And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself. (John 12:32)

And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself. (John 12:32)

Ominous, strange, magical, mysterious, mind-boggling is the older tale from which this idea comes. It’s the tale of the bronze poisonous serpent, lifted up, that saved the people Israel in their long walk from Egypt to the Promised Land. The tale, in the Book of Numbers, is one to which Jesus made reference as he walked the dangerous streets of Jerusalem.

The tale tells how the people, struggling to stay hopeful in the arduous journey around the Red Sea, found themselves in a desperate state, as poisonous snakes appeared in their path and bit them. Many died from their venom. Before this, there had been plenty of complaining and discouragement, hunger, and discomfort. Now, they were deeply afraid, and they felt ashamed, as if their complaining had earned them these deaths. Moses praye for them, asking God to lift the curse of death. And God told Moses: make a poisonous serpent and put it upon a pole, and whenever a serpent bites someone, if that person gazes at the serpent of bronze, he will live.

And so it was. Gazing on the serpent on the pole revived the stricken, became an antivenom. But what on earth does it mean, what does it tell us about God, about Moses. And for that matter, what does the cross, on which Jesus is lifted up, tell us about God, about Jesus, about the journey his friends have made?

And so it was. Gazing on the serpent on the pole revived the stricken, became an antivenom. But what on earth does it mean, what does it tell us about God, about Moses. And for that matter, what does the cross, on which Jesus is lifted up, tell us about God, about Jesus, about the journey his friends have made?

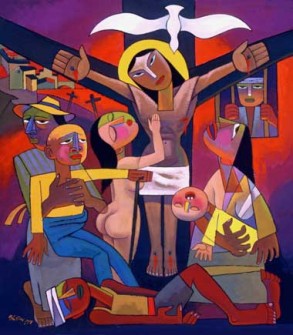

When I first began to learn the devotional use of icons, I remember Tilden Edwards offering us this distinction between seeing and gazing. Seeing, he said, was reaching out with your sight and taking hold of what you see, making it yours, part of the world your mind is making sense of. Gazing, he said, was opening your mind, your soul, in your unwavering stillness, allowing the icon to come into you and take hold of your sight, transforming your understanding of the world with its mystery.

As I grew to be able to spend an hour, or even more, gazing at an icon, I came to know that, as I became still, the icon developed motion, vibrancy, and the power to knock me into a state of wonder, from which I emerged exhausted and amazed. In the Orthodox traditions, icons are called windows or portals into mystery, because of these experiences, and in Orthodox churches they are treated as living beings because of this, much as Jews treat their Torah with the same honor.

Something like this must have happened to the people Moses led, who were stricken with snake bite and constricted with terror of death. Looking long and deeply into the face of Moses’ poisonous serpent of bronze, set upon a pole, offered them a reordering of their reality, and a transformation of their knowledge of death – and life. And this allowed them to find their way past poison, past fear and to renewed life. In this devotional mysticism they made a journey past death, into eternal life, and back again.

Something like this must have happened to the people Moses led, who were stricken with snake bite and constricted with terror of death. Looking long and deeply into the face of Moses’ poisonous serpent of bronze, set upon a pole, offered them a reordering of their reality, and a transformation of their knowledge of death – and life. And this allowed them to find their way past poison, past fear and to renewed life. In this devotional mysticism they made a journey past death, into eternal life, and back again.

John associates the cross with this, saying as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes (gazes on) in him may have eternal life. It’s about as clear as mud, what this means. Jesus is far more Moses than he is the poisonous snake, and he is not made of bronze, he suffers and dies on that pole, despite all the prayerful gazing into God he has done. But there is a similarity in the dire circumstances in Jerusalem and the cruelty in Egypt, the oppressive cruelty of the Romans, the crucified slaves there as there had been in Egypt, and the cruelty in both places has been a poisonous serpent, striking at the hope and courage of the people.

![]() Jesus himself, makes reference to this (according to John) when he is informed during this ominous week that some Greeks want to see him. Greeks. Not Jews. A larger circle of the world, and another people. The time has come, Jesus says, for those who love their life to lose it, and he reminds them how a single grain of wheat, if it dies, bears much fruit.

Jesus himself, makes reference to this (according to John) when he is informed during this ominous week that some Greeks want to see him. Greeks. Not Jews. A larger circle of the world, and another people. The time has come, Jesus says, for those who love their life to lose it, and he reminds them how a single grain of wheat, if it dies, bears much fruit.

He does not pray to be saved from death, instead he prays for the glory of God. And a response comes from heaven, which was heard in diverse ways, as a promise, as thunder, as an angel. And he continues: And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people unto myself.

His promise is not that our deaths will be individually reversed, but that we will become part of all people. All people. The thief beside him. The soldiers around him. The enemy and the ally. The unforgiveable and the unforgiving. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and all his mutilated victims. Arab Moslems, western Christians, Israeli Jews. And western Moslems, Arab Christians, Parisian Jews. This is not an argument over diplomacy, it is the forging of a new way out for the desperate, who are trapped and at the point of death in the blood feuds of the powerful, and whose certain victory will be confounded by their own instruments of torture, which, in the gazing contemplation of a dying world, will metamorphose into a Way to new life.

His promise is not that our deaths will be individually reversed, but that we will become part of all people. All people. The thief beside him. The soldiers around him. The enemy and the ally. The unforgiveable and the unforgiving. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and all his mutilated victims. Arab Moslems, western Christians, Israeli Jews. And western Moslems, Arab Christians, Parisian Jews. This is not an argument over diplomacy, it is the forging of a new way out for the desperate, who are trapped and at the point of death in the blood feuds of the powerful, and whose certain victory will be confounded by their own instruments of torture, which, in the gazing contemplation of a dying world, will metamorphose into a Way to new life.

_______________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Moses – Cathedrale Notre-Dame, Lausanne, Switzerland, 1250. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Moses and the Brass Serpent, Flemish, 17th century, unidentified artist. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Brazen Serpent, Fantoni, Giovanni. 20th c. Atop Mount Nebo, Jordan. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Iglesia Ortodoxa Griega, Greek Orthodox Church, Naucalpan, Mexico. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. Crucifixion Icon, Pietro Lorenzetti, 1340s. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Google Images.

6. Crucifixion, He Qi (Nanjing, China) Church of St. Mary, NY. Google Image.