“All Jews, Christians and Moslems, the spiritual heirs of those slaves freed from Egyptian bondage, are bound by that law, whether they live in the Middle East, in New York — or in California.” Rabbi Joseph B. Glaser (Food & Justice, July 1986, 11).

We are about a week away from the start of Hispanic Heritage month. However, lately in my reading I have been somewhat focused on Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations. How could I possibly write about all the above?

I decided to meditate a little bit on how Cesar Chavez was able to foster a spirit of ecumenicalism within the UFW (farmworkers union). I pulled out my copy of Mario T. García’s The Gospel of Cesar Chavez for inspiration. As the cover image of this post illustrates, the Catholic Chavez publicly celebrated Yom Kippur in 1971.

Images of interfaith meetings seem so innocuous and commonplace in the American mainstream today that they don’t shock anymore. We forget that the spirit of contemporary ecumenical dialogue came with the tragedy of WWII and the horrors of the Holocaust behind us—history’s reminder of humanity’s dark side.

The war ended in 1945. As a good Catholic, Chavez would see the epic changes that transpired with Vatican II (1962-65), particularly in the Church’s relationship to Judaism. In fact, Garcia points out that Chavez “believed in ecumenism and brotherhood with people of other faiths (García, 135). Post-war Christian dialogue with Judaism took on a new turn, based on the open acknowledgement of centuries of antisemitism infecting Christian history.

The most famous Jewish intellectual and spiritual leader in American history in this post-war period was Abraham Joshua Heschel. He publicly stood with Martin Luther King Jr. at the Selma march. His daughter, the scholar Susannah Heschel, writes beautifully about their relationship. If you take a deep dive in this history, you will realize that King and the Civil Rights Movement had enormous support from the American Jewish community.

What about Cesar Chavez and the UFW? It seems that the American Jewish community, in fact, was a very active supporter of Chavez and the farm workers. Rabbi Dr. Shmuly Yanklowitz’s article “The Forgotten Story of Cesar Chavez and the Jews” pretty much sums up the lack of historical knowledge we have about this legacy.

(It never ceases to amaze that important stories like these often get labeled as “forgotten.” How bad is our historical memory? This history is not even over 100 years old yet.)

The article points out a few key American Jewish figures, both internal and external supporters of the UFW. For example, Rabbi Glaser, quoted at the beginning, was a key mediator between the UFW and its opponents. Rabbi Yanklowitz claims that it was common in Jewish households to not purchase grapes because they were supporting the farmworkers and the boycotts.

Chavez oftentimes chided his own Catholic tradition, and some of the hesitancy of local priests to speak publicly about the farmworker’s struggles, by pointing out the support he received from Protestants and other faith traditions. Chavez’s ecumenical spirit can be seen in the way he refers to Moses, Christ and Gandhi as foundational for his belief in self-sacrifice and nonviolence (García, 54 & 66). Furthermore, Chavez and the UFW are famous for the utilization of the image of the Virgen de la Guadalupe during the marches; Chavez also mentions that the Star of David was featured (García, 97).

What about Islamic representation? Again, historical work on American Muslims tends to be a very recent field of study. However, a tragic moment in UFW history also served as an example of how Chavez was able to bring people from all walks of life to the movement, highlighting the religious roots of the diverse mix of farmworkers.

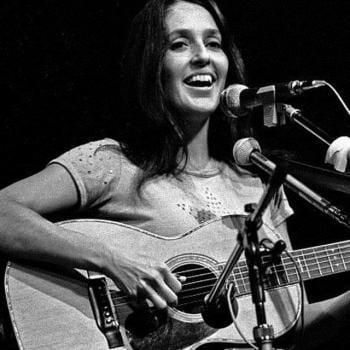

A Muslim organizer of Yemeni descent, Nagi Daifallah (age 24), was beaten to death during the 1973 Grape Strike. His murderer was never brought to justice (this podcast does an excellent job telling Daifallah’s story and the greater story of Yemeni migration to the U.S.). A fellow farmworker Juan De La Cruz was murdered a couple of days later (I have researched Joan Baez’s role at his eulogy and hopefully will see the light of day shortly). These deaths forced a change in policies and led to a historical shift in the bargaining power of farm workers.

What stands out about Daifallah’s death is the Christian/Muslim ceremony at his memorial. There was a silent vigil as the mourners walked for miles toward the airport since the UFW would send his casket back to Yemen to honor him; they also provided for Daifallah’s father monetarily until his death because of his son’s sacrifice (García, 132). Daifallah was recently honored with a mural memorial, and is now seen as a pioneer in US Muslim activism, referenced in the recent travel bans as an inspiration to get people involved to speak out against injustice.

One of the key components of religion is memorializing martyrs. We have seen that with Daifallah’s memory. However, the first recorded death among the UFW was a young Jewish student, Nan Freeman (age 18). Chavez would write the following about Freeman: “To us, Nan Freeman is Kadosha in the Hebrew tradition, a holy person to be honored and remembered for as long as farm workers struggle for justice.” One of the highlights of Chavez’s legacy is the way he weaved religious beliefs with struggles for justice in a way that memorialized the martyrs for farmworkers in overt religious symbolism (see images below).

Jewish-Christian-Muslim: all martyrs for the rights and dignity of the farmworker.

In closing, an important trend in recent Christian History is the ecumenical movement. We have inherited its legacy. A crucial part of it, what I think is its biggest success, is the constructive dialogue between the 3 monotheistic faiths. Unfortunately, it took the demonic violence in the recent past to actually bring the practitioners of these 3 faiths finally together at the table of fellowship. Even after the mid-twentieth century, we have had our fair share of politically violent moments. Empathy, tolerance, and prayer were constructive responses to these past tragedies. The same should apply today.

Why does it often take terrible spectacles of violence to get people to finally sit down and talk? My prayer, in our own current moment of crisis, is to see more constructive opportunities of the type of dialogue that great figures in American history like King, Heschel, and Chavez can teach this generation.