The Australian film, Tracks, tells the true story of Robyn Davidson, a young woman who, in 1977, trekked nearly 2000 miles through the Australian wilderness (mostly desert), accompanied by four camels and a dog. Davidson is struggling to deal with her own spiritual turmoil, which unfolds while she is walking in flashbacks, tears, determination, and grit. Her mother committed suicide when she was 11. Her father, a worker at a remote cattle station, sent Robyn to live with his sister, and from there she went to boarding school, then to a self-destructive life in the city, which included drugs. Her trek is a desperate attempt at a new beginning – a pilgrimage in the wilderness to prove to herself that she can survive. It is also a death-defying walk.

The Australian film, Tracks, tells the true story of Robyn Davidson, a young woman who, in 1977, trekked nearly 2000 miles through the Australian wilderness (mostly desert), accompanied by four camels and a dog. Davidson is struggling to deal with her own spiritual turmoil, which unfolds while she is walking in flashbacks, tears, determination, and grit. Her mother committed suicide when she was 11. Her father, a worker at a remote cattle station, sent Robyn to live with his sister, and from there she went to boarding school, then to a self-destructive life in the city, which included drugs. Her trek is a desperate attempt at a new beginning – a pilgrimage in the wilderness to prove to herself that she can survive. It is also a death-defying walk.

In my ignorance, before seeing the film, the camels made no sense. They seemed an odd and exotic choice, until I learned that the first Europeans in Australia had imported a few to help them cross the vast desert. Then the trains came, and the camels were turned loose in the desert to fend for themselves. And now there are over 50,000 camels, more than in any other part of the world. The bitter irony of camel survival is that they are now hunted, captured, harshly tamed and sold as working beasts at remote cattle stations. Robyn Davidson worked as a tamer, to learn to handle camels and to earn a few as her pay.

Camels are part of Christmas, attached to the Wise Men from the East in every crèche set, though in fact the story of the Wise Men does not mention them. But their long journey must have required beasts of burden. And camels, mentioned in a prophecy, are now part of the Epiphany (the first ‘showing’ of the human face of God to strangers, the Magi).

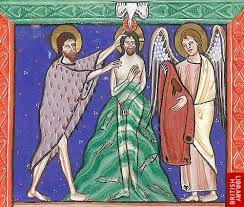

![]() The second ‘showing’, when Jesus goes into the wilderness to be baptized, also has a camel. It is John himself, clothed in a camel skin, as the gospels make a point of mentioning. And therefore John, in shedding human clothing and wrapping himself in camel skin, has to some degree identified as a camel.

The second ‘showing’, when Jesus goes into the wilderness to be baptized, also has a camel. It is John himself, clothed in a camel skin, as the gospels make a point of mentioning. And therefore John, in shedding human clothing and wrapping himself in camel skin, has to some degree identified as a camel.

The American film, Wild, tells a similar story to Tracks, a story of a young American woman, Cheryl Strayed, who walked the Pacific Crest Trail, a distance of more than 1500 miles, seeking to find her way through a profound grief over the death of her mother at 45, when Strayed was still in college. Strayed, orphaned, became self-destructive. She, too, learns through her pilgrimage, which is physically punishing and at times dangerous, that she can survive.

In the film Tracks, part of what unfolds is the spirit of camels, about whom I knew only that they are hard to handle and they spit. The film shows their bondage, their tragedies, their humor, and by the end, their love, and unfolds the same qualities in Robyn Davidson.

In the film Tracks, part of what unfolds is the spirit of camels, about whom I knew only that they are hard to handle and they spit. The film shows their bondage, their tragedies, their humor, and by the end, their love, and unfolds the same qualities in Robyn Davidson.

And all of this moves me to consider that John, too, was in pilgrimage in the wilderness. That John, too, had trekked to get there, and in the trekking was dealing with ferocious things in his own spirit. His rejection of human society is rooted far deeper than we can know. But his baptism of thousands, for whom he conducted a river ritual of ‘drowning’ to your old self and ‘rising’ into a new self that is now brother/sister to all ethnic groups, races and nations, even breaking the forbidden boundaries of gender and class, is a taming of the spirit as strong as the taming of a wild camel. John must have considered himself as wild as a camel, and also as strong, strong enough to survive under brutal conditions, and strong enough to carry the burdens of many travelers.

There is a roughhewn quality in Mark’s gospel. It fits the story of a man in the wilderness who wears a camel skin, better than the gospels that portray Jesus’ baptism as a kind of pageantry in which John fawns over Jesus’ majesty. In Mark, John simply gets the job done. And I am left to consider that, as the Forerunner, John has shown us the way that Jesus, too, must come, through the hard pilgrimage of spirit in which he has trekked across the earlier years, until Jesus, too, can identify with John, who has tamed the wild beast in his spirit, for the service of God.

There is a roughhewn quality in Mark’s gospel. It fits the story of a man in the wilderness who wears a camel skin, better than the gospels that portray Jesus’ baptism as a kind of pageantry in which John fawns over Jesus’ majesty. In Mark, John simply gets the job done. And I am left to consider that, as the Forerunner, John has shown us the way that Jesus, too, must come, through the hard pilgrimage of spirit in which he has trekked across the earlier years, until Jesus, too, can identify with John, who has tamed the wild beast in his spirit, for the service of God.

We make a lot of the image of Jesus as a Lamb (which, in John’s gospel, John the Baptist calls him). The poet T.S. Eliot preferred to speak of Christ the Tiger. Perhaps we ought to consider the Camel, for this man who identified with lepers and prostitutes, difficult people who spit on society, in the many encounters he unfolded in his ministry.

The Magi, like Robyn Davidson and Cheryl Strayed, set out upon a journey with an incomprehensible destination, a journey that proved to be arduous and gave them much to reflect about. It was, in fact, a baptism for them. Jesus is flung by his own baptism into wild encounters with temptation and his own spirit. What came to him, in the river, and from John the Camel man, helped him survive.

The Magi, like Robyn Davidson and Cheryl Strayed, set out upon a journey with an incomprehensible destination, a journey that proved to be arduous and gave them much to reflect about. It was, in fact, a baptism for them. Jesus is flung by his own baptism into wild encounters with temptation and his own spirit. What came to him, in the river, and from John the Camel man, helped him survive.

And in his singular and death-defying walk through his life, he shows us that even he, like Robyn Davidson and Cheryl Strayed, does not survive by himself – for no one makes it through this life alone. Like them, Jesus asks us to see that it is the whole of his journey, including his doubts, despair, demons, and not just this moment in the water, in which his Easter survival becomes possible. And it may be that all of our glimpses of God are made possible by our own trekking through days of being lost and difficult miles in which we heal.

_____________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Camels in the film Tracks, freeze frame, Google Images.

2. Camels with Robyn Davidson in Tracks – freeze frame, Google Images.

3. Orthodox Baptism Icon – Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Camels and Davidson in Tracks. freeze frame, Google Images.

5. Baptism of Jesus, 13th c. English Manuscript. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

6. Epiphany, by Giotto di Bondone. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.