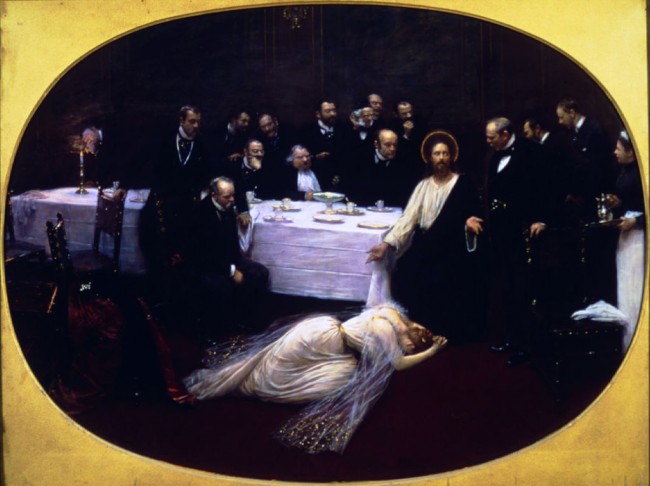

The woman on the floor, in John Beraud’s painting, brings the world’s oldest profession into the picture. She is kissing Jesus’ feet, and rubbing them with oil, using her hair to caress and anoint him. Her tears are part of the anointing, and her love.

This long-remembered moment of intimacy takes place in the house of Simon the Pharisee, a man of rigorous self-control, whose righteousness is disciplined and habitual. And in his own mind, because of this, he is closer to God than she. It is he who identifies her as a public sinner, which is how we know her profession. He has invited Jesus to dine at his home, along with a number of guests. This woman is not a guest. She has entered unbidden, and come to Jesus’ chair, where she began to bathe his feet with her tears and to dry them with her hair. Then she continued kissing his feet and anointing them with ointment, according to Luke.

Simon, indignant, objects that Jesus knows this woman is a sinner, and makes himself unclean by allowing her to touch him. Jesus asks whose heart will be more grateful and loving, the one who is forgiven for nothing much or the one who is forgiven for large and multiple sins. They agree it is the one forgiven much. The story ends with indignant whispering among the invited guests, who is this who dares to forgive sins?

Simon, indignant, objects that Jesus knows this woman is a sinner, and makes himself unclean by allowing her to touch him. Jesus asks whose heart will be more grateful and loving, the one who is forgiven for nothing much or the one who is forgiven for large and multiple sins. They agree it is the one forgiven much. The story ends with indignant whispering among the invited guests, who is this who dares to forgive sins?

Jesus makes the point, but nothing changes at Simon’s table: the feelings remain the same. And the bleakness of the Church is this unlearned lesson, lived out in every era, in every denomination: despite the story, written and read, nothing changes: ill will for the woman on the floor remains the same.

The first cup of Eternal Life given by Jesus was given to a woman who had had five husbands, and, the one you have now is not your own, he said. Jesus entered the circle of righteous men who were stoning a woman for adultery, and standing with her, accused them of impure hearts. Jesus ate with prostitutes. He defended Mary’s choice to sit and learn with the men rather than work with her sister in the kitchen. He became so intimate with Mary that he wept in response to her tears for her brother, and then raised him to life – for her. And he may have been married to Mary Magdalene, who had once been possessed by seven demons. The evidence for marriage is that, in all four gospels, she, not his mother, led the women who went to anoint his body, and in all four gospels, she was the first to know of Easter.

The first cup of Eternal Life given by Jesus was given to a woman who had had five husbands, and, the one you have now is not your own, he said. Jesus entered the circle of righteous men who were stoning a woman for adultery, and standing with her, accused them of impure hearts. Jesus ate with prostitutes. He defended Mary’s choice to sit and learn with the men rather than work with her sister in the kitchen. He became so intimate with Mary that he wept in response to her tears for her brother, and then raised him to life – for her. And he may have been married to Mary Magdalene, who had once been possessed by seven demons. The evidence for marriage is that, in all four gospels, she, not his mother, led the women who went to anoint his body, and in all four gospels, she was the first to know of Easter.

Where did his sympathy for women, and especially for women who were considered sinners, begin? Perhaps it came from his wisdom that the way we live is not what makes God love us, and that God loves the passionate longing in our nature. And perhaps his love of women who were called sinners grew in him because his mother was called that: she who was pregnant before she was married; she who taught him she had borne him for God, and not for a particular husband.

Surely his understanding of passion began as a child at her knee, even as a babe at her breast. But his own passions may be part of this love, his own desires which are hinted at but not confirmed in the gospels:

Surely his understanding of passion began as a child at her knee, even as a babe at her breast. But his own passions may be part of this love, his own desires which are hinted at but not confirmed in the gospels:

his desire for Mary, whom he defends again and again (see 3/10, A Beautiful Thing, in Archives);

his desire for Magdalene, who is at the heart of his Easter;

his desire for the beloved disciple who lay in his bosom at the Last Supper;

and then there is the enigmatic detail of the young man who runs up to him at Gethsemane and drops his loincloth – what desire is in this, and is it only in the young man, or in both of them?

Alas, the Church has drained Jesus’ life of all desire, and insisted that his mother never felt desire, that neither she nor he experienced sexual intimacy or longing. The Church has built itself into the Church of Simon, extolling the virtues of abstinence, at least until marriage if not lifelong, and of sex within marriage to procreate children, not to satisfy desire. The Church has proclaimed that these are the habits that lead to heaven, and desire is a tool of the Devil. Yet this sinful woman appears in three gospels, and in each she involves Jesus in a different argument, and in each he defends the morality of her passion.

When birth control pills first became available in the 1960s, the church was scandalized and disapproving. Then came the abortion wars. These were soon followed by the single-mother wars – a US election campaign was waged over a fictional single mother on TV. After that, the gay wars began. And now, the marriage wars are being waged, whether gays should be allowed to marry and have children, and whether women who do not marry but have children are social sinners, whether it is possible to raise a human being without a father in the house; whether two fathers or two mothers are the ruin of a child. In other words, the cultural argument is over a sole model of moral life in America: parents pushing prams. In the Church of Simon, these questions are paramount, and they define the faith practiced there.

But in the Church of Jesus there are no such questions. The woman on the floor is near the center of the painting. The table welcomes her and puts Simon to the test: are you willing to eat with her, and to call her Sister? For it is the outpouring of her heart that makes her holy. And it is her practices of desire that have made her heart so large. There is no model of holy family life in Jesus’ church, only the example of generously loving hearts that accept all. And the option of having an adult sexual life without children, exploring myriad other ways to give serve God, through art, public service, or justice action, is welcomed as the road that Jesus and most of the disciples took, an adventuresome road, in which we do not fear but trust that grace will abound.

But in the Church of Jesus there are no such questions. The woman on the floor is near the center of the painting. The table welcomes her and puts Simon to the test: are you willing to eat with her, and to call her Sister? For it is the outpouring of her heart that makes her holy. And it is her practices of desire that have made her heart so large. There is no model of holy family life in Jesus’ church, only the example of generously loving hearts that accept all. And the option of having an adult sexual life without children, exploring myriad other ways to give serve God, through art, public service, or justice action, is welcomed as the road that Jesus and most of the disciples took, an adventuresome road, in which we do not fear but trust that grace will abound.

As his mother Mary sang before he was born: he lives to scatter the proud in the imagination of their hearts, to tear down the mighty from their thrones; to exalt the lowly; and to fill the hungry (and he includes desire as hunger) with good things.

______________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Home of Simon the Pharisee, by Jean Beraud, 1849 – 1935, Wikipedia, US Public Domain.

2. Feast at the House of Simon the Pharisee, by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1630, Wikipedia image.

3. Asian Magdalene Anointing Jesus. Image used on many religious blogs and pinned on Pinterest’s Religious Art page. Not offered for sale on any gallery page. Unidentified artist.

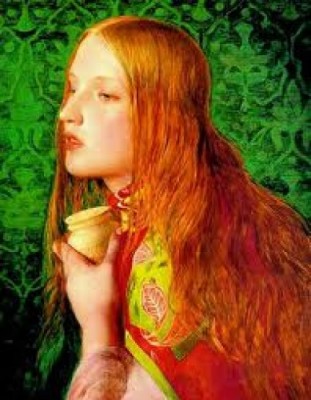

4. Anointing, Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys. Mary Magdalene. ca. 1860

Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. Feast at Simon’s House, by Bernardo Strozzi, 1630

Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.