Can bad things really lead to good things? Is it possible for suffering to lead to flourishing?

Can bad things really lead to good things? Is it possible for suffering to lead to flourishing?

I’m sure many of us have wrestled with these questions either in our own personal lives, in trying to be compassionate with others, or in our academic work. The transformative power of suffering was a major theme of my book Faith Makes Us Live: Surviving and Thriving in the Haitian Diaspora, yet the topic of suffering, and whether or not suffering can transform people or societies, is largely untouched by much social science.

For example, Martin Seligman, one of the founders of the positive psychology movement, explained to me that since he had spent 30 years studying depression and learned helplessness, he initially wanted to get away from bad experiences and feelings and only study good experiences and positive emotions.

The result, however, was that positive psychology too often became conflated with “happiology”–or the science of feeling good all the time. Hence, at a recent meeting with Seligman, numerous sociologists around the table argued that a robust understanding of flourishing must encompass the possibility that undergoing suffering can produce personal and common goods.

The result, however, was that positive psychology too often became conflated with “happiology”–or the science of feeling good all the time. Hence, at a recent meeting with Seligman, numerous sociologists around the table argued that a robust understanding of flourishing must encompass the possibility that undergoing suffering can produce personal and common goods.

Seligman stated, “It is so refreshing to hear people talk about suffering. I worked on suffering for 30 years; I felt like suffering needed no advocates.” He further explained that quite often it is the awful things in life that influence what people choose. For example, meaning, one of the five components of Seligman’s PERMA scheme of human flourishing, often arises out of awful things.

In his forthcoming work on human flourishing, sociologist Christian Smith makes a similar point: we can’t really understand flourishing or the good unless we examine evil or the bad.

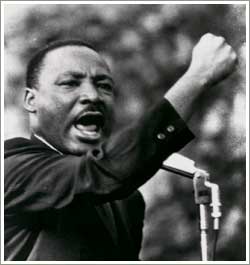

Although my work focuses more on how suffering transforms individual persons’ lives, Yale sociologist Phil Gorski also pointed out that prophets, people like Martin Luther King, have intense moral suffering because they have very wide circles of empathy with other human beings. Their suffering is not only personally transformative but also socially transformative–suffering is key to empathy, compassion, and social solidarity expressed in word and action.

Although my work focuses more on how suffering transforms individual persons’ lives, Yale sociologist Phil Gorski also pointed out that prophets, people like Martin Luther King, have intense moral suffering because they have very wide circles of empathy with other human beings. Their suffering is not only personally transformative but also socially transformative–suffering is key to empathy, compassion, and social solidarity expressed in word and action.

Does today’s generation of college students understand suffering as potentially transformative? It’s hard for me to imagine so, as suffering has moved so far out of our popular narratives which focus on happiness or flourishing as feeling good all the time, comforting ourselves, and cutting ourselves off from anyone or anything we don’t like. Although I’m a big advocate of boundaries, and I have no desire to excuse the wrong actions that can cause suffering, I’ve come to see there is no life that will be free of suffering. Rather than seeing suffering as a pure loss, we are better off if we can transform our suffering into good.

The study of flourishing need not promote suffering, but it also need not be not anti-suffering. Avoiding or minimizing suffering will be counter-productive. For most people, some form of involuntary suffering is unavoidable. In other instances, suffering or voluntary sacrifice is inherent to the exercise of mastery and acquiring skills.

Chris Peterson, another leader of positive psychology, argues that take home point of positive psychology is that simply that other people matter. If it’s true that other people matter, then no amount of self-mastery or striving for personal PERMA will suffice to flourish–for loving others always requires some sacrifice of our own self-interest. The highest PERMA or the most flourishing life, one could thus argue, is one with a proper balance between pleasure and suffering.

Seligman repeats again and again that the study of flourishing has to get away from monism–the tendency to name one highest human good. I’m not saying that suffering is the highest human good nor the only one, nor am I even saying that suffering is good, but I am saying that any study of flourishing must leave room for the goods produced by suffering and sacrifice.

Think about it: Is it possible to develop courage without suffering? What about patience? Perseverance? Developing almost any virtue that comes to mind seems to require some amount of suffering or sacrifice, doesn’t it?

So why don’t most social theories address suffering? There is something to be said for rejecting the idea that suffering is actually good. Evil is not good. But most sociological theories are based on premises from Enlightenment thinking that the purpose of identifying suffering and evil is to manage, control and eliminate everything we don’t like. This narrative of a society without suffering, of good without evil, is part of what philosopher Alisdair MacIntyre calls the most powerful narrative of contemporary society–that we live in a bureaucratically managed society where everything in our lives and in the social and material world can be controlled, predicted or mastered.

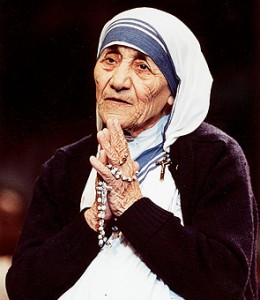

Suffering shows that we don’t always believe in the bureaucratically managed society. Suffering is a cry out against evil, a sign that we are created for something greater than we empirically observe. As such, suffering can be transformative of one’s own life and quite possibly suffering can transform society. Think of any great figure who has transformed society for the better–Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day, Mother Teresa–and you will see a figure of suffering whose life was a witness to hope for a better world.

Suffering shows that we don’t always believe in the bureaucratically managed society. Suffering is a cry out against evil, a sign that we are created for something greater than we empirically observe. As such, suffering can be transformative of one’s own life and quite possibly suffering can transform society. Think of any great figure who has transformed society for the better–Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day, Mother Teresa–and you will see a figure of suffering whose life was a witness to hope for a better world.