After John was arrested. Mark adds a sinister dimension to the calling of disciples – it takes place not in the halcyon days by the Jordan, but after John has been shut down, silenced, taken into custody from which he will never emerge to speak again.

After John was arrested. Mark adds a sinister dimension to the calling of disciples – it takes place not in the halcyon days by the Jordan, but after John has been shut down, silenced, taken into custody from which he will never emerge to speak again.

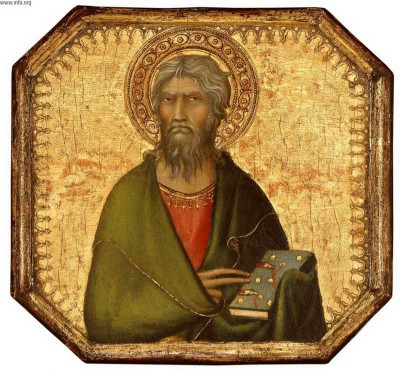

Everyone knows it, is angered by it. Jesus, in full knowledge of this, walks along the seashore, calling first Simon and Andrew, then James and John, from their work as fishermen. Come, and follow me.

They cannot free John. But they can take up the work, as they have taken up the nets in the sea. They can become fishers of men, Jesus tells them. And they know what that means – it is what John had been doing.

In all the gospels, these decisions seem to be instant, and without a backward glance. Yet I believe they are not, and cannot be. Following, in itself, is difficult. It’s hard not to backseat drive. It’s hard not to get bored, to want to stop, hard not to ask when the trip will be over, the ‘are we there yet’ questions. And in each of these, commitment becomes again a question.

Cheryl Strayed, in telling her own story of her 1500 mile hike along the Pacific Crest Trail, which she undertook to redeem her life from the self-destructive course in which she had spent several years, and from the fear and rage that had lived in her heart since the sudden death of her beloved mother when Cheryl was only 20, writes about her commitment to this journey as a journey in itself, a journey that became part of her journey.

Cheryl Strayed, in telling her own story of her 1500 mile hike along the Pacific Crest Trail, which she undertook to redeem her life from the self-destructive course in which she had spent several years, and from the fear and rage that had lived in her heart since the sudden death of her beloved mother when Cheryl was only 20, writes about her commitment to this journey as a journey in itself, a journey that became part of her journey.

There was the first, flip decision to do it, followed by the second, more serious decision to actually do it, and then the long third beginning, composed of weeks of shopping and packing and preparing to do it.

There was the quitting my job as a waitress and finalizing my divorce and selling almost everything I owned and saying goodbye to my friends and visiting my mother’s grave one last time.

There was the driving across the country from Minneapolis to Portland, Oregon, and a few days later, catching a flight to Los Angeles and a ride to the town of Mojave and another ride to the place where the Trail crossed a highway.

At which point, at long last, there was the actual doing it, followed by the grim realization of what it meant to do it, followed by the decision to quit doing it because doing it was absurd and pointless and ridiculously difficult and far more than I expected it would be . . . And then there was truly doing it.

At which point, at long last, there was the actual doing it, followed by the grim realization of what it meant to do it, followed by the decision to quit doing it because doing it was absurd and pointless and ridiculously difficult and far more than I expected it would be . . . And then there was truly doing it.

These things must have been true of the disciples. Certainly the quitting of their jobs required some decency, some words about why, and some farewell. Simon, we know, had a mother-in-law, and stayed in touch enough to know when she was ill, so there must have been some goodbyes said there. And in sorting out what to take and when to go, there must have been some question, said or unsaid, about whether this was wise or foolish.

Perhaps the story of any major choice we make can be told in this way: the choice to have a child – and how you live your way into that new identity, and how many times you think you were crazy, and how many times you think it the best thing in your life, and how many times you think it ridiculously difficult.

Any profession immerses the practioner in difficult journeys through human dimensions – in crime, in disease, in ignorance – which no lawyer, doctor, or teacher ever wanted. The choice to become a disciple, a bearer of Good News, will immerse any of us in deep darkness, in which we will be the only light around.

Any profession immerses the practioner in difficult journeys through human dimensions – in crime, in disease, in ignorance – which no lawyer, doctor, or teacher ever wanted. The choice to become a disciple, a bearer of Good News, will immerse any of us in deep darkness, in which we will be the only light around.

Elizabeth Alexander, African American poet, wrote in Praise Song for the Day,

What if the mightiest word is love,

love beyond marital, filial, national. Love that casts a widening pool of light. Love with no need to preempt grievance.

Love that does not preempt grievance, embraces doubt about many things, as well as pain.

Even the rage about John’s arrest on a trumped-up charge; even the fear we all feel in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo assassinations; even the hate in the hearts of the young men who did these foul deeds; lives within the love that casts a widening pool of light, the love with no need to preempt grievance. Signing on to this long trail, this journey through miracle and slaughter, can’t have come to them without plenty of long nights of the soul, plenty of questions.

I knew a man, a wonderful man, a pastor who had for years been immersed in the heart of the struggles for freedom in South Africa, his life for those years one long prayer for it to be over and freedom to come, yet, after it came, he looked back on those years, those struggles, as the best in his life. As the time when he was most alive. As something he would do again in a heartbeat, and something he knew he could never do again.

I knew a man, a wonderful man, a pastor who had for years been immersed in the heart of the struggles for freedom in South Africa, his life for those years one long prayer for it to be over and freedom to come, yet, after it came, he looked back on those years, those struggles, as the best in his life. As the time when he was most alive. As something he would do again in a heartbeat, and something he knew he could never do again.

Like the disciples, Theo Kotze spent his remaining years telling the stories of those times, inviting us to keep alert for the next inspirited moment, which he believed would be coming, and soon.

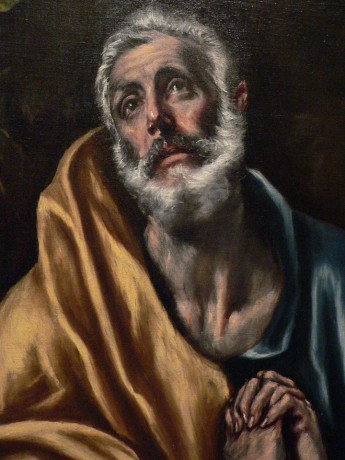

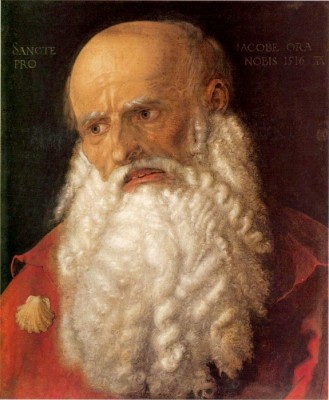

A calling is never an easy thing, and is not often a comfortable thing. Think of Jonah, think of Gideon, think of Noah, who resisted, even ran away from, the plans of God. And who questioned every step of the way, is this the right choice, should I be doing this? Think of Peter, think of Paul.

And this is how hope walks through our world —

_________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Penitent St. Peter , by El Greco Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. St. Andrew by Martini Simone. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Cheryl Strayed on the Pacific Crest Trail. image from her blog, WILD

4. St. John, by El Greco, Prada Gallery, Madrid. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. St. James the Apostle by Albrecht Durer, MFA Boston. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.