In an interview this week with National Public Radio, Mohamed Elibiary described the kind of young disillusioned Muslims that he encounters in his security consulting work:

“I have never seen a female example here in the homegrown sphere here in the United States. There might’ve been a case but I haven’t read any literature or interacted with one. The men tend to be young males, late teenage to late 20s, and their personal life is kind of chaotic.”

Of the many things about the Tsarnaev brothers that will continue to be hashed out and mulled over by the media – their religion, their ethnicity, their national loyalties, their citizenship path, their access to bomb recipes, their relationship to each other – one thing that won’t get enough attention is their gender.

Of the many things about the Tsarnaev brothers that will continue to be hashed out and mulled over by the media – their religion, their ethnicity, their national loyalties, their citizenship path, their access to bomb recipes, their relationship to each other – one thing that won’t get enough attention is their gender.

And the fact that almost every single one of the mass shootings, terrorist attacks, or attempted acts of terrorism that have consumed our attention in recent decades has been committed by men.

Even the issue of race has been addressed head-on by writers like Tim Wise and David Sirota, who points out:

However, white male privilege means white men are not collectively denigrated/targeted for those shootings — even though most come at the hands of white dudes.

Likewise, in the context of terrorist attacks, such privilege means white non-Islamic terrorists are typically portrayed not as representative of whole groups or ideologies, but as “lone wolf” threats to be dealt with as isolated law enforcement matters. Meanwhile, non-white or developing-world terrorism suspects are often reflexively portrayed as representative of larger conspiracies, ideologies and religions that must be dealt with as systemic threats — the kind potentially requiring everything from law enforcement action to military operations to civil liberties legislation to foreign policy shifts.

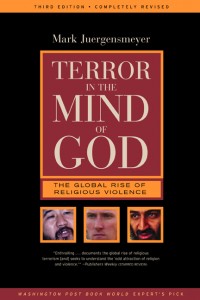

The best discussion of the particularly gendered nature of public violence comes from sociologist Mark Juergensmeyer.  His book, Terror in the Mind of God, focuses on multiple case studies of religious violence in five of the world’s major religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Sikh, and Aum Shinrikyo’s Buddhism.

His book, Terror in the Mind of God, focuses on multiple case studies of religious violence in five of the world’s major religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Sikh, and Aum Shinrikyo’s Buddhism.

While his analysis of the features of religious violence is complex and compelling, I think that what he says starting on page 198 about “why guys throw bombs” applies not only to the global religious violence he studied, but also to mass shootings like Adam Lanza’s in Newtown, James Holmes’ in Aurora, Jared Loughner’s in Tucson, as well as the domestic bombings we have seen in recent decades like those planned or carried out by the Tsarnaev brothers in Boston, Timothy McVeigh & Terry Nichols in Oklahoma City, Eric Rudolph in Atlanta, or Ted Kascinzki.

“Terrorist acts, then, can be forms of symbolic empowerment for men whose traditional sexual roles – their very manhood – is perceived to be at stake.”

Juergensmeyer ties the public and political acts of violence to the social construction of masculinity, which allows frustration to be expressed only through rage and anger. Especially in the midst of decades of social change around norms related to gender and sexuality, male fear of a loss of place is real. Fears of a loss of control and power, anxiety about shifting identities and social expectations, lack of ability to appropriately engage emotions and bond with other men as well as women … all of these things contribute to the stew of localized circumstances that led to each of the instances of violence Juergensmeyer profiles.

“These are fears not only of sexual impotence, but of governments role in the process of emasculation. Men who harbor such fears protect themselves … by attempting to reassert control in a world that they fear has gone morally and politically askew.”

Situate all of this in a violent culture, what even Bob Costas dared to call out in the aftermath of NFL player Jovan Belcher’s public suicide after he shot and murdered his girlfriend, and we have one more horrible tragedy from which to recover nationally.

One of my students asked me this week whether I think that the Tsarnaev brothers were motivated by their religion. I said we don’t know yet, but that I didn’t think so. I told her that I think there was something else going on with these two, and I know that Islam does not condone the kind of violence they carried out.

Over at Religion Dispatches this week, Juergensmeyer reaffirms his own analysis on these points:

“Though the details of the background and motives of the Tsarnaev brothers aren’t entirely clear, religion in the Boston bomber case also seems to be a secondary aspect of their motivations. Like the other cases in recent years, it is an expression of the rage of angry young men.”

Why did they do what they did? I don’t know.

But I do know that we need to talk more about the crisis of disillusioned masculinity that keeps growing and getting more dangerous every year.

If you’re interested in reading more about men and masculinity:

Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men, by Michael Kimmel

The Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and How All Men Can Help, by Jackson Katz

Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities, by Mark Anthony Neal

Manhood in America: A Cultural History, by Michael Kimmel

Masculinities, by R.W. Connell

Gun culture image via.