All the world has tales of dragonslayers. The dragon is Death, a monster breathing poisonous fire, whose hunger feeds, one by one, on everyone. In their terror, townspeople sacrifice vulnerable flocks, then their young, and then their beautiful maidens (their hope for the future), to the corrupt appetites of the dragon. At last comes the Dragonslayer: pure hearted, valorous, faithful to God, compassionate, he rises as the champion of the afflicted.

All the world has tales of dragonslayers. The dragon is Death, a monster breathing poisonous fire, whose hunger feeds, one by one, on everyone. In their terror, townspeople sacrifice vulnerable flocks, then their young, and then their beautiful maidens (their hope for the future), to the corrupt appetites of the dragon. At last comes the Dragonslayer: pure hearted, valorous, faithful to God, compassionate, he rises as the champion of the afflicted.

Iconic among dragonslayers is St. George, patron saint of England (also Georgia, Egypt, Bulgaria, Aragon, Catalonia, Romania, Greece, India, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Lithuania, Palestine, Portugal, Serbia, Ukraine, Russia and Syria). He is a savior of children, damsels in distress, and Defender of the Faith.

His legends vary, but all begin with him riding into town unaware of the dragon, but quick to see the tears and fears of the people. Learning their losses, then seeing the lovely princess about to be the next sacrifice, St. George vows to save them all, calls the Dragon forth from its cave and inflicts a grievous wound with his lance. Or, the lance breaks, and he uses his sword. Or, the lance breaks, the dragon pulls him from his horse and breathes poison and fire on St. George, who falls, nearly dead, but survives through a touch of holly berries (in England), then rises to wield his sword to slay the dragon.

In John’s gospel, Jesus is the Dragonslayer, rescuing Lazarus, the brother of Mary and Martha, his dear friends. The story is very long, and half is about Jesus’ approach to this town and this confrontation with death, his meetings with the grieving sisters, his promise that Lazarus will rise.

In John’s gospel, Jesus is the Dragonslayer, rescuing Lazarus, the brother of Mary and Martha, his dear friends. The story is very long, and half is about Jesus’ approach to this town and this confrontation with death, his meetings with the grieving sisters, his promise that Lazarus will rise.

Jesus’ weapon, though, is neither a lance nor a sword. It is his tears. His tears arise in response to the tears of the sisters of Lazarus, and his courage rises in response to their faith in him. All three siblings, according to John, are dearly loved by Jesus. Yet news of Lazarus’ death alone does not bring Jesus to immediate action. It is when the sisters bring him their grief, first Martha, and then Mary, who arrives weeping and sinks to his feet, that Jesus was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. Jesus wept. Mary’s tears touch Jesus literally, falling on his sandaled feet, and spiritually.

Strengthened by Mary and Martha’s tears and awakened by his own, Jesus calls into the cave (the word John uses for the tomb), Lazarus, come out! (Martha shrinks, protesting he has been dead four days and there is a stench. In the King James version she protests, He stinketh!) Lazarus comes out, and he is both a defeated dragon of death, and a living man.

I am one of many who shrink from the thought of him, ghastly and ghostly, rotten in death yet returning to a world he has left, knowing he must leave again.

Yet I know that the maiden saved by St. George knew that death would come again for her one day.

Yet I know that the maiden saved by St. George knew that death would come again for her one day.

As did the sheep that remained in the pastures, face death another day.

As did the town. And yet their rejoicing was great, for salvation was at hand. St. George’s pure heart and strong faith spared them. There will always come another dragon, another day, but this day has been saved for life, and, in Jesus’ words, for the glory of God. St. George, iconically kneeling over the slain dragon, head bowed in prayer, would say Amen.

In John’s tale the maidens have opened Jesus’ heart, not by their innocence but by proclaiming Jesus their hero in faith. And their sacrifice has not been of their bodies, but of their love.

Later in John’s gospel, the Last Supper will be held in their house, Jesus’ last meal before he becomes the sacrifice to Dragon Death. The grievous wounds will be his own, and he will again say No to the power of the sword that Peter would wield.

The dragon will not be prevented from the kill but defeated by Jesus’ unceasingly compassionate tears, which flow for all: the soldiers who know not what they do, the thieves beside him, his mother and his beloved friends. Death’s rage will not harden his heart. And in the freshness of Magdalene’s Easter morning weeping, he will return again.

The dragon will not be prevented from the kill but defeated by Jesus’ unceasingly compassionate tears, which flow for all: the soldiers who know not what they do, the thieves beside him, his mother and his beloved friends. Death’s rage will not harden his heart. And in the freshness of Magdalene’s Easter morning weeping, he will return again.

The biblical Messiah legends (there are many in other sources) raise hopes for a reign of restorative justice (clearly a part of St. George’s work) and for a reign of peace. They are not directly about defeating Dragon Death. A few, like Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones, and Isaiah’s prophecy that there shall no more be tears and mourning, hint at this. John, alone of all the gospels, links these legends. He has Martha call Jesus the Messiah in her greeting, a sign to us that justice is an issue here. And Jesus, by his tears, shows us that survival is something we call forth in one another, pushing dragons away from the days, day by day.

Lazarus’ raising is unlike Jesus’ resurrection in that it is not eternal. What links these tales, I believe, are Jesus’ tears.

Jesus wept. It’s the shortest verse in the Bible. It’s the key verse in the raising of Lazarus. And it offers us a vision of Easter, the fruitfulness of love between friends.

____________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. St. George Slaying the Dragon, by Raphael, 1504, Louvre Museum, Paris.

Wikipedia Image.

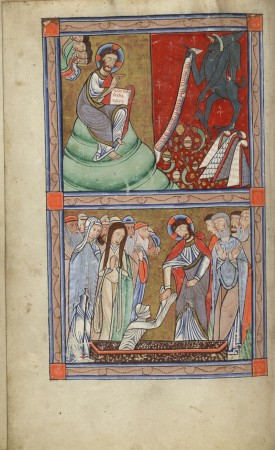

2. The Raising of Lazarus, Hunterian Psalter, 1173, Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, Scotland. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition. Note, in top scene Jesus ‘slays’ dragon death, in bottom, pulls Lazarus out.

3. For England and St. George Poster. from St. George’s Day images on Google.

4. St. George, 9th or 10th c. St. Catherine’s Monastery doors, Sinai, Egypt. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.