Good news; but if you ask me what it is, I know not;

Good news; but if you ask me what it is, I know not;

It is a track of feet in the snow,

It is a lantern showing a path,

It is a door set open.

–G. K. Chesterton

In the company of animals — inside their door, upon their foot-worn floor, in the light of the lantern hung from their rafter, and in their care, Christ is born. Luke mentions none of them by name but describes the Child’s birth in a stable, the infant laid in a manger – a feeding trough for working animals – because there was no other room.

Legend quickly named these animals that served the inn and its guests, providing food and transport: cow and donkey, chickens and geese, doves in the rafters.

Legend quickly named these animals that served the inn and its guests, providing food and transport: cow and donkey, chickens and geese, doves in the rafters.

Luke’s own pen gave us the heavenly host caroling shepherds over Bethlehem fields, who then come to see the Child. And we have in our minds that they brought with them the sheep that could not be left behind, orphaned lambs, the injured and ill. No crèche would be complete without them, nor are there many carols that omit them.

My Advent calendar on the 21st featured a child reverently carrying a figure of a sheep to church, to add to the altar crèche. In pageants everywhere small children dress as little lambs to sing Away in the Manger to the Child John’s gospel calls the Lamb of God. Our carols speak of these animals providing the Child with warmth through their breath, clothing through their wool and feathers, lullabies, milk – and love.

This is more than sentimentality. The Apostle Paul writes that the whole creation is groaning in travail, waiting for the redemption of the world. Job, in his suffering, surrounded by friends who could not understand him, said:

Ask the animals, and they will teach you; the birds of the air, and they will tell you;

ask the plants of the earth, and they will teach you;

and the fish of the sea will declare to you.

Who among all these does not know that . . . in the hand of the Lord . . . .

is the life of every living thing and the breath of every human being?

With him are strength and wisdom; the deceived and the deceiver are his.

He leads counselors away stripped, and makes fools of judges.

He leads priests away stripped, and overthrows the mighty.

He pours contempt on princes, and looses the belt of the strong.

He uncovers the deeps out of darkness, and brings deep darkness to light.

He makes nations great, then destroys them;

he enlarges nations, then leads them away.

He strips understanding from the leaders of the earth,

and makes them wander in a pathless waste. (Job 12: 7-10, 16 – 24)

Indeed, Mary has famously sung about God in this way early in her pregnancy.

Indeed, Mary has famously sung about God in this way early in her pregnancy.

What is happening at Christmas, then, is not just for humans. Nor is it a party for a sweet baby at which everyone basks in pure joy. In this very moment there is deprivation and desperation. Mary, like one of these overworked creatures, will bear her child in conditions more rugged than she could have imagined. In her labor, she and her child become a shiver in the fabric of time, a groan of deep darkness riven by light. What is hidden is revealed, and timelessness enters a mortal moment that is replete with danger.

The wisdom that comprehends this best, the wisdom that ‘makes room’ for this knowledge in itself, is not the collected human wisdom of the educated, the mighty, the secure, who are Job’s comforters when it comes to suffering. Those who can see this birth, hidden as it is by being ‘out of sight’, are creatures who do not have power over their own lives – animals: fragile, hungry, hard-worked, and aware of depths of hopelessness and hope that go far beyond human words. And the people who live with them in their harsh conditions – shepherds – are, in God’s esteem, spiritually more in tune with the divine than the rest of us, people of towns and houses, cultures, customs beyond the ovine and bovine.

It has always been this connection, between sheep and humans who care for them, that has held special favor in God’s sight. Abel, keeper of sheep, the son whose offering pleased God the most; Jacob, the trickster, redeemed in part by his skill at husbandry among the herds; David, the Chosen King who was a shepherd boy; Jesus, who calls himself the Good Shepherd and holds up the lost sheep found as his token of Good Shepherding – these incidents are part of a repeated theme.

There is a divine connection in people who live among herds of other creatures and in service to them, a connection lost to other people, people of cities and towns. And in testimony of this, Christmas is set in a little Eden – the stable – where the Child is born into a small gathering representative of creation’s story. Home – for the Child, and also for all of us over the centuries – will always be this setting.

There is a joy we often miss in this, a humor that ripples through Christmas bleakness, in the story of these shepherds. Angels sing Praises to a company of rough shepherds – the cowboys of the Bible – in contrast to the temples where people sing practiced praises to God. And the guffaws of God must rumble through Christmas night.

There is also a protection here. The soldiers of Herod, soon to arrive upon the scene seeking to destroy the Child, will not check the barns until they have exhausted every home and inn. Under the cloak of creatureliness the Child and Mary and Joseph will make good their escape, following the tracks of sheep and the paths of shepherds, led by an angel to the open door of the borderlands.

There is also a protection here. The soldiers of Herod, soon to arrive upon the scene seeking to destroy the Child, will not check the barns until they have exhausted every home and inn. Under the cloak of creatureliness the Child and Mary and Joseph will make good their escape, following the tracks of sheep and the paths of shepherds, led by an angel to the open door of the borderlands.

No wonder there are legends of these hours as a magical time when the animals could speak. Shakespeare, in Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 1, says of Christmas night: The bird of dawning singeth all night long. . . . no planets strike. No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm, So hallowed and so gracious is that time.)

Thomas Hardy writes of this in his poem, The Oxen:

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so. ___________________________________________________________ Illustrations:

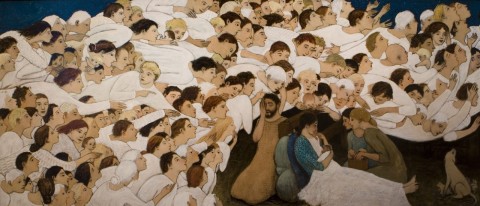

1. Nativity, by Brian Kershisnik, depicts a surrounding of sheep/people/angels, all becoming one creature in a mystical Christmas. Note the dog with puppies in lower right. Image from Utah Museum of Fine Arts website.

2. Nativity, Unknown Master, Master of Salzburg. c. 1400. Image: Web Gallery of Art.

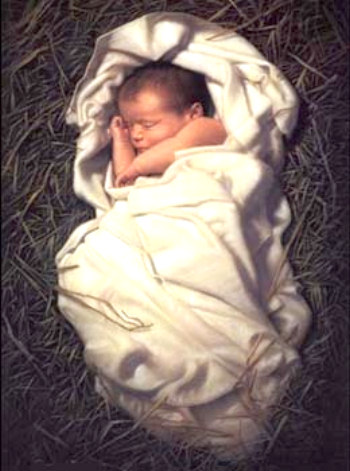

4. Baby Jesus in Hay. image, Christmas Image Gallery.

5. Flight into Egypt, by Albrecht Durer, Dresden, Germany, 1494 Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

6. The Census at Bethlehem, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1566. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

7. The Adoration of the Shepherds, detail, by Caravaggio, 1609. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.