Texans are ringing in the New Year by wearing their guns in public places, a newly enacted right they have awarded to themselves. Last I knew, Texas was still Bible Belt country, but Jesus’ urging that we love our enemies and do good to those who spitefully use us seems not to be in vogue these days, and at least in Texas, is not a kind of human respect found in the law.

Texans are ringing in the New Year by wearing their guns in public places, a newly enacted right they have awarded to themselves. Last I knew, Texas was still Bible Belt country, but Jesus’ urging that we love our enemies and do good to those who spitefully use us seems not to be in vogue these days, and at least in Texas, is not a kind of human respect found in the law.

Up north, New Yorker Donald Trump, front runner for the GOP nomination for President, has declared Senator John McCain to be no hero. Long venerated for his survival through many years of torture in a tiger cage in Vietnam, McCain had been considered a national hero, but Trump insists that heroes have to do some marvelous good for the rest of us, not just suffer. Trump even says that McCain was a loser. And heroes have to be winners. Where does this leave Jesus, then?

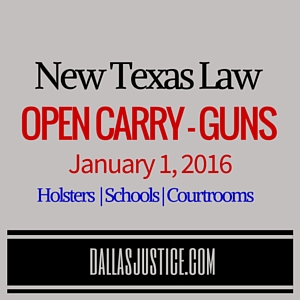

Adam MacKay’s new movie, The Big Short, unmasks the widespread corruption and fraudulence of the American banking industry in the 1990s, that led to the economic recession of 2008. Banks, the mortgage industry, and the watchdog groups supposed to guard our interests, and even the Wall Street Journal, cooperated in schemes each of them knew was wrong, and in the wake of the destruction they caused, walked away unscathed.

Only one banker (an Arab immigrant) went to jail. Most used their bailout money to give themselves big bonuses, not to make r estitution to people who lost homes, jobs, pensions, IRA savings. At the end of the film, MacKay warns the schemes are all starting up again, packaged in new terms. So does Jesus’ overturning of the money-changers tables mean nothing to us now? And what about his many stories, urging fair pay for everyone, not measuring work but need? What about his generosity to the poor and sick, widows and orphans? To prodigals? To strangers?

estitution to people who lost homes, jobs, pensions, IRA savings. At the end of the film, MacKay warns the schemes are all starting up again, packaged in new terms. So does Jesus’ overturning of the money-changers tables mean nothing to us now? And what about his many stories, urging fair pay for everyone, not measuring work but need? What about his generosity to the poor and sick, widows and orphans? To prodigals? To strangers?

NPR interviewed the elegant essayist Larissa MacFarquhar, author of Strangers Drowning: Voyagers to the Brink of Moral Extremity, a book that takes a long look at the lives of those who devote themselves to doing good, in a world that regards the virtuous with wary suspicion. And here I am stunned: who knew that the world regards great virtue with suspicion?

MacFarquar writes to explore this question: should we admire people like these, and celebrate their generosity and maybe even seek to emulate their saintliness? Or are we right in finding them incredibly annoying, and in wondering if their need to give so much and so often is really just the product of a lot of messed-up psychology?

MacFarquhar said, in her NPR interview, that the only act of noble self-sacrifice given widespread respect in today’s America is fighting war. And this was no virtue to Jesus, who said, Those who live by the sword will die by the sword, and who dedicated his life and his death to works of peace and goodwill. The virtuous, in today’s world, according to MacFarquhar, have become a conundrum. And how do we know the virtuous? Her definition, summed up in a book review in The Guardian:

To very virtuous people, human suffering is not a background hum, it is a piercing alarm that calls them to duty. How each responds to that call will differ. One might quit her job, move to a country in the middle of a violent revolution, and found a women’s clinic. Another might decide that he should adopt troubled children, and end up adopting 20. Another might pursue a lucrative career in order to have more money to donate to charity – if not 100% of her income, then 85%. In each case, these people subordinate everyday desires to the more important business of making the world a better place. (David Wolf, The Guardian).

Who is Jesus, to us, then? Is he incredibly annoying, is he psychologically messed up? Should we admire him? Doesn’t Jesus urge us to consider what MacFarquhar calls moral extremity, as the norm for human behavior?

Who is Jesus, to us, then? Is he incredibly annoying, is he psychologically messed up? Should we admire him? Doesn’t Jesus urge us to consider what MacFarquhar calls moral extremity, as the norm for human behavior?

If our attitude toward virtue far beyond our own (certainly far beyond mine!) is to suspect it is a form of mental illness, no wonder many concentrate instead on Jesus as a miracle man, venerating his storied birth, clinging to hope he will fly in and fix every situation, and resting upon his promised eternal life, rather than striving to follow in his footsteps.

Paul Farmer, the Harvard Medical Professor who spends most of his life in the mountains of Haiti bringing health care to desperately poor and ill people, has been a hero to me for years. Mother Teresa, her arms wrapped around dying strangers in the streets of Calcutta. The churchwoman I know, a veterinarian, who travels a few weeks a year to poor countries, to treat their ill and desperately needed goats, chickens, pigs, and the occasional cow? If these are the people who annoy us, is Jesus being shown the cultural door?

God help us, in 2016.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Texas Gun Law Poster.

2. Donald Trump, Wikipedia page photo.

3. The Big Short movie poster.

4. Strangers Drowning book cover.

5. Paul Farmer in Haiti, treating a mother and child, 2003. Wikipedia page photo.

6. Mother Teresa, accepting the Nobel Peace Prize. Wikipedia page photo.