He fought 64 bouts in his career, and was only knocked down in one of them. But it was his bouts with the heavy weights outside the ring, who tried their best to knock him down and keep him out that have made him a hero for the ages.

He fought 64 bouts in his career, and was only knocked down in one of them. But it was his bouts with the heavy weights outside the ring, who tried their best to knock him down and keep him out that have made him a hero for the ages.

He exchanged his birth name, Cassius, a slave name, for the name of the prophet of Islam, the faith to which he converted early in his career. It was a faith in which he kept on having conversions. He converted first into the American Black Muslim faith, centered on black rights.

Years later, he left that church and became a Sunni Moslem, joining a global form of Islam rooted in faith and practice. As a Sunni Moslem, he made a Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, and along the way, inspired Moslems all around the African and Arabic world.

More recently he moved again, into Sufism, a distinct denomination of mystical and prayerful forms of Islam, to which the beloved poet Rumi belonged.

After his initial conversion, Ali tried to register as a Conscientious Objector with his draft board in Kentucky, which refused him this status for no stated reason. In 1967, Ali refused induction into the Army to serve in the Vietnam War, saying, “I ain’t got no argument with the Viet Cong. They never called me nigger.” And, “I ain’t draft dodging. I ain’t burning no flag. I ain’t running to Canada. I’m staying right here. . . . but I ain’t going no 10,000 miles to help murder and kill other poor people. If I want to die, I’ll die right here, right now, fighting you, if I want to die. You my enemy, not no Chinese, no Vietcong, no Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice.” He was sentenced to five years in prison by the US 5th Circuit Court.

Ali never served a day of that sentence. A long process ensued in the US Supreme Court, in which the justices were at first inclined to uphold his conviction. Justice Harlan, assigned to write that opinion, began reading background material on Black Muslim doctrine provided by one of his law clerks, and became convinced that Ali was sincere in his pacifism. He persuaded the court to overturn the conviction on technical grounds in 1971, a 5-4 decision.

Though afflicted with Parkinson’s Disease, Ali represented his country at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta by running the last leg of the relay and lighting the Olympic torch. He’d persevered and outlasted his powerful detractors, and emerged the winner in public opinion.

What was awesome about Ali was his surefootedness outside the boxing ring, where he extended his dignity and greatness in a culture that sought to make him a buffoon, an army grunt, a traitor to Christianity and to his nation, and even a coward.

He was no saint, either as a Christian or a Moslem. His appetites and his mistakes are documented. But in the great matches of the day – in the routine demeaning of black athletes in the public mind, in the struggles for civil rights and against the War in the 1960s, and in his confrontation with the Draft, he was David before a number of Goliaths, and he danced away from their punches with a sureness of word and deed that greatly increased the dignity of people of color, and of Moslems, in America.

In his boxing days, he became the poet laureate of the rings, penning memorable lines we have never forgotten, using his mouth as a slingshot against the giants in the press.

In Oct 1974, before regaining his title from George Foreman, he stood before the press and said, with a smile that every camera caught: Now you see me, now you don’t./George thinks he will, but I know he won’t./I done wrassled with an alligator, I done tussled with a whale./Only last week I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalised a brick./I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.

George Foreman, speaking on NPR today, said that after the bout they became good friends, and celebrated their birthdays together often.

Perhaps Ali’s greatest achievement, in the end, was growing old, in a world where few sports stars and fewer black men do. Though he was ill and his life was not easy, he got to see the ways in which America had changed for the better, he knew he had played an important part in that, and he knew he had gained recognition for his integrity.

In all his years, his instinct for following the Spirit of God was unerring. His journey to Sufism marks that as surely as his journey away from the Vietnam War. His bright spirit danced in every arena. He did, indeed, float like a butterfly, and sting like a bee.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

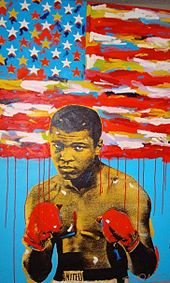

Image: Muhammad Ali pop art poster by John Stango. From the Muhammad Ali Wikipedia page.