“. . . . once again they broke the Love Laws. That lay down who should be loved. And how.

“. . . . once again they broke the Love Laws. That lay down who should be loved. And how.

And how much.”

― Arundhati Roy in

It’s a week before his death, and John has written that Mary, whom we already know loved Jesus intensely, is immersed in an ocean of feelings about his approaching doom. Jesus has come to her house for dinner, an intimate meal with her, her sister Martha and her brother Lazarus. Mary brings out a bottle of expensive, perfumed oil, pours it over Jesus feet, massages them lovingly, then gently caresses his skin with her long hair.

Jesus does not murmur in surprise. Neither is he embarrassed. He accepts this intimacy, this tenderness, with the pleasure it is meant to give. Nor do any of the others register surprise. The comfort they all feel with her touching him is evidence she has touched him before, that she and he are intimate beyond the rest.

In fact, John has written about other times Jesus visited this house, and each time there was an intimacy with Mary that set her apart from the rest. There was the time he brought all his disciples there, so we know the house was large, they all fit comfortably in the sitting room. Mary sat at his feet, in the circle of the men, and Martha, who wanted to bring them all food, fussed to Jesus that Mary should be in the kitchen with her. And Jesus defended Mary. She has chosen the good portion, and it is not to be taken away from her, he said. The good portion: being close to him; close enough to touch him. And being touched by him, in her mind, her heart. At least this. And maybe more.

And then Lazarus, her brother, fell terribly ill. John writes that Martha and Mary nursed him as best they could, and sent for Jesus. But Jesus delayed setting out, and before he arrived, Lazarus died. Mary was beside herself with grief, and went a day’s journey on the road, meeting Jesus there. In anguish, in a tumult of tears, she accused him: if only, if only, if only, you had come, he would not have died!

And then Lazarus, her brother, fell terribly ill. John writes that Martha and Mary nursed him as best they could, and sent for Jesus. But Jesus delayed setting out, and before he arrived, Lazarus died. Mary was beside herself with grief, and went a day’s journey on the road, meeting Jesus there. In anguish, in a tumult of tears, she accused him: if only, if only, if only, you had come, he would not have died!

Her sobbing affected him so that he also cried. Jesus wept. It stands as a verse, alone. Jesus wept. His heart awakened to her, and broke for her. In the strength of his own tears, which were brought forth by hers, in his grief that he had so disappointed her, he brought Lazarus out of his grave – for her.

And now they are all together again, eating Martha’s good cooking. Judas, it turns out, is also there that evening. And according to John he complains that the perfumed oil is too expensive, and the money should not have been so lavishly spent. Is he jealous of Mary’s place in Jesus’ affections? John accuses him of being a thief, but Jesus does not say that. He defends Mary, saying she bought this oil for his death. And that he will not be with them for long. He does always leap to defend Mary.

The story shifts, for John says a crowd arrived to see both Jesus and Lazarus, word having gotten out that Jesus was there. And John tells us the soldiers planned to kill Lazarus, too, because, like Jesus, his being alive was too powerful for them.

Matthew and Luke also remember Mary’s caresses, writing of the perfumed oil being poured out on Jesus’ hair and neck, and then the caressing by a nameless and deeply tender woman, their gospels say. They put this moment at the Last Supper, which was also held in Martha and Mary’s house. So it isn’t odd to conclude the woman was Mary. Matthew and Luke write that Jesus defended her to Judas by saying ‘she has done a beautiful thing for me, and this story should be told endlessly, in memory of her.’

Matthew and Luke also remember Mary’s caresses, writing of the perfumed oil being poured out on Jesus’ hair and neck, and then the caressing by a nameless and deeply tender woman, their gospels say. They put this moment at the Last Supper, which was also held in Martha and Mary’s house. So it isn’t odd to conclude the woman was Mary. Matthew and Luke write that Jesus defended her to Judas by saying ‘she has done a beautiful thing for me, and this story should be told endlessly, in memory of her.’

Nikos Kazantzakis, Greek literary lion, wrote in The Last Temptation of Christ, that on the cross the longing of Jesus’ heart was for Mary, and also for Mary Magdalene, that he spent his suffering hours passionately imagining the life he might have had with each of them, and then at the last knew that it was this bliss in life he was giving up in his death.

The most important work on this story has been written by Catholic theologian Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, in the book In Memory of Her. Fiorenza’s writings have changed the perspective of New Testament scholarship in regard to women, and have led to extensive re-examination of Jesus’ life, in canonical and non-canonical gospels. Much new material has been discovered and some old material about Jesus’ physicality that had been suppressed in favor of a non-sexual image of Jesus has been recovered. That Jesus was not sexual is official doctrine in Fiorenza’s own church, but all Christians are complicit in fostering this image.

In another week, as Holy Week begins, we will read of Judas betraying Jesus with a kiss. Yet perhaps we betray Jesus more by insisting on this pretense: that Jesus refrained from intimacy of the body and was only a friend in spirit to Mary and to Magdalene. We pretend that the man who gave the first cup of eternal life to a woman he knew had had five ‘husbands’, the man who protected a woman from being stoned for adultery, did not really experience desire, and did not himself indulge in it. In doing this, we forget the one moment in his life that Jesus named as beautiful, and the blessing he gave to Mary’s caresses, as part of . . .

In another week, as Holy Week begins, we will read of Judas betraying Jesus with a kiss. Yet perhaps we betray Jesus more by insisting on this pretense: that Jesus refrained from intimacy of the body and was only a friend in spirit to Mary and to Magdalene. We pretend that the man who gave the first cup of eternal life to a woman he knew had had five ‘husbands’, the man who protected a woman from being stoned for adultery, did not really experience desire, and did not himself indulge in it. In doing this, we forget the one moment in his life that Jesus named as beautiful, and the blessing he gave to Mary’s caresses, as part of . . .

. . . . the luminous sprawl of gifts,

the hospitality of the Lord, and my

inadequate answers as I row my beautiful, temporary body

through this water-lily world.

— Mary Oliver, in Six Recognitions of the Lord

____________________________________________

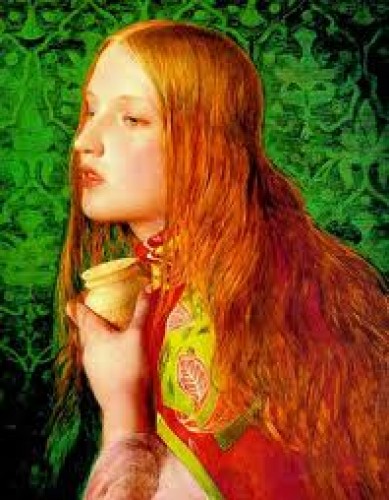

Illustrations: (over the centuries, many have thought the unnamed woman was Mary Magdalene, and much of the art of this event is named ‘Magdalene’. The iconographic tradition is to paint the woman with a jar (the perfumed oil) in her hands, and also to paint her red-headed, an attribute of passionate emotion ascribed to Magdalene in the Middle Ages.)

1. Mary Magdalene, Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys. . ca. 1860,

Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition..

2. Saint Mary Magdalene Penitent. 1615 Fetti, Domenico. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christina Tradition.

3. Detail from The Feast of Simon the Pharisee, Peter Paul Rubens,

Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Mary Magdalene, c. 1524. Antonio Lombardo. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.