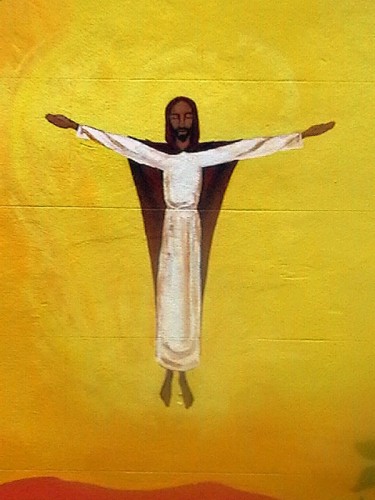

The epiphanies of Easter draw to their end, the forty days of unexpected sightings, memorable conversations, sharing bread and cooked fish in giddy joy, all the things that eased the pain of Jesus’ death, according to the Easter tales. This all ends with the Ascension, ten days before Pentecost, Jesus lofting away on clouds, or with angels, depending on which tale you read.

The epiphanies of Easter draw to their end, the forty days of unexpected sightings, memorable conversations, sharing bread and cooked fish in giddy joy, all the things that eased the pain of Jesus’ death, according to the Easter tales. This all ends with the Ascension, ten days before Pentecost, Jesus lofting away on clouds, or with angels, depending on which tale you read.

It’s a happy story, at least on the surface. John has Jesus give a loving, presaging speech about it at the Last Supper: I am no longer of this world, Jesus says, though his long agony is yet to come. Perhaps he knows that agony changes us all, and none of us are named or really known in that. But they are of this world, he continues, and prays openly, may they be completely one, and one with me, as you are one with me.

Jesus spoke of oneness that night in the shadowed hours of separation. Ascension speaks of separation on a peaceful day. And I wonder if the sorrow is any less.

Here, we are settling into an iconography of our losses from the marathon bombings. The young boy, Martin, will be forever smiling his gap-toothed smile while holding his poster, No More Hurting People – Peace. It’s the best we can do, never having known him in life. And his family have uttered Christian words, that he is at peace.

Here, we are settling into an iconography of our losses from the marathon bombings. The young boy, Martin, will be forever smiling his gap-toothed smile while holding his poster, No More Hurting People – Peace. It’s the best we can do, never having known him in life. And his family have uttered Christian words, that he is at peace.

Yet in his home, they are left with his empty bed, his empty chair at the table, his toys, his clothes, his homework where he left them. Over and over, the neon message is, he left. Morning or night, it is no easier to bear.

The iconography of Ascension we have settled on in the church exists in an endless array of stained glass art in which Jesus waves from a cloud. There are a few variations: in England’s York Cathedral a ceiling boss over the center aisle shows a ring of bare feet bottoms (the disciples) and a little ways above them, the shining bare bottoms of Jesus’ feet, with a tiny circle around them – the hem of his robe. Up, up and away!

Still, for the disciples, the sorrow must have been achingly real. The experience of being One, when transformed by separation, is a lasting pain. I know parents who have lost a child, and call themselves members of the Awful Club, in which they are now bonded to other parents like themselves, people with whom they may previously have had nothing in common, but this sharing, of the love that will not let them go, though that love is no longer in this world, now makes them one.

Still, for the disciples, the sorrow must have been achingly real. The experience of being One, when transformed by separation, is a lasting pain. I know parents who have lost a child, and call themselves members of the Awful Club, in which they are now bonded to other parents like themselves, people with whom they may previously have had nothing in common, but this sharing, of the love that will not let them go, though that love is no longer in this world, now makes them one.

Naomi Shihab Nye, the American poet born of an American mother and a Palestinian father, writes about Oneness and the terror of separation, in a story from the Albuquerque airport – place of endless leavings, endless loftings away:

Wandering around the Albuquerque Airport Terminal, after learning my flight had been delayed for four hours, I heard an announcement: “If anyone in the vicinity of Gate A-4 understands any Arabic, please come to the gate immediately.” Gate A-4 was my own gate. I went there. An older woman in full traditional Palestinian embroidered dress, just like my grandma wore, was crumpled to the floor, wailing loudly. “Help,” said the flight service person. “Talk to her. What is her problem? We told her the flight was going to be late and she did this.”

I stooped to put my arm around the woman and spoke to her haltingly. The minute she heard any words she knew, however poorly used, she stopped crying. She thought the flight had been cancelled entirely. She needed to be in El Paso for major medical treatment the next day. I said, “No, we’re fine, you’ll get there, just later, who is picking you up? Let’s call him.”

We called her son and I spoke with him in English. I told him I would stay with his mother till we got on the plane and would ride next to her–Southwest. She talked to him. Then we called her other sons just for the fun of it. Then we called my dad and he and she spoke for a while in Arabic and found out of course they had ten shared friends. Then I thought just for the heck of it why not call some Palestinian poets I know and let them chat with her? This all took up about two hours.

She was laughing a lot by then. Telling about her life, patting my knee, answering questions. She had pulled a sack of homemade mamool cookies–little powdered sugar crumbly mounds stuffed with dates and nuts–out of her bag–and was offering them to all the women at the gate. To my amazement, not a single woman declined one. It was like a sacrament. The traveler from Argentina, the mom from California, the lovely woman from Laredo–we were all covered with the same powdered sugar. And smiling. There is no better cookie.

She was laughing a lot by then. Telling about her life, patting my knee, answering questions. She had pulled a sack of homemade mamool cookies–little powdered sugar crumbly mounds stuffed with dates and nuts–out of her bag–and was offering them to all the women at the gate. To my amazement, not a single woman declined one. It was like a sacrament. The traveler from Argentina, the mom from California, the lovely woman from Laredo–we were all covered with the same powdered sugar. And smiling. There is no better cookie.

This can still happen anywhere. Not everything is lost.*

Ascension brings Pentecost, and both of them happened in Shihab Nye’s story, as they happen in our lives: by surprise; in varying dimensions of pain; when we open ourselves to one another; and we do that because we have been lost, lost, and someone found us, too.

The sacrament of Oneness comes on wings of Spirit and touches our spirits. Sometimes leaving powdered sugar on our clothes. Or someone else’s tears. And the joy of kindness, given and received.

Ascension is not a movement in which Jesus exits from the nearness of being a living and immediate teacher, to assume a new role as a distant and spiritualized Savior. Ascension is a reaching. Reaching around a chasm of separation, finding there is still something to share.

* by Naomi Shihab Nye Gate A-4 from Honeybee, c. 2008

__________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Ascension. Bologna, Niccolo di Giacomo da, 1350 -1400,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library,

Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Martin Richard, Facebook photo.

3. Mural of Christ Ascending to Heaven, on a graffiti wall in Bristol, England, 2003. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Arab Women Grinding Coffee in Palestine, Library of Congress, 1905

Vanderbilt Divinity School, Art in the Christian Tradition.