In my last post, I suggested that as a society, we should be more encouraging of men who are trying to combine work and family. The problem that women confront in the workplace is about both about gender and a principle of devotion to work. Many of the challenges that women face in balancing family and work are those also faced by men.

I am especially concerned with the working fathers who are serving as equal co-parents in their children’s lives, and fathers who are involved in relatively equivalent amounts (or more) of domestic work as their partners. I’m not talking about fathers who make sure to make it home for dinner—I’m talking about fathers who are often making dinner. I recognize that there are a number of men without children who still struggle to balance work/family demands, but will focus this post more on working fathers. I also refer to these men as egalitarian men; this is not meant to be a theological statement regarding their beliefs about women in the church, but rather, a statement about their family practices and beliefs that reveal relatively equal roles in their families with their partners. A blog by Dr. Scott Behson on Fathers, Work, and Family, provides an example of this population I’m considering (and also raises many of the same concerns addressed here – I suggest checking it out).

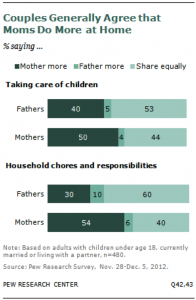

This population of working fathers is significant. Just last month, Pew Research Center released a report on the roles of moms and dads, with attention to how they spend their time and think about issues of work and family. While 56% of working mothers note it is very or somewhat difficult to balance work/family, 50% of men report the same thing. Fathers are also more likely than mothers to feel that they spend too little time with their children (46% to 23%). But perhaps most important for the topic of this post, I was interested in this chart reflecting who does more at home.

About 5% of women and men argue that men do more childcare; while close to half report that men and women are equally involved in childcare. Further, when it comes to household chores, a majority of men (and almost half of women) say that fathers do as much or more than mothers. While fathers and mothers both tend to see themselves as working more than their partners might, a large percentage of men are doing a lot at home. Yes, there is a gender gap. But when we concentrate on the median and mean, we can fail to recognize than in many families, this gender gap may not exist, while in others, it’s actually larger than the macro-level data reveals.

Challenges for Men

(1) In the last blog, I highlighted that these men are often paid less than men with traditional attitudes. Compared to more traditional men, egalitarian men with significant commitments to family can both face significant obstacles in being hired and promoted. Gillian Ranson, a sociologist at the University of Calgary, profiles a number of these working fathers in his article, “Men, Paid Employment, and Family Responsibilities: Conceptualizing the ‘Working Father.’” These men often need to leave the office early, or desire not to work every day. They are not always on call, and rarely have a partner at home who manages domestic responsibilities. The study from Cornell University (by Judge and Livingston) also suggested than egalitarian men may also be less aggressive in wage negotiations than more traditional men, and so suffer further economic penalties.

Such men may also be restricted (compared with traditional men) in the jobs that they are able to take. Families cannot easily move to support men in their careers. Egalitarian men are more likely than other men to prioritize their spouse’s career; this may sometimes entail moving for their partner, which could accompany a downward career move. They are often being compared with men who have a spouse who is dedicated primarily to the family; this is rarely something noted on their CV. While I have not seen longitudinal data, I would hypothesize that these men have less successful career trajectories than men with similar demographics and more traditional gender role attitudes.

(2) For fathers who are trying to be invested in their families, we often find that there are fewer supports for them than women. This is both an institutional and a cultural problem. In some places, women are offered more flexibility than men when it comes to balancing work and family. Second, even when paternity leave may technically be available for men, it may be discouraged. Ranson finds, for example, that mothers are still much more likely to take advantage of family-friendly initiatives.

(3) These men are also often lumped together as being ‘men’ who do not deal with the same challenges as women. Increasingly in sociology we talk about intersectionality: the idea that gender cannot be understood outside its dynamics with class and race. A recent article in the Journal of Marriage and Family by sociologists Rebecca Glauber and Kristi Gozjolko looks precisely at how issues of intersectionality can shed light on how men deal with work-family tensions.

We found that fatherhood was associated with an increase in married White men’s time spent in paid work. The increase was more than twice as strong for traditional White men than for egalitarian White men. In contrast, both egalitarian and traditional African American men did not work more when they became fathers. These findings suggest that African American men may express gender traditionalism but adopt more egalitarian work-family arrangements (“Do Traditional Fathers Always Work More? Gender, Ideology, Race, and Parenthood,” p.1133)

What I find interesting about their study is two-fold. One, the story of working fathers cannot be separated from race, as the ‘traditional’ model often heralded is one predominantly adopted by whites. Although not tested, this would lead me to suspect that some part of the wage gap between white and black men is in part due to their different family dynamics and work-family balance. Second, it suggests that just as race is important in understanding the wages men receive, so are the attitudes that men have towards gender roles and family.

At the end of the day, I found more scholars investigating these issues than I had previously known about; however, I also found a real lack of empirical data regarding the challenges and costs that these fathers face. And in our pursuits to decrease gender inequality and break down gendered stereotypes, it’s vital that such working fathers are supported.