Many good people live and work at the intersections … of feminism and Christianity, of ministry and justice, of religion and politics, of gender and society, of race and inequality, of everything and then some. I’ve invited a few people to tell a story from their intersections, and will be sharing their stories from time to time here.

Today’s piece comes from Mary Beth Fraser Connolly, Assistant Director of the Lilly Fellows Program in Humanities and the Arts and instructor at Valparaiso University. She is also the author of the forthcoming book, Women of Faith, which she talks about here:

In 2006, I was hired to research and write the Chicago Sisters of Mercy’s history. The result of the project, Women of Faith: The Chicago Sisters of Mercy and the Evolution of a Religious Community, will come out in February 2014 from Fordham University Press. In the early days of the project, the Mercy editorial committee and I kicked around some titles until we landed upon one that ultimately was rejected by Fordham. We had everything from The Fourth Vow (the Sisters of Mercy unofficially have a fourth vow to service to women and children), to Response to Need, and to Led by Mercy. One should not underestimate the importance of a good title and Women of Faith works. Oddly enough the rejected titles may not work for bookselling or library cataloging, but they are not off the mark – thematically. Response to Need was particularly meaningful to me as I dove into the archives and attempted to pull together a thread or narrative of the Chicago Sisters of Mercy history from 1846 to 2008.

In 2006, I was hired to research and write the Chicago Sisters of Mercy’s history. The result of the project, Women of Faith: The Chicago Sisters of Mercy and the Evolution of a Religious Community, will come out in February 2014 from Fordham University Press. In the early days of the project, the Mercy editorial committee and I kicked around some titles until we landed upon one that ultimately was rejected by Fordham. We had everything from The Fourth Vow (the Sisters of Mercy unofficially have a fourth vow to service to women and children), to Response to Need, and to Led by Mercy. One should not underestimate the importance of a good title and Women of Faith works. Oddly enough the rejected titles may not work for bookselling or library cataloging, but they are not off the mark – thematically. Response to Need was particularly meaningful to me as I dove into the archives and attempted to pull together a thread or narrative of the Chicago Sisters of Mercy history from 1846 to 2008.

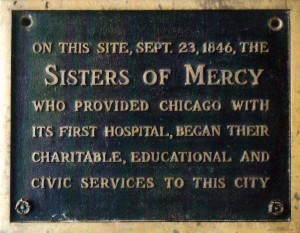

When I talk about the Chicago Sisters of Mercy, I mean the women of this regional community comprised of eight separate foundations, spanning from Chicago to Iowa City to Milwaukee and points in between. They had hospitals, academy schools for girls, parish schools for boys and girls, and a women’s college. Mercy Hospital Chicago and Iowa City, Saint Xavier University, and Mother McAuley High School in Chicago are still in operation, though not owned directly by the community. The Chicago Mercys’ history is long and finding that thread – that narrative – to make Women of Faith a manageable text was at times challenging. Response to Need kept coming to my mind. The Mercys were responding to a need, in 1846 and through 2008. They are still doing it today.

The sisters both past and present were with me, floating about my brain as I thought about how to be respectful and honest about their history. I must confess I am sympathetic to the history of women religious like the Chicago Mercys. I like them. I could give you a list a mile long as to why I do, but I recognize that there are many who have hard feelings about their time in Catholic parochial schools and can share a story or two about the demon nun who terrorized her students. It’s a complex history. Sometimes, however, the stories are straightforward examples of women who buoyed by their faith in God and the support of their sisters in community responded to a need regardless of the consequences.

One example I keep coming back to is that of Mother Agatha O’Brien, the first Reverend Mother of the Chicago South foundation. She entered the Sisters of Mercy in Ireland at sixteen as a lay sister, because she had a rudimentary education and no dowry. Lay sisters tended to be responsible for domestic duties and did not have the same status and voting rights as choir sisters, who brought dowries and had better educations. When the first Sisters of Mercy came to the United States to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1843, O’Brien went too as novice. O’Brien made her full profession as a choir sister right before a second foundation in Chicago was made. Her talents had elevated her in the eyes of her superiors and she was chosen to lead the new foundation, which consisted of four other sisters. O’Brien was only twenty-four. Under her leadership, the community opened a female academy, a handful of parish schools for poor immigrant children, and took over the only hospital in Chicago by 1852.

In these years, Chicago faced deadly cholera epidemics, usually hitting in the summer. In the summer of 1854, a cholera epidemic claimed the life of Mother Agatha O’Brien. She walked into a cholera ward in early July and the next day she died. Cholera was and is a terrible sickness. In the 1850s in Chicago, it was very deadly and the sister-nurses who operated Mercy Hospital knew this.

That month, the Mercys lost three other sisters and a parish priest to cholera. Why would anyone walk into a cholera ward, knowing they could contract the disease and die? Why did Mother Agatha? We could say she was a fool, or maybe she thought she was immune – it wasn’t the first cholera epidemic after all. Was she determined to help her fellow countrymen, the immigrant Irish, as she was also an ardent champion of a free Ireland? Maybe she was swept up in a romantic notion of religious life and dying in the course of her duty would be glorious? Maybe her faith in God carried her into that ward? Or was it her dedication to the charism of the Sisters of Mercy, her community’s foundress Catherine McAuley, and the vows she professed “to serve the poor, sick, and ignorant?” (The Mercys use “uneducated” these days.) There was a need, and Mother Agatha and her sisters in religion filled it.

This is a dramatic example and it is very easy to accept as an example of a good religious sister. Heck, she died while serving the poor and sick! There are other stories like this one – maybe not so deadly, but dramatic nonetheless. Other types of stories abound of sisters negotiating episcopal authority to achieve what they wanted. Reverend Bishop said no, the sisters found a way around him. The Mercys saw a need, they filled it. It is easy to admire these women for their strength, their championing of the poor, of women and children, in the face of patriarchal authority.

We all like a good story and in the light of recent news of Nuns on the Bus, Network, and LCWR, seeing mature women of faith standing up to male authority – both ecclesial and state – it is very, well, satisfying. Look there; see how the good sisters are leading the way? Yes, we like that. Over the course of my research and writing, while compelled by the drama, I also marveled at the consistent presence of the Sisters of Mercy and how they keep faith with their founding charism. The sisters, who fed their students, gave them clothes, visited neighborhoods, nursed, taught, and spent time with those needing an ear, or a shoulder, did so without cameras and newspaper reporters. They don’t do it now for the press or accolades, but they are smart, savvy women who know how best to reach people and to respond to need where they see it. These are human women, not perfect, but human faithful women, dedicated to God, their church, their neighbors, and each other.

We all like a good story and in the light of recent news of Nuns on the Bus, Network, and LCWR, seeing mature women of faith standing up to male authority – both ecclesial and state – it is very, well, satisfying. Look there; see how the good sisters are leading the way? Yes, we like that. Over the course of my research and writing, while compelled by the drama, I also marveled at the consistent presence of the Sisters of Mercy and how they keep faith with their founding charism. The sisters, who fed their students, gave them clothes, visited neighborhoods, nursed, taught, and spent time with those needing an ear, or a shoulder, did so without cameras and newspaper reporters. They don’t do it now for the press or accolades, but they are smart, savvy women who know how best to reach people and to respond to need where they see it. These are human women, not perfect, but human faithful women, dedicated to God, their church, their neighbors, and each other.

Yes, I like these Sisters of Mercy, these women of faith.