We are all called to be mothers of God – for God is always waiting to be born. – Meister Eckhart, 13th c. German mystic

We are all called to be mothers of God – for God is always waiting to be born. – Meister Eckhart, 13th c. German mystic

It is only Luke who includes the conversation between the Archangel Gabriel and Mary, a conversation of questions, explanations, and then consent to bear a Child who will change the world. According to Matthew, the issue at hand, the how-shall-this-happen question that follows the Child to this day, was Joseph’s issue, and it was to Joseph that the angel spoke, it was Joseph’s questions that the angel answered, and it was Joseph’s consent to this pregnancy that Matthew remembers.

The other gospels do not deal with Jesus’ birth. Mark manifests his divinity at his baptism. John threads it into the cosmos, before the world began.But according to Luke, Mary is not a passive vessel, she is spiritually integral to the creation of this child. The angel acknowledges her as full of grace before their conversation, and before her consent, and before she becomes pregnant. Luke then tells us of her journey and her speech, both made in response to her pregnancy, and in response to her conversation with the angel. Both her journey and her speech are prophetic; passionate; determined; full of the grace the angel had named as particular to her, in the first moment of their meeting.

The interactions between angels and women in biblical literature are rare, and indirect. Angels converse with Abraham, asking about Sarah, and relaying a message to her, through him, about a child. They are at last answering her prayer, long years after her beseeching had begun. And though they make the point to Abraham that it is her prayer, not his, that is being answered, they do not converse with her. In similar fashion the prayer for survival for herself and her son prayed by the widow of Zarephath, whose hope is almost gone, is answered indirectly by an angel who sends Elijah to her as emissary. Later, Elijah intercedes for a childless woman, as the prophet Eli also did for Hannah, whose passionate prayers drew his attention. Beyond these four, the concerns of women attract no noted divine attention.

The interactions between angels and women in biblical literature are rare, and indirect. Angels converse with Abraham, asking about Sarah, and relaying a message to her, through him, about a child. They are at last answering her prayer, long years after her beseeching had begun. And though they make the point to Abraham that it is her prayer, not his, that is being answered, they do not converse with her. In similar fashion the prayer for survival for herself and her son prayed by the widow of Zarephath, whose hope is almost gone, is answered indirectly by an angel who sends Elijah to her as emissary. Later, Elijah intercedes for a childless woman, as the prophet Eli also did for Hannah, whose passionate prayers drew his attention. Beyond these four, the concerns of women attract no noted divine attention.

Until Mary. Luke, raised in Greece and educated in Greek culture, knew the iconography for divine heroes that ran through the related Greek. Celtic, and Hindu cultures, knew that the mothers of divine heroes all experienced a ‘triple birth’, which is to say, three possible fathers, one mystical, one a magical creature, and one human. As Luke tells the story, Mary’s pregnancy involved all these: the Spirit of God, an archangel, and Joseph. As well, divine heroes in these cultures are often born among animals, and poor shepherds or fishermen offer the endangered mother shelter. Mary’s baby had these blessings and protections, too.

But Luke adds something more: her grace-filled spirit, which the angel honors in greeting, and which she manifests in her vision for the child. Where an ordinary woman would dream of a child who would elevate her in this world, Mary dreams of a child who will liberate all the lowly. Where it might be commonplace to dream of a child whose glory would extend to Mom, Mary dreams of a child who will fill all the hungry with good things. Where any mother might dream of a child who will grow up and be Somebody, Mary imagines a child who will knock all the Somebodies of this world off their thrones, who will scatter them in their false imaginations and raise the lowly in his new, true world.

In Greek and Celtic legends, the women whose sons become divine heroes are silent in their encounters with magical creatures, and even their husbands. I, who have always been articulate, am often taciturn before authorities, doctors, even technicians. Before an archangel, I imagine myself speechless. Obedient for lack of the ability to demur. But Mary opens a discussion, and turns the angel from an authoritarian proclaimer into a small-print explainer.

Her grace, then, is in part her strong center, her sense of who she is – her soul, which sings and sighs but also signals and sounds the depths of all that reaches her. Even God. Whom, she says, she is enlarging in her soul.

In her soul. Not, as is mostly assumed, in her womb. My soul enlarges God and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, she sings, and from this day forth all generations will call me blessed. It is she herself in whom God is magnified, a concept the Orthodox, more deeply aware of the tradition in which Luke is writing, have grasped in their Mary Theotokos elevation of her.

Western Christians, conflicted by unyielding traditions of femininity as spiritually less than masculinity, of the purity and impurity of flesh, and of wisdom as exclusively male, find Mary enigmatic. The assumption of her youthfulness, her teen or preteen age, is fundamental in the west, though neither Luke nor Matthew every mention her age. Most of all in the West, though we do not talk about it, we are unable to imagine her as free from fear. Her boldness at Cana startles us, and we have a canon of explanations for her courage there.

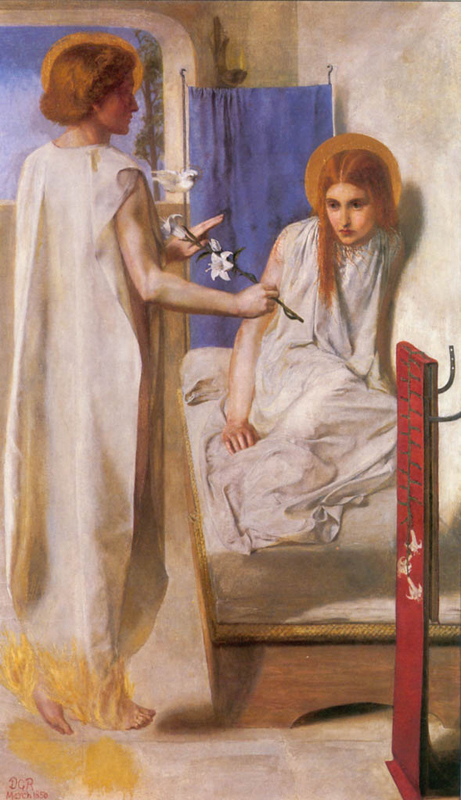

But from the first, Luke presents her as free from fear. In the presence of an angel, on her solo journey to the home of Zechariah, a temple priest, in her consideration of the power and the future of the world, she is fearless. In a stable in a strange city, in labor and surrounded by strangers post-partum, she is fearless. Fleeing from an army hunting for her Child, she is fearless, as she is in Egypt, for Luke tells us the Child flourished and was full of grace and favor. She carries her Child through centuries still, and everywhere she goes, people honor the fearlessness in her. ____________________________________________________________ Illustrations:

1. Annunciation, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 1849-50. Tate, London. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Detail, Annunciation, by Fra Angelico. 1418. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Archangel, by Cosme Tura. 1469. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Annunciation by Esmond Lyons. Contemporary. Google Images.

5. Annunciation by Esmond Lyons. Contemporary. Google Images.

6. Modern Mary by Esmond Lyons. Contemporary. Google Images.