Last week I attended the Association for Interdisciplinary Studies and presented with a colleague about some of our work teaching a first year learning community as part of our institution’s general education program. Here are excerpts from my part, focusing on food and faith, diversity and service:

While teaching a religion & literature course last fall, I realized how many of the six memoirs we were reading mentioned or even centered around food as identity marker.

While teaching a religion & literature course last fall, I realized how many of the six memoirs we were reading mentioned or even centered around food as identity marker.

This isn’t an accident: In most major religions, food is a central marker of identity, from dietary restrictions to sacred ritual itself. It is where and when the world is ingested into the body, demanding respect and care in the case of Jewish kosher or Muslim halal butchering, or the prohibition of animal products altogether in the case of Buddhist vegetarianism, or where the substance of the food is transformed and the divine itself becomes a part of the believer, in the case of the Christian eucharist. Beliefs and practices related to food are indicators of theological and ethical commitments of a religion and of an individual believer.

At the same time, I have a colleague who has taught an English course on the rhetoric of the edible in several variations. She also collaborated to lead an international study experience on food and culture in central Europe this past summer. Our partnership, linking her composition course with my religion course, seemed inevitable.

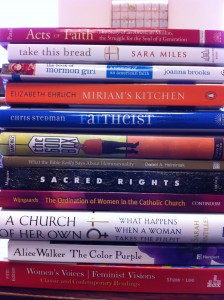

I titled the First Year Seminar I’m teaching now “Food, Faith, and Justice in Autobiographies.” It’s a religion course and the texts are: Acts of Faith, by Muslim Eboo Patel, Take this Bread by Episcopalian Sara Miles, Miriam’s Kitchen by Jewish Elizabeth Ehrlich, The Book of Mormon Girl by Joanna Brooks, and Faitheist, by Chris Stedman, Assistant Humanist Chaplain at Harvard. With each text, I include a session of basic instruction on the religion itself: key moments in the history of each religion, key terminology, significant figures, central beliefs. One goal is that by the end of this course, students will be familiar in a basic way with five distinct traditions.

This is crucial in part because rates of religious illiteracy are amazingly low in a country which is one of the most religious in the world. In 2007, USAToday proclaimed that “Americans Get an F in Religion.” There are several statistics that illustrate the problem: of 1,000 high schoolers surveyed, only 36% know that Ramadan is the Islamic holy month, and 17% think it is the Jewish day of atonement. 60% of Americans can’t name five of the ten commandments, and half of high school seniors think that Sodom and Gomorrah were married.

One required element of Illinois College’s BLUEprint general education program is U.S. diversity and global awareness, and while all first year students are introduced to basic diversity issues in every seminar, I chose to make religious diversity a focus in my seminar by bringing in texts from five different traditions.

One required element of Illinois College’s BLUEprint general education program is U.S. diversity and global awareness, and while all first year students are introduced to basic diversity issues in every seminar, I chose to make religious diversity a focus in my seminar by bringing in texts from five different traditions.

Seeing that there are shared values and journeys between Muslims, Jews, atheists, Episcopalians, and Mormons is foundational. Not only are my students being introduced to information about religions, through personal stories they are invited to see how human identity takes shape. In the first year, the first semester of college, the questions of who am I?, where do I come from?, where am I going?, and, why? … are central questions. These texts give students multiple viewpoints, five diverse and thoughtful companions for the discernment process in which they are enmeshed. It’s not about who is right and wrong. It’s about the process of learning and discerning.

On service:

Because the ability to understand and address social problems is essential for a 21st century college graduate, every Illinois College student in every first year seminar is required to participate in a one-day service blitz, read Adam Davis’ article on “What We Don’t Talk About When We Don’t Talk About Service,” and engage in reflection on the experience. I amplified this focus on service in my seminar, in part based on Sara Miles’ story. Because the eucharist is central to her experience of becoming Christian, she started a food pantry at her church, and eventually expanded her work to start and sustain more than a dozen pantries in the San Francisco bay area. For her this is a religious activity, following the instruction from Jesus to “feed my sheep.”

Students in my seminar each served in one of three local nonprofit agencies’ food programs: The Food Center (a local food bank), New Directions (a homeless shelter that serves an evening meal), and the Jacksonville Congregational Church’s weekend sack lunch program, serving all those in need.  Students went with a partner or small group at least three times to their assigned location, did basic research on the agency and the issue on which it focuses (children , the elderly, homeless, etc.), and then wrote a reflection paper and did a group presentation on their experiences.

Students went with a partner or small group at least three times to their assigned location, did basic research on the agency and the issue on which it focuses (children , the elderly, homeless, etc.), and then wrote a reflection paper and did a group presentation on their experiences.

This assignment and project integrated the arts and sciences by using spiritual memoir as opportunity to talk about sociological realities. It integrated the college experience with the local community by making three hours of off-campus service required for a course grade. It encouraged students to consider their role in the world, and put into practice something we read about for class discussion. It puts students in the middle of a basic social problem: poverty and food access. And it embodied multiple components of the BLUEprint, civic engagement, U.S. diversity, social and spiritual issues, and requiring that the students use and develop skills like critical thinking, writing, collaboration, and speaking.

More importantly, students were transformed. In attitude, from thinking that the people at the church were judgmental to appreciating what they do to help hungry people, and in action by sustaining the commitment to show up and volunteer even after the required hours were over.

We did a lot of cool stuff with our learning community this fall. To read about our HairRaising service experience, click here.