Lynchings: for black Americans, they were a perpetual fear and a regular danger in southern states. And especially for young black men. White men, including police, were fired up by the KKK, brought together to sing and pray and drink whiskey, while being exhorted to defend their honor and the honor of white women, from disrespectful behavior by young black men.

Lynchings: for black Americans, they were a perpetual fear and a regular danger in southern states. And especially for young black men. White men, including police, were fired up by the KKK, brought together to sing and pray and drink whiskey, while being exhorted to defend their honor and the honor of white women, from disrespectful behavior by young black men.

Disrespect could take any form: not looking down when spoken to; saying something other than Yessir; smiling while making eye contact, which would be interpreted as leering, or at the least, as a challenge. The truthfulness of the white people who reported disrespect went without question, in the honor-code-minded propriety of southern white manhood.

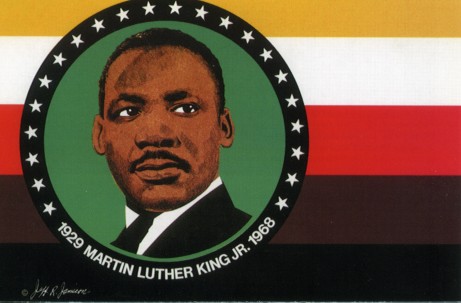

Half a century later the lives of young black men are still in danger. Half a century after Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks and many thousand black people marched and sat in to protest the white honor codes that condemned black people to live without respect, and condemned black men to die anywhere, anytime. Half a century after laws enacting white honor codes in the form of segregation were struck down.

Young black men are no longer lynched, but shot down, even when unarmed, by white police, and for similar issues of disrespect toward white men, who report feeling fear for their own lives, and who perceive young black men to be menacing them, even though security cameras and dashboard cameras show this not to be the case.

Television, new when Martin Luther King led marches and spoke on the Washington Mall, played a huge part in challenging the story and the honor codes, because the whole nation was watching. In our era, security cameras and dashboard cams are also new and making a difference. But the resistance against them, against the challenges story they show, is huge. And there is public insistence, spread far beyond the south, that black men are menacing and white are noble.

Television, new when Martin Luther King led marches and spoke on the Washington Mall, played a huge part in challenging the story and the honor codes, because the whole nation was watching. In our era, security cameras and dashboard cams are also new and making a difference. But the resistance against them, against the challenges story they show, is huge. And there is public insistence, spread far beyond the south, that black men are menacing and white are noble.

The story white men tell today is is still about an honor code, one that is written deep in the psyche of this nation: the virtuous man stands alone in a sea of crime, a black and stormy sea. He stands alone as a rugged individual. He uses his weapon for good, so that justice will prevail.

A large part of the white American population will hear no evil about white policemen, and not much good about young black men, saying they should raise themselves up through rugged individualism, not walk around with a disrespectful demeanor toward the police, or toward anyone.

The same white population that demands respect for the police as a form of cultural honor, and is quick to call both white and black young men punks for a range of perceived behaviors, from tattoos to haircuts to drinking underage, behaves disrespectfully toward women, gays, children and animals. Conservative white men are unwilling to allow gay marriage, racial intermarriage, and are skeptical about abuse within the family and animal rights. And this same portion of the white population, according to pollsters, responds to Donald Trump with admiration: because he has made money, because individualism and success are his mantra, and because his public insolence lends an aura of dignity to theirs.

The polic e have become heroes to the white working class population. In them Americans cling to the icon of the lone rugged hero, taking on a sea of wicked others. And the social scapegoats who fill the role of the wicked others are, as they have always been, black men, though Arabs, Sikhs, and even Latino men, are also acceptable scapegoats.

e have become heroes to the white working class population. In them Americans cling to the icon of the lone rugged hero, taking on a sea of wicked others. And the social scapegoats who fill the role of the wicked others are, as they have always been, black men, though Arabs, Sikhs, and even Latino men, are also acceptable scapegoats.

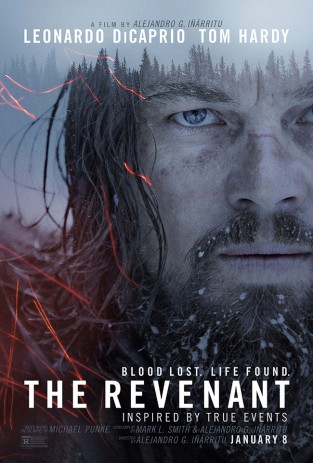

It is hard in America to get people’s interest in other stories, especially hard to get them interested in stories of evil in which the society is tacitly complicit, stories where the victims cannot be saved by one lone hero, stories where the victims are not white. The Golden Globe Awards this year nominated two fine films, Spotlight and The Big Short in the Best Film category. Both films tell stories of this kind of systemic injustice. Another film, The Revenant, was also nominated, and won the prize.

The Revenant, which means ‘someone who has risen from the dead’, is a story of revenge, a story about one lone man who survives certain death in order to kill his betrayer.

Spanish director Alejandro Inarritu is a masterful film maker and story teller, and he has added a sub-theme of racial injustice to the biographical story of Hugh Glass, by including a Pawnee wife and son, who are not part of the original book, and who set Glass apart because he genuinely loves the Pawnee, and speaks their language fluently, whereas all the other white people in the movie are race haters who murder Natives, lynching them as easily as the KKK lynched blacks, and as easily as white police shoot them. In The Revenant the Pawnee are honorable people, and the white men, both American and French, are savage beasts. In the films Spotlight and The Big Short, the victims are poor, white and black, and some are immigrants, while the perpetrators are their social superiors, and are white.

The take-away from the Golden Globes Awards is that these stories are not as wonderful to us as a story in which one noble man defeats evil doers by being better at violence than they are.

We are addicted to this hero model as our vision of salvation. We have even made Martin Luther King into such a legend, a man who stands above the rest in wisdom, Spirit, and nobleness. We pay little attention to the community that surrounded him and supported him, and to the ways in which he drew spiritual sustenance from them.

In a similar way, we twist the story of Jesus into a story of a rugged, individualistic hero, the One Who Rose From the Dead. We concentrate our attention on his unique, supernatural acts. The main gospel story tells how he brought a group of poor uneducated men together and taught them how to persuade others to choose to do good and to belong to each other as brothers and sisters, rather than to be rugged individualistic heroes. The gospel tells us that Jesus did not rise from the dead to avenge his murderers, but forgave them.

Perhaps, in honor of Martin Luther King we will choose which Martin, and which Jesus, we will follow in the year ahead: the one who calls us to shared responsibility for one another’s welfare; or the unique one who might save us individually. The one who walked with the poor and the despised; or the one who throws evildoers into hell? The one who raises victims from the dead; or the one who wreaks revenge on his betrayers. Wait: isn’t the one who wreaks revenge the Devil? Whose side are we on?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Martin Luther King Poster.

2. -Lynching of six African Americans in Lee County, GA 20 Jan 1916. Wikipedia page image, for American Lynchings.

3.Screenshot of phone video taken by eyewitness Feidin Santana, showing Officer Michael Slager shooting Walter Scott. Screenshot on wikipedia.org, and also on Five thirty eight.org

4. The Revenant poster.

5. Martin Luther King poster.