Religion and terror – inseparable in Jesus’ time, explosive in our own. Their combustible fusion led to his death and has been a lit fuse — in Ireland between Catholics and Protestants, in Jerusalem between Israelis and Palestinians, in the American south between white Christians and black Christians, in India between Hindus and Moslems, in the Balkans between Christians and Moslems, and in sporadic acts of violence in recent years in European and American cities.

Religion and terror – inseparable in Jesus’ time, explosive in our own. Their combustible fusion led to his death and has been a lit fuse — in Ireland between Catholics and Protestants, in Jerusalem between Israelis and Palestinians, in the American south between white Christians and black Christians, in India between Hindus and Moslems, in the Balkans between Christians and Moslems, and in sporadic acts of violence in recent years in European and American cities.

In the sensationalism of hate, the response that has defused these situations has been works of nonviolence.

We make much of the joy of Pentecost, the Day of the Spirit, often treating it as a public gala, forgetting that the central gift was peace-filled understanding in a time of unspeakable public atrocities. Pentecost was a phenomenon that occurred between people separated by custom, culture, cult, and lack of common language. And we easily overlook the disapproval voiced by critics who were there, who scoffed at the sudden unity of spirit in the crowd and called them drunks, not filled with hope but high on the substances that dim the mind.

In a conversation born of deep faith and agonizing experiences, a man who lived through the troubles in Ireland, two Moslem women, one of whom had lived through the war in Bosnia, the other working now with Moslem communities in America, a rabbi, and a veteran of the Civil Rights struggles in the American south talked about ways in which people united by shared faith were able, in these terrifying situations, to act nonviolently and in doing that, to transform the fires of wrath into the fire of the Spirit, which burns without consuming, creating light in darkness rather than ash and rubble.

In a conversation born of deep faith and agonizing experiences, a man who lived through the troubles in Ireland, two Moslem women, one of whom had lived through the war in Bosnia, the other working now with Moslem communities in America, a rabbi, and a veteran of the Civil Rights struggles in the American south talked about ways in which people united by shared faith were able, in these terrifying situations, to act nonviolently and in doing that, to transform the fires of wrath into the fire of the Spirit, which burns without consuming, creating light in darkness rather than ash and rubble.

Jocelyne Cesari, a Harvard Divinity School lecturer on Islamic studies, said mosques in America are intolerant of radicalism, and participating in the community life of the mosque is a good way to prevent terrorism. Cesari continued, that those who have not been socialized in Islamic teaching or lifestyle, such as the accused bombers, “tend to be much more vulnerable to the radical speech online because they have no point of reference. In the West, we need more Islam in terms of religion,” said Cesari, “and much, much less the ideological positions on Islam.”

As someone who lived through the Bosnian war, Zilka Spahic Siljak, a visiting lecturer on women’s and Islamic studies, said she still finds it impossible to understand how such violence could have erupted in her homeland almost overnight between people who had been peaceful neighbors. The war was driven by politics and economics, but eventually religion became a way of pitting people against one another, she said. Yet in the war’s aftermath, religion became key to reconciliation. Interfaith dialogue with those who were ready to change “was very important for us in the Balkans.

As someone who lived through the Bosnian war, Zilka Spahic Siljak, a visiting lecturer on women’s and Islamic studies, said she still finds it impossible to understand how such violence could have erupted in her homeland almost overnight between people who had been peaceful neighbors. The war was driven by politics and economics, but eventually religion became a way of pitting people against one another, she said. Yet in the war’s aftermath, religion became key to reconciliation. Interfaith dialogue with those who were ready to change “was very important for us in the Balkans.

HDS Dean David Hempton spent his college years surrounded by the sectarian violence in Northern Ireland’s capital, Belfast, where he said religion was only one contributing factor to the fighting. The multilayered conflict also involved competing nationalities, cultural traditions, access to economic opportunities, policing, and security forces. Watching the conflict unfold, Hempton said, he began to understand that violence radicalizes people, that there is danger in stereotyping, and that it is important to check one’s own moral choices and views constantly to try “to see events from the other side.”

Harvey Cox, a veteran of the American struggles for Civil Rights in the era of legal segregation, spoke of the importance of placing actions of faith in the context of violence: that prayer and peaceful presence in the midst of hate-filled objectors became the flame of the Spirit that triumphed in peace; that it is not religion apart, but religion practiced in the midst of hate that unmasks and disempowers false religion. Rabbi Finestone echoed his thought in her statement that God is best found in the deeds of kindness that are done in times of terribly evil deeds.

This unusual conversation happened last week, at Harvard Divinity School. When it ended, the world had not changed in a notable way, but each of us there carried away some new words and new concepts, and the power to connect them to other conversations. And this sowing of the Spirit, whose seeds will rise to become a new day, is in fact quite like the first Pentecost.

We were a few hundred folk, far smaller than the first Pentecost, but just as diverse, many from other nations, speaking a number of languages into cell phones or typing on Ipads, women wearing hijabs sitting near men who were pastors, some black, some white, some Hispanic, some in their 20s, a few in their 80s, and most in between.

We were a few hundred folk, far smaller than the first Pentecost, but just as diverse, many from other nations, speaking a number of languages into cell phones or typing on Ipads, women wearing hijabs sitting near men who were pastors, some black, some white, some Hispanic, some in their 20s, a few in their 80s, and most in between.

Though there was wine after the talk, no one called us drunk, but the gruff chorus of Americans who trust only in military power would have called us foolish and this a waste of time.

The vital force of such conversations, seeking to find sense where none seems possible, has its own amazing historical trail: from Gandhi to Martin Luther King to Nelson Mandela, from William Lloyd Garrison and the abolitionists to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the suffragettes, from Yad Vashem to Stonewall to environmentalists hugging the fence around the White House, from people running toward the bombs to help the victims to Amanda Barry being strengthened in her captivity by seeing rallies of people who remembered her though they had no idea into what abyss she had fallen: in all of these conversations, the power of the Spirit brings peace, joy, and understanding. It may take years, generations, to reach the goal of a new beginning. Still, in each conversation the hearts and minds of those who participate are buoyed for the endurance that lies ahead. The power of the Spirit, and the speech the Spirit gives, carry people toward freedom, in every age.

This is the promise of Pentecost: now we no longer depend solely on Jesus to be the one who understands. Now we, too, understand. And now we, too, can speak and our voices can spread the Spirit of understanding.

______________________________________________

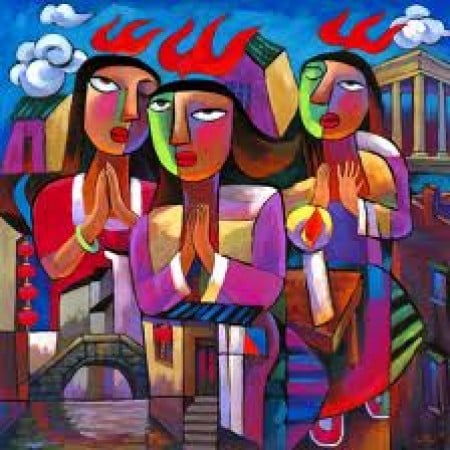

Illustrations:

1. Pentecost, Rohan Master 1430 – 1435, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris.

Vanderbilt Divinity School, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. HDS Panel, Dean David Hempton, Jocelyne Cesari, Zilka Spahic-Siljak, Harvey Cox. photo taken by Nancy Rockwell.

3. HDS Panel, Zilka Spahic-Siljak, Harvey Cox, Rabbi Sally Finestone.

Photo by Nancy Rockwell

4. Pentecost, by He Qi, China. Google Image. vanderbilt Divinity school Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

Quotations taken from the May 2013 HDS Current, an online publication.