It’s bleak midwinter – February – and black history month, when the long wintry shadow of race that hovers over America, gets some attention. The last Sunday of Epiphany shines its light on a nation where it is rare indeed for white people and people of color to worship together.

It’s bleak midwinter – February – and black history month, when the long wintry shadow of race that hovers over America, gets some attention. The last Sunday of Epiphany shines its light on a nation where it is rare indeed for white people and people of color to worship together.

Last spring, in an exhibit at the Smithsonian about slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello estate, I saw skillfully made things, silverware and china, intricately carved furniture, nails and bullets, rifles, carriages, woven linens, and silver jewelry, all made by named slaves who belonged to Jefferson, some of whom were his own children, sired as slaves and never set free.

Washington D. C. was being built, by slaves, in his lifetime, and he must have watched that construction during his presidency. In addition to the felling of trees and draining of swamps, the paving of roads and planting of gardens, slaves built The Capital Building; the Library of Congress; the White House; the Great Mall. And all of this, the proud planning of the powerful and the Promethean toiling of the oppressed, were begun with Christian prayers, and dedicated with more of the same.

Jefferson published his own Bible, deleting all miracles and the stories of Easter. He did this in a world entirely fashioned for him by slaves, who held onto the pages of scripture he had torn away, people who found strength in the evidence of things unseen, and in it endured another century and a half of enslavement and Jim Crow segregation.

I became curious to know more about this spiritual split, and how it had come about that slaves became Christian, adopting the religion of their oppressors. I found that, like Peter’s experience of the Transfiguration, the birth of the black church happened out of doors, in a tumultuous religious time.

David W. Blight*, Professor of American History at Yale University and Director of the Gilder-Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, has written that :

The Great Awakening and the Second Great Awakening swept through both the North and South periodically from the 1740s through the 1780s. As a result of the revival movements, many Americans abandoned hierarchical religion for a more egalitarian God who offered more immediate salvation. This ethos prepared people for the egalitarianism of the American Revolution

The revivalists generally did not challenge slavery, but they preached to everyone, regardless of race. The Methodists and the Baptists, in particular, welcomed converts from the black and white working population. Fearing the Christian message of spiritual equality, slave owners initially resisted evangelicals preaching to their slaves, but as the revival movement spread, a few even came to consider it their Christian duty to teach their slaves about the Bible.

A century before emancipation, then, there began to be seismic shifting in the moral and spiritual fabric of American life, and a kind of religious crazy-quilt emerged. There were the established churches, where the Bible was preached as foundational for a system of masters and slaves, and obedience was preached as righteousness. And there were revival meetings, and even revival churches, where a God who may free you and who wants your deliverance was preached, and you were urged to say Amen.

A century before emancipation, then, there began to be seismic shifting in the moral and spiritual fabric of American life, and a kind of religious crazy-quilt emerged. There were the established churches, where the Bible was preached as foundational for a system of masters and slaves, and obedience was preached as righteousness. And there were revival meetings, and even revival churches, where a God who may free you and who wants your deliverance was preached, and you were urged to say Amen.

In general white slave-owning families went to established churches, and slaves to the field meetings along with white people who could not afford slaves. But there were slave owners and members of their families who sometimes went to revivals, and there were slaves trained in religion by their owners. So a mingling of competing truths was astir.

In the established white churches, preaching centered on codes of conduct, Levitical and Pauline rules and laws, and your adherence to them as the Way of salvation. From this were forged codes of chivalrous conduct which defined what it meant to be human.

In the revival meetings in the fields, and in the churches that came from them, the great saga of Exodus, of a slave people overthrowing authority and making their way to freedom with God on their side, became bed-rock, along with the life of Jesus, a man whose paternity was murky, who was poor and labored with his hands, and who, despite all this, was the Beloved of God.

In first-century Israel, a religiously tumultuous time, the establishment used Moses and Elijah to denigrate Jesus, the street-preacher who broke some of Moses’ laws and challenged some of Elijah’s assumptions. Peter, James and John had a vision of Jesus with Moses and Elijah, Jesus illumined and transfigured as one with them. American slaves had similar visions of Jesus and Moses and Elijah, all of whom set captives free. Jesus was their Savior, not the Lord of the white slavers.

In first-century Israel, a religiously tumultuous time, the establishment used Moses and Elijah to denigrate Jesus, the street-preacher who broke some of Moses’ laws and challenged some of Elijah’s assumptions. Peter, James and John had a vision of Jesus with Moses and Elijah, Jesus illumined and transfigured as one with them. American slaves had similar visions of Jesus and Moses and Elijah, all of whom set captives free. Jesus was their Savior, not the Lord of the white slavers.

David Blight goes on: African Americans played a major role in their own conversion, and for their own reasons. Africans brought to America initially resisted giving up the religions of their forefathers, but over time, large numbers of slaves found the biblical message of spiritual equality before God appealing and found comfort in the biblical theme of deliverance. Becoming Christian was a way of becoming American, in a country which would not offer slaves any other equality or citizenship, but did allow this citizenship in the Kingdom of God.

Slaves had no books, so they put these stories into spiritual songs. (If you click on the Hymns tab, the link there will take you to Louis Armstrong singing Go Down Moses.) And they adopted a call-and-response technique in preaching which allowed everyone to take the sermon home and re-run it in their heads.

David Blight continues: A first generation of black preachers arose from this revival movement, and they planted congregations on plantations and in cities across the south. George Liele and his proteges, Andrew Bryan and David George, built the first black Baptist churches in Georgia and South Carolina during the height of the Revolution. The black Baptist movement thrived in British-occupied Savannah and Charleston. After the war, the geographical reach of their combined ministries was remarkable. By 1790 George Liele had emigrated to Jamaica with the Loyalists, and he preached regularly to 350 converts. David George established seven churches in Nova Scotia. By 1800 Andrew Bryan’s First Baptist Church of Savannah had grown to a congregation of 700.

Lemuel Haynes, born to a white mother and an ‘African’ father in 1753, was sold as an infant of 5 months to a man in Massachusetts, on condition he be set free at 21. Part of the agreement required educating him. Freed in 1774, he joined the Minutemen and fought in the Revolution. After the war he began writing extensively against the slave trade and slavery. He became a Congregational minister in 1783, and served white congregations in Connecticut, Vermont, and upstate New York. In each parish, a small disgruntled group that did not want a black minister eventually ousted him.

Although these early leaders were black men, women were the majority of the membership of early black congregations, and they frequently took the lead in conversion. Many of these women claimed, and actually exercised, the right to preach, and a large number of them were exhorters (informal preachers).

There’s a holy story here, of the Spirit bursting forth from the imprisoning doctrines of the established churches, and of the gospel being proclaimed in its true power for setting people free. There’s a heart-melting story here, of men in bondage and women used as breeding cattle hearing stories of hope that offered them strength to hold on. And there’s a cruel and regrettable story here, of churches defending and upholding the system of human slavery upon which the economy of the entire nation was based, pronouncing slave owners bona fide Christians if they lived by their codes, and denouncing a black ordained man because of his race.

There’s a holy story here, of the Spirit bursting forth from the imprisoning doctrines of the established churches, and of the gospel being proclaimed in its true power for setting people free. There’s a heart-melting story here, of men in bondage and women used as breeding cattle hearing stories of hope that offered them strength to hold on. And there’s a cruel and regrettable story here, of churches defending and upholding the system of human slavery upon which the economy of the entire nation was based, pronouncing slave owners bona fide Christians if they lived by their codes, and denouncing a black ordained man because of his race.

In the midst of these stories, the Transfiguration stands as an archetype, reminding us that revelation is a form of freedom, and has the power to pull people out of the confusion of public voices, the mire of mudslinging, and even their own pain, into a moment when they can see their freedom coming. The Great Awakenings gave birth to the black church, which has its roots in revelation, in the experience of transfiguration, and in the evidence of things unseen.

_______________________________________________

*The information quoted in this post is from a PBS online article on The American Revolution and African American slave Christianity, written by David Blight.

David Blight is the author of American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era, (Harvard University Press, 2011); and A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Narratives of Emancipation, (Harcourt, 2007). Other published works include a book of essays, Beyond the Battlefield: Race, Memory, and the American Civil War ; and Frederick Douglass’s Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee. Blight is the editor of and author of six books, including When This Cruel War Is Over: The Civil War Letters of Charles Harvey Brewster; Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave; co-editor with Robert Gooding-Williams, of W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk; co-editor with Brooks Simpson, Union and Emancipation: Essays on Politics and Race in the Civil War Era; and Caleb Bingham, The Columbian Orator.

Illustrations:

1. Transfiguration, by Rafael, Vatican City, Rome. St. Peter’s. 1515-1520. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition,.

2. Slaves Waiting for Sale, 1861, by Eyre Crowe, Heinz Collection, Washington D.C. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Captive Slave, 1827, by John Philip Simpson, Art Institute of Chicago. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition,.

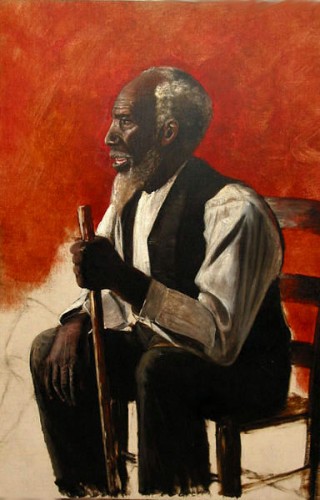

4. Uncle Alfred, c. 1885, oil on canvas, painter unknown, in a private collection. Uncle Alfred was born a slave at The Hermitage, and lived on that property all his life. After the Jacksons left, he became a tour guide and caretaker there. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition,.

5. Transfiguracion del Divino Salvador del Mundo, San Salvador, El Salvador, The Metropolitan Cathedral del Divino Salvador del Mundo. Artist unknown. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition,.