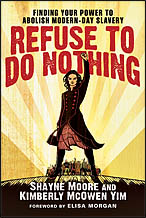

There are a lot of reasons that I should like Refuse to Do Nothing. Written by women whose consciousness has been raised to the realities of exploitation and oppression, stories of grassroots organizing toward justice, pages of practical advice on what the ordinary reader might do to combat injustice … these are things I champion and affirm. And there are many good suggestions, resources, and suggestions for taking action in the new book on global human trafficking by Shayne Moore and Kimberly McOwen Yim. It’s concise, clear, accessible, and designed for groups of women and men to learn as well as act.

There are a lot of reasons that I should like Refuse to Do Nothing. Written by women whose consciousness has been raised to the realities of exploitation and oppression, stories of grassroots organizing toward justice, pages of practical advice on what the ordinary reader might do to combat injustice … these are things I champion and affirm. And there are many good suggestions, resources, and suggestions for taking action in the new book on global human trafficking by Shayne Moore and Kimberly McOwen Yim. It’s concise, clear, accessible, and designed for groups of women and men to learn as well as act.

And yet … .

The book sits at an uncomfortable intersection of problematic theology and what Teju Cole calls the White Savior Industrial Complex.

I realize that I am not the audience for this book in several ways. It is written by and for married evangelical Christian mothers, comfortable suburban moms of means who consider themselves “blessed.” It is written for people who believe that the first action you take in response to systemic evil is prayer. I am not that person. Perhaps for those moms, this book will be the conversation that pushes them toward awareness and action in response to a real crisis that is global and local.

First, a few reflections on the theology that I find problematic in the book. Repeatedly, Moore and Yim describe themselves as “good people” living “blessed lives.” When telling the story of a young man who had lived in a refugee camp in Malawi after his family escaped the Democratic Republic of Congo, they note that “through one blessed circumstance after another, this charismatic man eventually received a scholarship …”.

So, if good things are happening to you, you are blessed. What does this imply, then, about “the slaves” as Moore and Yim refer to victims of trafficking? Why has God not blessed them? Aren’t they good people too? I have always had issues with any theology that only talks about how God intervenes in human affairs to do good things.

Earlier in the book, the authors describe in turn what it was like to learn for the first time about the horrors of human exploitation and feeling powerless at the magnitude of the problem. They plainly that “Because God is a God of grace, he met us in our stuckness.”

So, if you are “stuck” in your comfortable life, God hears you and comes to help? What about the child soldiers, the teen runaways, the women bought and sold every day? Why isn’t this God meeting and helping them? To me, any time a person claims that God answered her prayer, I have to ask “… and why not the prayers of that other woman?”

Soon after this statement, the authors note that God “has not forgotten those held against their will for evil purposes and gains of others.” So, as this story goes, God sends the self proclaimed white “abolitionist mamas” in to save the oppressed.

A quick aside: Moore and Yim use the term abolitionist to describe themselves. I find the use of that term by white women seeking to liberate poor people and women of color fraught with racial privilege. The headline on the back of the book proclaims:

“You have power. And people all over the world need you to use it.”

Additionally, the authors repeatedly liken themselves to the Grimke sisters of the nineteenth century. Coopting the language of slavery and abolition, which is what the faith-based anti-trafficking movement of the 21st century does, seems presumptuous at best. In part, this is because I see it as part of a white messiah complex that we see in many places in U.S. history as well as popular culture.

More specifically, the White Savior Industrial Complex was named by Teju Cole in a March 2012 article in The Atlantic, in response to things like Nicholas Kristof’s Half the Sky book, movie, and soon to be video game, and the Kony 2012 campaign led by Jason Russell and Invisible Children, a campaign mentioned and favorably discussed in Refuse to Do Nothing. What Cole identifies as a danger of these types of activism includes a failure to name and dismantle white privilege:

One song we hear too often is the one in which Africa serves as a backdrop for white fantasies of conquest and heroism. From the colonial project to Out of Africa to The Constant Gardener and Kony 2012, Africa has provided a space onto which white egos can conveniently be projected. It is a liberated space in which the usual rules do not apply: a nobody from America or Europe can go to Africa and become a godlike savior or, at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied.

And this is what I see happening in Refuse to Do Nothing. Regular moms in the suburbs can save the world! Here’s how!

I know … it’s better than nothing, right? It’s better than not knowing, and it is true that some readers of Refuse to Do Nothing will perhaps learn about injustices in their own cities and towns that they were previously blind to.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay over at Feministing replies to that criticism:

A knee-jerk reaction to this critique may be, “at least they are doing something,” and “wow, I guess we can’t really do anything” but this is ultimately lazy thinking. It’s not that their hearts are not in the right places, it’s that their analysis isn’t – as long as the West has the kind of economic, cultural and militaristic stronghold over places like the countries of Africa – our change efforts do not target the root or causes of oppression. Our main goal should be lobbying the government on our own soil–not short-term solutions that make us feel like we “done good.”

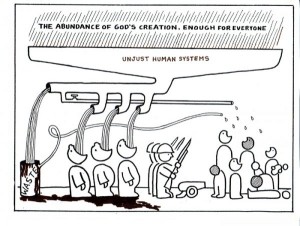

It’s the analysis of the systems of race and gender privilege and oppression that cause, support, and perpetuate human trafficking that I ultimately find lacking in Moore and Yim’s passionate call to prayer and action. How do they, I, and all of us with access to resources, power, credit, and a publisher, participate in the very systems that make human trafficking a reality today?

It’s the analysis of the systems of race and gender privilege and oppression that cause, support, and perpetuate human trafficking that I ultimately find lacking in Moore and Yim’s passionate call to prayer and action. How do they, I, and all of us with access to resources, power, credit, and a publisher, participate in the very systems that make human trafficking a reality today?

Toward the end of the book, the authors talk about altering our daily patterns of consumption, understanding where the minerals mined to make our cell phones come from, choosing fair trade products over conventionally produced items, and overall being more thoughtful consumers. These are good things, to be sure. But it leaves me as unsatisfied as did George W. Bush’s call for American’s to shop as a form of resisting terrorism after 9/11.

Cole notes the economic dimension of this issue, and talks about why we like these calls to shop our way to justice and world peace:

The White Savior Industrial Complex is a valve for releasing the unbearable pressures that build in a system built on pillage. We can participate in the economic destruction of Haiti over long years, but when the earthquake strikes it feels good to send $10 each to the rescue fund. I have no opposition, in principle, to such donations (I frequently make them myself), but we must do such things only with awareness of what else is involved. If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.

What about understanding how U.S. foreign policy weakens economies and communities around the globe? How have we participated in that, and what can we do to vote against those politicians who make it possible? What about the ways that white women of means participate in and benefit daily from what bell hooks calls the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy? These larger systems that govern the world are never mentioned or meaningfully named in Refuse to Do Nothing. And we simply cannot ever hope to attain real or lasting justice without altering such systems. Shopping is not enough.

Ultimately, the kind of analysis that I need to see in a book on human trafficking is difficult, complex, and resists easy answers. It might not be read by Shayne Moore’s and Kimberly McOwen Yim’s target audience. Perhaps that would prevent more activism, and maybe that’s not a good thing. Maybe scholars and intellectuals like me and Teju Cole need to do that work, while Moore and Yim do the work of rounding up the suburban moms. Or, maybe as long as we’re educating the masses about injustice, we need to tell the truth about our own complicity and begin to untangle the messy web of race and gender privileges that make it possible.

And, maybe our first action in response to injustice should be learning about the causes of the problem in the first place, and refusing to ignore, simplify, and whitewash them further.

Unjust Systems image via Dan Erlander.