that morning at the intersection of Shawmut Avenue and Lenox Street in a historic neighborhood where George Washington fought Redcoats in 1775. Nearly 250 years later, it was a different universe. On three of the four corners stood nonwhite churches, each pulsating with energy. The Shawmut Community Church of God, a historic African-American church, occupied the south corner. Fuente de Vida, a Pentecostal church founded in 2006 by Puerto Ricans, but also full of Dominican, Cuban, and Guatemalan members, stood on the north corner. The Redeemed Christian Church of God Cornerstone Miracle Center, a five-year-old Nigerian congregation, was on the east corner.

I ended up that morning at the intersection of Shawmut Avenue and Lenox Street in a historic neighborhood where George Washington fought Redcoats in 1775. Nearly 250 years later, it was a different universe. On three of the four corners stood nonwhite churches, each pulsating with energy. The Shawmut Community Church of God, a historic African-American church, occupied the south corner. Fuente de Vida, a Pentecostal church founded in 2006 by Puerto Ricans, but also full of Dominican, Cuban, and Guatemalan members, stood on the north corner. The Redeemed Christian Church of God Cornerstone Miracle Center, a five-year-old Nigerian congregation, was on the east corner.

As I entered the sparsely decorated Cornerstone Miracle Center, sixty sets of eyes turned toward me. An elegant woman, wearing a white shift-style dress with colorfully woven edging, greeted me. Clearly delighted by my arrival, she showed me to a row near the front of the large room. An elderly man seated in the row behind me wore a pale blue robe with a fez-like cap on his head. His daughter, introducing herself as Mummy Tolu, wore fashionable horn-rimmed glasses and a garment made of crisp purple fabric. A man in the row in front wore jeans and an untucked polo shirt. As he worshiped with hands high in the air, a smartphone and a Nigerian keychain rested on his chair.

“We are a church of all nations,” explained Pastor Yinka Aina from the stage. “When you leave, speak what you want,” he said, “but now we want to speak in one language.” The English-language service that followed consisted of enthusiastic singing and passionate prayer. At one point, the entire congregation, each member’s arms outstretched, surrounded me as the pastor prayed that the “Holy Spirit grant the desires of his heart.” A rousing sermon, also on the topic of the Holy Spirit, urged the congregation to feel and practice God’s power. “We are not in the mortuary. We are in the sanctuary!” he exclaimed. “Sing unto the Lord a joyful song. Get ready to dance!”

The intersection of Shawmut and Lenox represents a nexus of multicultural Christianity in Boston. Dozens of vibrant congregations radiate out from the Cornerstone Miracle Center through the South End. One block to the south is CrossTown Church International, a Pentecostal “apostolic epicenter” with branches in Trinidad and Zimbabwe. Another block to the east is the 1,500-member Congregación León de Judá, a Latino Baptist congregation founded in 1982. The north end of the South End is the site of Cornerstone Boston, a Korean congregation affiliated with the Evangelical Covenant Church; Emmanuel Disciples Fellowship, an Ethiopian Baptist church; and the South End Neighborhood Church, a congregation made up of whites, African Americans, and several other ethnicities. Of the thirty-three churches in the South End, only four are predominantly Anglo. While most worship in English, others speak and sing in Spanish, Amharic, Haitian Creole, Greek, Korean, and Mandarin. Fully one-third of them were launched after 2000. They are located in hotels, community centers, and obscure storefronts. Most maintain only a rudimentary presence online. They may be hidden, but they defy conventional wisdom that Boston is unrelentingly secular.

Evangelical Bostonians call it the “Quiet Revival.” The number of churches, as tracked by the Emmanuel Gospel Center, a booster of this multicultural renewal, has doubled since 1969, from 300 to 600. This represents remarkable growth considering the stagnation of Boston’s population and flight of white churches to the suburbs. Since the 1990s, the pace has only accelerated. In the first decades of the twenty-first century, one sustainable church was launched every few weeks, almost all by immigrants.

The results of the 2020 census, released last month, confirm what I experienced on my trip to Boston. “Our analysis of the results show that the US population is much more multiracial, and more racially and ethnically diverse than what we measured in the past,” said Nicholas Jones, the director and senior advisor of race and ethnic research and outreach in the US Census Bureau’s population division. The United States is on pace to become a majority-minority nation by 2045.

Here is the data for Boston: The number of non-Hispanic whites dropped from 47 percent in 2010 to 44.6 percent in 2020. The portion of Black residents also fell, from 22.4 percent in 2010 to 19.1 percent. At the same time, the portion of Asian-Americans rose from 8.4 percent to 11.2 percent, and the portion of Hispanics rose from 17.5 to 18.7. The numbers are more dramatic in other regions of the United States.

The rising non-white population has stanched an overall decline in numbers. As young people migrated to the suburbs and to the south and west for jobs and less expensive housing, Boston’s population has rebounded. According to the Census Bureau, it grew 12.1 percent between 2010 and 2020. This is double the growth rate of Massachusetts.

The implications for urban religion are significant. In a follow-up post, I’ll discuss what this might mean for evangelical politics, theology, and culture. But for now, I simply want to point out that immigration is saving American Christianity from demographic collapse. As the white West secularizes, much of the Global South remains highly religious. At the turn of the twentieth century, less than 20 percent of Christians worldwide were nonwhite. At the turn of the twenty-first century, over 79 percent were nonwhite. By 2015, according to Gordon-Conwell’s Center for the Study of Global Christianity, 84 percent were nonwhite. From 1970 to 2010, the evangelical population grew about six times faster in regions outside North America.

So it should not be surprising that many immigrants to the United States are Christian. In fact, according to scholar Jehu Hanciles, himself an immigrant from Sierra Leone, nearly two-thirds of immigrants are Christian. Through the 2010s, more than 600,000 Christian immigrants received green cards each year. Of course, non-Christian diversity also spiked in in the decades since the Immigration Act of 1965, but the new immigration, notes sociologist Stephen Warner, is bringing about “not so much a new diversity among American religions as diversity within America’s majority religion.” The striking story is that as the United States becomes less Christian by the attrition of Americans with European heritage, it becomes more Christian through non-white migration. “We’re witnessing the re-Christianization of America,” writes scholar Gastón Espinosa. And nowhere has this demographic transformation been so dramatic as Boston. Four hundred years after the Puritans, some evangelical observers again see Boston as a “city on a hill.”

This flies in the face of much handwringing about the secularity of Boston and New England more broadly. By the 2000s, Christians from the burgeoning Sunbelt described the spiritual climate as “incalculably colder than the lowest lows of a Boston winter.” Southern Baptists, once the mortal enemies of New England abolitionists, launched a missionary offensive to save the region from liberalism and secularism. But they found it to be rough going. “About once every hour, I give up. It’s tough, man,” said Pastor Joe Souza to a CBS reporter. “It’s like you found a cure for cancer and you want to give it away and nobody wants it.” New England, they say, is a graveyard for church planters.

But that’s only true if you’re looking for Anglos worshipping under white steeples. The 2020 Census results—and the story of immigration in Boston—offer some hope to a religious tradition recently devastated by sex scandals, abuses of power, and declining numbers. Perhaps it will even prompt evangelicals to question the wisdom of voting for a nativist president bent on stopping a source of their revitalization.