As I was preparing last week to lead a graduate seminar discussion of Amy Louise Wood’s Lynching and Spectacle, I ran across an especially disconcerting passage. Since Wood’s book is a study of the way in which large-scale acts of mob violence and torturous executions of African Americans were occasions for community celebration and commemoration, one might assume that the entire book would be disconcerting – as indeed, to some extent, it was. But the passage that especially caught my attention focused not on the horrific nature of lynching itself but on the fear that southern white ministers had about speaking out against lynching.

“A 1935 questionnaire answered by some 5,000 ministers showed that only 3.3 percent had preached or worked against lynching in some way,” Wood states (Lynching and Spectacle, p. 51). “Most simply felt that lynching was ‘inevitable’ and that, in taking a stance, they would divide and alienate their congregations.” Wood then gives an example of a Texas Methodist minister of the 1920s who was warned that if he preached against a local lynching, he would be embarking on a course of action that was “unsafe” for him personally.

Most pastors today don’t have to agonize about whether to speak out against lynching, because few people now doubt that it’s evil. But the fact that southern white ministers did agonize about this 85 years ago – and that the vast majority chose to remain silent rather than risk upsetting their congregations – indicates how difficult it is for clergy to speak out against the favorite sins of their community, even when the sin might seem so obviously wrong as racially motivated public killing.

Many of these pastors believed that lynching was wrong, because their denominations condemned it. Only the year before, in 1934, the Southern Baptist Convention had passed a resolution “reaffirm[ing] its unalterable and unsparing condemnation of lynching.” “We urge our pastors and churches to take a firm stand against this evil,” the SBC proclaimed. And, of course, in some churches outside the South – and in African American congregations everywhere – the gospel of Jesus was often cited in condemnations of lynching. Christianity, at least in its official ecclesiastical form, seemed firmly opposed to such violence.

But preaching against lynching proved to be easier said than done. In January 1931, only one pastor in Maryville, Missouri, dared to say anything about a local lynching that occurred that month. A white mob in the small town had taken Raymond Gunn – an African American accused of the murder and attempted rape of a local schoolteacher – and then chained him to the top of the schoolhouse roof, doused him with gasoline, and burned him for eleven minutes, destroying the school in a conflagration that took Gunn’s life and reduced his body to ashes. Burning a man to death might have seemed horrific – indeed, it received strong condemnation in newspaper editorials across the country – but when the Federal Council of Churches surveyed ministers in the town, they found that all but one had steered clear of the matter in their sermons immediately following the lynching. One Maryville pastor devoted his sermon the next Sunday to the “necessity of Christians giving evidence of the grace of God in their daily living,” while another used his Sunday message to appeal for funds for international mission work, as an article published in the Journal of Negro History (1957) reported. Some pastors began circulating a petition in the town during the week after the lynching – but the petition had nothing to do with the mob violence. Instead, it was a petition to close the town’s pool halls.

As I thought about why pastors in the South were so fearful to address the sin of lynching, even when their denominations gave them the charge to do so, it occurred to me that these pastors were dealing with a conflict between two versions of the Christian religion – on the one hand, the religion officially taught by their denominations, and on the other, the popular regionally shaped religion of the community. According to the official ecclesiastical version of Christianity, as taught in seminaries and propagated in denominational resolutions, lynching was wrong. It was mob violence. It was killing that took place outside of the law. Even if the southern denominations that spoke against lynching were still all-white bastions of racial privilege, they did not countenance dousing men in gasoline and watching them burn to death as a public spectacle.

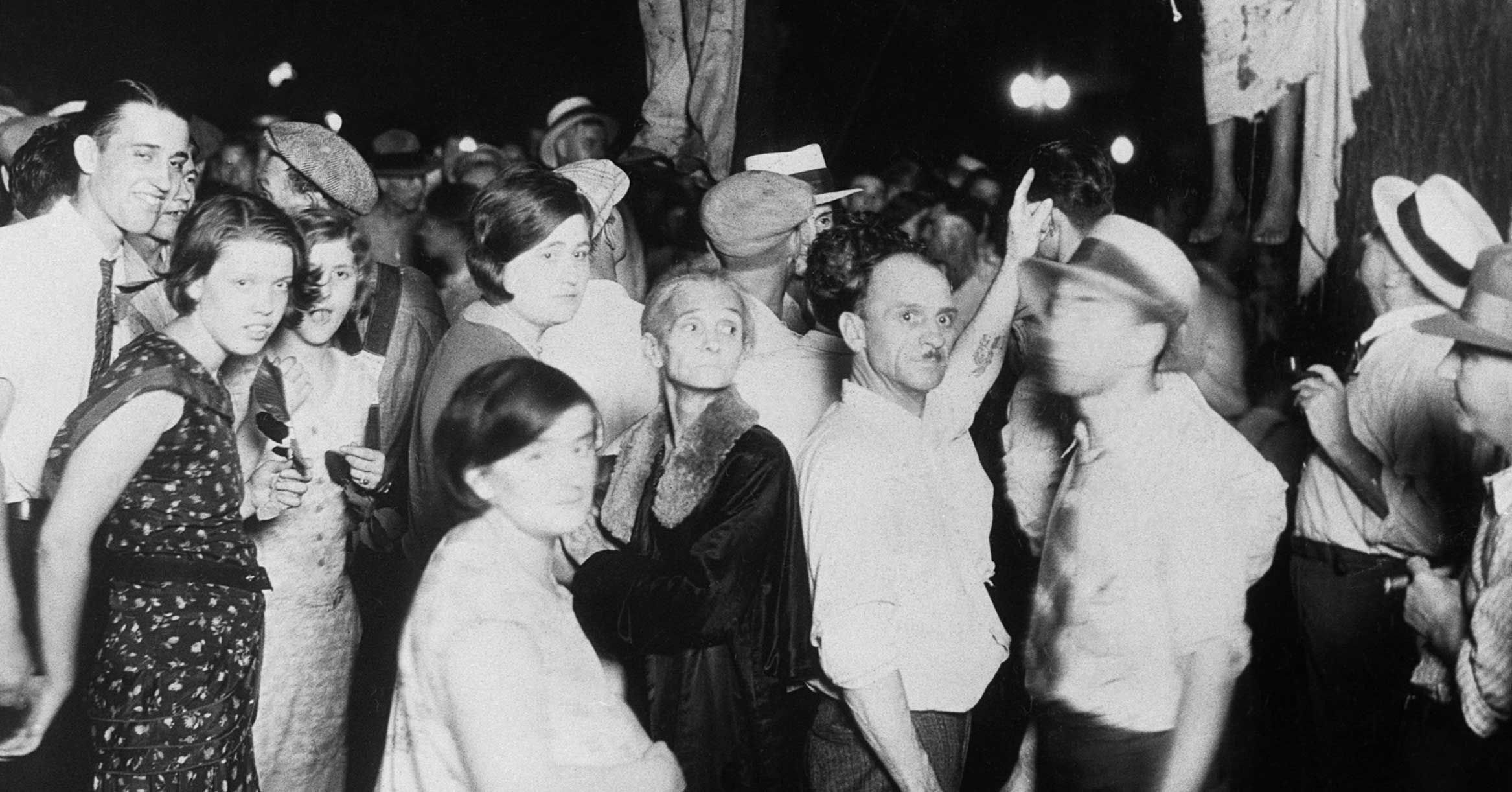

But in many rural areas and small towns, Christian people not only countenanced this in the early 20th century but lauded it, on the grounds that no punishment was too harsh for a Black man who raped or murdered a white woman. They were engaged in the work of God when they participated in these righteous acts of vindication of the victim, they thought. It was their Christian duty to stand up against injustice in their communities by purging the iniquitous person from their midst in a fiery conflagration or a torturous execution. Though mixed with a massive dose of white supremacy and an ethos of private violence and personal vengeance that might have seemed extremely difficult to square with the teachings of Jesus, this popular religion of southern rural areas took on the authority of gospel – and, indeed, carried more weight than any genuine evangelical message. Lynching, for these participants, was a Christian duty. There was no Christian creed that suggested that lynching was godly work, but for many white Christians in the early 20th-century rural South, the anger they felt about alleged violations of the racial and sexual codes in their communities felt so righteous that they were sure that burning the transgressors to death was the will of God. No denominational resolution could convince them otherwise.

For pastors in these regions, it was safe to preach against alcohol. It was safe to preach against adultery. It was safe to preach against lying or stealing. All of these were sins in both the ecclesiastical and popular versions of Christianity. But it was not safe to preach against lynching. Such preaching revealed the fault lines between the ecclesiastical and popular versions of Christianity, and most ministers knew that if forced to choose, their congregants would not hesitate to dismiss the minister (or worse) rather than give up their cherished beliefs.

“If there were a drunken orgy, I would bet ten to one that a church member was not in it,” Reinhold Niebuhr, one of the most influential American Protestant theologians of the 1930s, wrote. “That is long odds, but on the whole I would assume a church member was not in it. But if there were a lynching I would bet ten to one a church member was in it” (cited in Robert Moats Miller, “The Protestant Churches and Lynching, 1919-1939,” J. of Negro History 2 (1957): 118). Southern ministers knew that, too. So, although there were a few notable exceptions, the majority chose not to talk about such a controversial subject.

But eventually lynching ceased to be a divisive topic for churches, and today most people – even white southerners in rural areas that once supported lynching – find it hard to imagine a time when so many considered lynching a Christian duty.

Yet the reasons why southern pastors of nearly a century ago were inclined to remain silent about lynching are closely parallel to the reasons why many pastors agonize over whether to speak out on controversial issues today. There is often a conflict between the values of ecclesiastical Christianity and the beliefs of popular Christianity. Ecclesiastical Christianity might warn against Christian nationalism; popular Christianity embraces it. Ecclesiastical Christianity might condemn unsupported political conspiracy theories; popular Christianity makes such theories part of its religion. Ecclesiastical Christianity might include concerns about gun violence and support for gun control (as a United Methodist Church resolution did in 2016), but popular Christianity (even in rural Methodist churches) makes Second Amendment claims a part of its faith and practice. Ecclesiastical Christianity might support racial justice and collective repentance for racist actions, even when this goal conflicts with right-wing politics. Popular Christianity, on the other hand, condemns Critical Race Theory, even when these condemnations alienate other Christians. Ecclesiastical Christianity, in some cases, has been supportive of the concerns expressed in Black Lives Matter protests. This has not necessarily been the case with the versions of popular Christianity found among white conservatives.

In general, ecclesiastical Christianity is more likely to align with the values of an educated, urban middle class, at least on some questions. This is true today, and it was certainly true during the lynching debate of the 1930s. For that reason, it is easy for champions of the popular version of Christianity to condemn it as a liberal heresy – as many people have done with the debate over Critical Race Theory, for instance.

But there’s more to the story than that. In most of the areas in which popular Christianity comes into conflict with ecclesiastical Christianity, it is not simply contending for the “faith once for all delivered to the saints,” even though its adherents believe this. Instead, it is contending for the traditional values of a region and a culture that have been imported into Christianity but were never a comfortable fit for the gospel. The clearest evidence of that is that the issues that most animate the adherents of popular Christianity are issues that large numbers of non-Christians with the same political views also support. Lynching had equal appeal for churchgoing moralists and profane swearers and drunkards in the rural South. When a white mob burned Sam Hose to death in Newnan, Georgia, in 1899, one man in the crowd shouted “Glory!” as though he were at a Methodist revival. But many others in the crowd had been drinking heavily and did not seem to approach the flaying and killing of their victim as a religious act. In the same way, the issues that popular Christianity in the rural South has appropriated as its own are really not uniquely Christian, even if they have been baptized as such. Support for Second Amendment rights, patriotic jingoism, and white nationalism have widespread appeal among many people who never go to church. One doesn’t have to be a Christian to be a gun-toting defender of “God and country.” Indeed, this theology of popular Christianity seems to work better outside of church than within it, which is why it’s at odds with the ecclesiastical theology of most denominations – including even the Southern Baptist Convention, which largely repudiated some aspects of this ideology in a narrow vote at its annual meeting earlier this year.

Of course, gun control, demilitarization, and racial justice also have widespread appeal among secular people – which means that these issues, too, are not uniquely Christian. And if adherents of ecclesiastical Christianity simply appropriated secular political platforms and brought them into the church under the guise of Christian teaching, that would be problematic. But I think that when adherents of an ecclesiastical version of Christianity base their concerns about gun violence on scriptural statements about the high value of human life or when they call for racial justice using scriptural teachings about God’s vision for human reconciliation, they are demonstrating that these causes, while embraced by many who do not share their Christian faith, are a natural outgrowth of a deep understanding of the gospel. That’s more than I’ve seen from defenses of the popular version of a religion of “God and country.” And it’s certainly more than the advocates of lynching were able to provide in the early 20th century.

It is when we examine the rival theological claims of ecclesiastical and popular Christianity that the differences between the two versions of a common religion become apparent. Popular Christianity’s justification for lynching consisted of a loud denunciation of rape. On that, ecclesiastical Christianity could agree: Rape is wrong, and it should merit outrage, because it is a deep violation of an image-bearer of God. But what white adherents of popular Christianity in the rural South were unwilling to do in the 1930s was to engage in some deeper soul-searching about the reasons why their own version of the faith seemed to be so outraged by alleged Black rape against white women while saying nothing about white rape of Black women. It failed to ask whether acts of popular vengeance in the name of justice were compatible with a gospel that had so much to say about forgiveness – and that strongly condemned personal vindictiveness. It failed to say anything about the spiritual blindness of people who would take delight in burning a man to death and collecting scraps from the charred rubble to save as souvenirs of the killing – all in the name of righteousness.

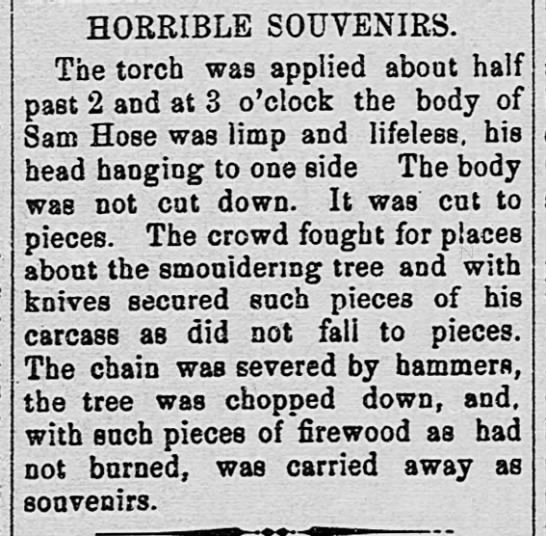

(Newspaper report of the lynching of Sam Hose, Newnan, GA, April 1899)

Eighty-five years after the fact, it might be easy to condemn the cowardliness of ministers who were afraid to anger their congregants by preaching against lynching. But whenever two rival versions of Christianity come into conflict, it’s very difficult for a pastor to win people over through a single sermon alone. I’m not sure that I can blame the ministers who refused to say anything about Raymond Gunn the Sunday after he was burned to death, because I think that preaching about this matter on that particular day might not have won anyone over to their point of view. But I would say this: Their refusal to systematically and deliberately challenge the popular version of Christianity that made support for lynching part of its creed resulted in horrendous consequences for the church that, to a certain degree, we are still paying. If ministers had systematically confronted their congregants with the contrast between a regional popular version of Christianity based on private vengeance and racial hierarchy and the message of Jesus that was based on a very different set of values, maybe the outcome would have been different. Maybe the anti-lynching movement among churches would not have been confined to a few educated urban congregations, but would instead have become a groundswell of opposition that would have overwhelmed the popular religion of the rural South by transforming its adherents into true believers in the gospel.

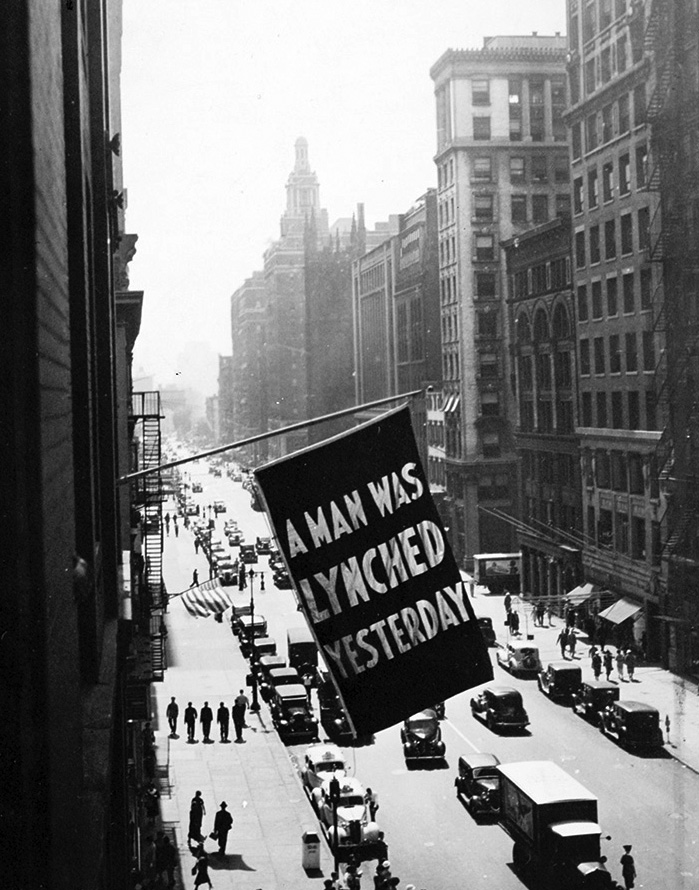

(Library of Congress: Photo of the NAACP headquarters, NYC, 1938)

But that might have required a transformation in the ecclesiastical version of Christianity as well. As long as the ministers who adhered to ecclesiastical Christianity viewed opposition to lynching as merely a Christian option and not as a necessary consequence of the gospel itself, it was easy to ignore the denominational resolutions on lynching when preaching on them would have been too risky. Far better, it seemed, to talk about the evidence of grace in a Christian life. But if they had seen opposition to lynching as an absolutely essential evidence of that grace, maybe their preaching would have been different. Maybe they would not have waited until the fiery death of Raymond Gunn to say something. Maybe they would have already been working with their congregations to exchange the prejudices and presuppositions of the region’s popular region for a gospel-centered Christianity that was far different than any of them imagined.

And so, today, ministers who sense the difference between the popular religion of their congregants and a genuinely Christian gospel face a choice: Will they speak up on an issue that falls along this fault line or will they remain silence out of fear of offending their congregation? It’s not an easy choice – and it probably cannot be resolved in a single sermon. But those who sense the difference between the popular Christianity of their regional culture and the biblically centered, historic teachings of the Christian church can decide whether they will spend their pastoral career attempting to draw their congregants to a holistic understanding of the gospel or whether they will acquiesce to the cultural norms of the region. If they choose to acquiesce, their actions may look in retrospect like the actions of the ministers of the 1930s who were too afraid to say anything about lynching. But if they speak up and choose to challenge their congregation with the gospel, one can only imagine how differently the story might turn out.