The uses of sorrow – as Jesus unfolds them – are many, and powerful. Sorrow becomes a fertile ground in which broken hearts become miracles of green life. But all of this requires eyes and minds attentive to the life that grows from sorrow. And this attentiveness requires looking deeply into sorrow, without fear and without turning away.

The uses of sorrow – as Jesus unfolds them – are many, and powerful. Sorrow becomes a fertile ground in which broken hearts become miracles of green life. But all of this requires eyes and minds attentive to the life that grows from sorrow. And this attentiveness requires looking deeply into sorrow, without fear and without turning away.

America may be the hardest place of all in which to look into sorrow. All of us descend from people who came here to escape sorrows, to find refuge from them, people whose gospel was leaving tears behind and moving into a land of milk and honey, a new Eden, a new identity. Leaving the rotted past is the reason for coming to America. People are still coming, for that reason.

Our Declaration of Independence secures us the right to pursue happiness, and we have evolved a grief-phobic culture, in which all the pictures in the family albums show us smiling. But the past is with us. We are haunted by its shadows. And, in that we are still human, the unspeakable acts of the past continue among us here.

Holy Week is not about pursuing happiness. And that may be why so many Christians, in America, avoid it. Holy Week is not about healing, if healing means that life will be like it was. Holy Week is about surviving with a broken heart, and cherishing that brokenness, so that your life is transformed by it.

Maundy Thursday is the story of Jesus keeping the Jewish Passover with his friends. Passover is a festival that seeks the way to the future in revisiting the past. David Brooks, who is Jewish, wrote last week in an op-ed in The New York Times, Happiness wants you to think about maximizing your benefits. Difficulty and suffering sends you on a different course. . . . people who endure suffering are taken beneath the routines of life and find they are not who they believed themselves to be. Try as they might, they just can’t tell themselves to stop feeling pain, or to stop missing the one who has died or gone.

Maundy Thursday is the story of Jesus keeping the Jewish Passover with his friends. Passover is a festival that seeks the way to the future in revisiting the past. David Brooks, who is Jewish, wrote last week in an op-ed in The New York Times, Happiness wants you to think about maximizing your benefits. Difficulty and suffering sends you on a different course. . . . people who endure suffering are taken beneath the routines of life and find they are not who they believed themselves to be. Try as they might, they just can’t tell themselves to stop feeling pain, or to stop missing the one who has died or gone.

People in this circumstance often have the sense that they are swept up in some larger providence . . . . (and) begin to feel a call. They are not masters of the situation, but neither are they helpless. . . . . Instead of recoiling from the sorts of loving commitments that almost always involve suffering, they throw themselves more deeply into them.

The suffering involved in their tasks becomes a fearful gift . . . .

The suffering involved in their tasks becomes a fearful gift . . . .

In Matthew’s account, Jesus spends Holy Week teaching about the uses of sorrow. In the temple, after driving out the money changers, who are supporting the industry of happiness – you come to the temple, you buy an animal and sacrifice it, and you go away happy to have gotten the blessing you sought – Jesus launches into teaching parables of disappointment and even of suffering violence. As he leaves the temple he cries out a Woe for Jerusalem, the city which does not understand peace, and will not allow him to mother it. And he predicts the devastation of Jerusalem to come.

In the Upper Room, Jesus keeps the Passover Seder, a night and a meal for remembering the story of the Exodus, the hideous suffering of slavery, and the cost of deliverance: courage and fear, wandering and trust, living in wilderness and holding onto the hope of home. Jesus dedicates the ritual bread of freedom as his own body, and the cup of Elijah’s promised return as the promise of his own presence in a covenant of forgiveness.

And so his name, Beloved – given to him at his baptism in the Jordan – is now their name, and it has new meaning: not fairytale happiness, but a call to commitment, a call to to the very vulnerability that caused his suffering . As they move on, to the Garden, the cross, they remember this.

. . . . everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires

and the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

(Mary Oliver, from ‘In Blackwater Woods’)

Beloved. In the unyielding ache of their last meal they become each other’s beloved, bound by tears shared and remembered, and by their terrible loss, and by things they’d left undone, when he was theirs.

___________________________________________________________

Illustrations

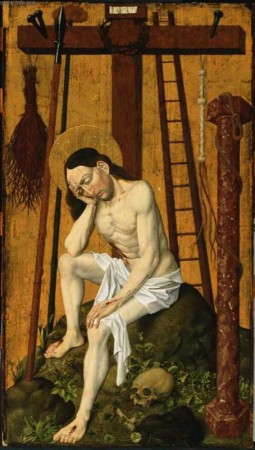

1. Christ as the Man of Sorrows. Alsatian. 1470. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. The Feast of Passover. Bouts, Dieric. 1464. St. Peter’s Church, Leuven, Belgium. Vanderbilt Divinity School, Art in the Christian Tradition

3. Dragon. Washington National Cathedral window. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

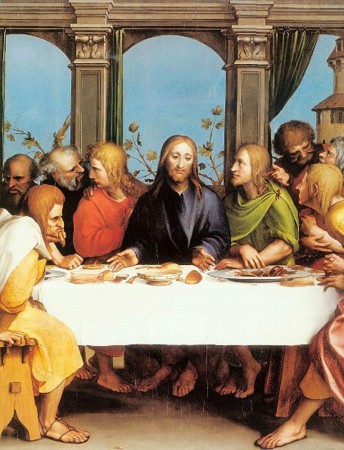

4. The Last Supper. Holbein, Hans. 1524, Altarpiece, Basel, Switzerland. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

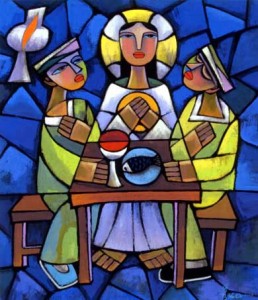

5. Supper at Emmaus. He Qi 2001. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.