Now the cycle of Easter stories circles back upon itself. The circle does not return to Easter dawn, the circle is wider than that. The circle reaches round and back to the Last Supper, to the moment when Jesus’ agony begins.

Now the cycle of Easter stories circles back upon itself. The circle does not return to Easter dawn, the circle is wider than that. The circle reaches round and back to the Last Supper, to the moment when Jesus’ agony begins.

John tells the story with interlacing love and pain. Jesus’ ultimate instruction to his disciples, the final intimate step in the arts of love in which he has been leading them, is footwashing. He wordlessly prepares himself to wash their feet. They, in astonishment, protest. And he tells them this is the only way to enter Heaven, and both giving and receiving such loving care is to be their model of loving life. I have set you an example, he says, and in his familiar way of turning the world upside down, he explains that they now need to do this in order not to seem to be greater than he is.

And then he tells them that one of them, who has been so embraced and served by him, will betray him, and he hands that solemn bit of bread to Judas. Judas departs, to become an example of something other than tender care.

They do not understand, John writes. Nor have any of us, since then, really understood. The story becomes a form of temptation, pulling us away from Jesus’ expressed teaching about loving care, and toward our deep desire to find someone to blame, a scapegoat to take the burden of our rage and pain when things go wrong. We are universally familiar with Judas as the villain, the one everyone may reject. And far less interested in having our feet washed by one another. We are far more concerned with hiding our own dirtiness and exposing Judas’ dirty soul.

They do not understand, John writes. Nor have any of us, since then, really understood. The story becomes a form of temptation, pulling us away from Jesus’ expressed teaching about loving care, and toward our deep desire to find someone to blame, a scapegoat to take the burden of our rage and pain when things go wrong. We are universally familiar with Judas as the villain, the one everyone may reject. And far less interested in having our feet washed by one another. We are far more concerned with hiding our own dirtiness and exposing Judas’ dirty soul.

It would all seem academic, had we not been living the story here in Boston this past week. The Marathon is our most sacramental public holiday, replete with tender traditions like the Hoyts, a father who has, for nearly 40 years, pushed his severely handicapped and wheelchair bound son the entire 26.2 miles. He began when the boy was young, saying it was the only athletic thing he could do with his son. And he has never stopped. There are hundreds of stories like this, and we revel in them. Each is a foot-washing for the soul, as well as a devotion of the body.

The bombs hit us in our collective soul, and they hit the bodies of nearly 200 who are dead, maimed, and injured. Our public image of the good that is among us was crucified.

The bombs hit us in our collective soul, and they hit the bodies of nearly 200 who are dead, maimed, and injured. Our public image of the good that is among us was crucified.

The week has been spent looking for the betrayers. The tension has been immense. Over and over the stories have been told of those who tore down metal barriers to get to the injured, those who put out fires in people’s clothing with their bare hands, strangers who took off their belts and shirts to make tourniquets, gave words of encouragement and reassurance that made a world of difference. These are our footwashing servant tales, and we draw Jesus’ strength from them.

The focus on catching the perpetrators has also been immense. They are now captured, but our anger still rolls. How could they, who have lived among us and become part of us, have done this? Who put them up to it? Is it because they are immigrants? Moslems? Chechens?

Some questions Christians might ask are: How did they become possessed by hatred, and were their souls turned entirely to evil? Who were they serving in this act – for whose love did they do it? To some degree, the way we view Judas defines how we see these two Chechen-American brothers, one now dead, one still alive, who betrayed us so.

In the Scripture, John adds cryptic details: first, that Jesus prepared to wash their feet ‘knowing that God had given all things into his hands.’ All things include Judas. Second, that he urges Judas to ‘Do what you are going to do quickly.’

English theologian Graeme Davidson* reminds us that Jesus brings into the world grace to redeem all who have fallen short of the glory of God, and Judas is part of all. Davidson postulates a form of service, to the glory of God, in Judas’ act.

English theologian Graeme Davidson* reminds us that Jesus brings into the world grace to redeem all who have fallen short of the glory of God, and Judas is part of all. Davidson postulates a form of service, to the glory of God, in Judas’ act.

But John’s comments, that Satan entered Judas’ soul, are quite condemnatory, more than the other gospel tellings. And yet, according to John, all that happens is at Jesus’ bidding. Jesus deliberately hands the bit of bread to Judas. And he says as Judas leaves, Now the Son of Man has been glorified, and God has been glorified in him.

Jorge Luis Borges**, the acclaimed Argentinian writer, wrote a small book about Judas in the 1940s, finding three possible, honorable roles for Judas in Christ’s drama: that Judas becomes a reflection of Jesus, balancing his divine sacrifice with the sacrifice of Judas’ humanity, much as on a seesaw one must sink down in order for the other to rise up; that Judas engages in an extravagant asceticism, renouncing all goodness and the Kingdom, to demonstrate that the felicity of Jesus was satisfaction enough for him; and finally, that Judas fulfills the prophecy of Isaiah 53, that the Messiah will be despised among people, and in this Judas completes Jesus.

All of these rationales are hard for me to accept. I have imbibed deeply the notion of Judas as villainous, and the notion that there are villains in the world. Yet there is a challenge of understanding that is clearly echoed in Jesus’ words to the others after Judas departs. Jesus tells the others that the world will know they belong to him by their love.

Davidson and Borges put that challenge more philosophically: that we must stop seeing Jesus as engaged in a cosmic battle against evil, and begin to grasp that evil and good are intertwined in the story of the glory of God in this world. We need to see Jesus as embracing all the world. Not just some in it, but all. And, as Jesus has shown us in every parable and deed, our understanding of what is good and who is evil is very often wrong. Caesar, Pilate and Herod agreed that Jesus was an evildoer. And that they could stop him. They could not have been more wrong.

Faced now with the stark reality of a 19 year old Chechen immigrant, who has committed horrible crimes against families and children and the soul of a wonderful city, a man who moved to a humble, working class part of Cambridge MA when he was 7 and became an American citizen last fall, I am compelled by Jesus’ admonishments to find a place for him at the human table. This is as necessary a duty for me, as it is for the doctors to save his life, without regard to how he has lived it.

Faced now with the stark reality of a 19 year old Chechen immigrant, who has committed horrible crimes against families and children and the soul of a wonderful city, a man who moved to a humble, working class part of Cambridge MA when he was 7 and became an American citizen last fall, I am compelled by Jesus’ admonishments to find a place for him at the human table. This is as necessary a duty for me, as it is for the doctors to save his life, without regard to how he has lived it.

Jesus came among us as one who serves and Judas was one whom he served. As one who tells this tale, it is important that I not omit there is one who belongs in it who did something most of us consider terribly evil. And that he, too, is part of the story of how God is glorified. Even Judas is part of the washed, part of the story of Easter.

____________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Veronese, Footwashing, National Gallery, Prague, Czech Republic, 1580. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Footwashing, Stone Relief, Saint-Lazare Cathedral, Autun, France, 1130. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Wanted Poster, images of Marathon bombers distributed by FBI. April 17, 2013

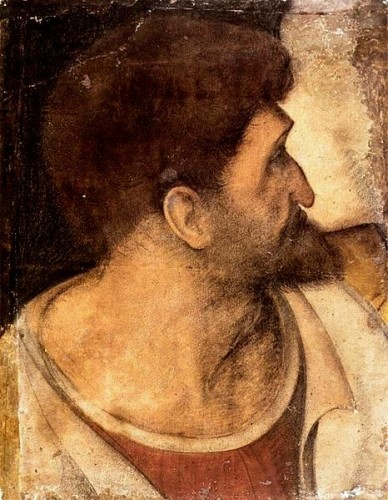

4. Judas. Boltraffio, after Leonardo. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. Sidewalk Art , Copley Square, Boston, near Marathon bombing site. Christian Science Monitor and present on many blogs.

Citations:

*. Davidson, Graeme, in TheologicalEditions.com, The Case for Judas Iscariot, 2001. **. Borges, Jorge Luis, in Three Versions of Judas, in Artificios, 1944.