In the song “The Silence of God,” Andrew Peterson sings:

It’s enough to drive a man crazy, it’ll break a man’s faith

It’s enough to make him wonder, if he’s ever been sane

When… Heaven’s only answer is the silence of God

It’ll shake a man’s timbers when he loses his heart

When he has to remember what broke him apart

When the crying fields are frozen by the silence of God…

What about the times when even followers get lost?

‘Cause we all get lost sometimes.

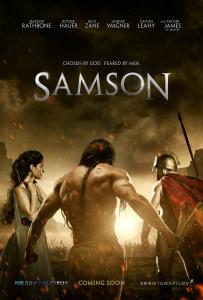

Martin Scorsese’s new film Silence (2016) is about followers who get lost. Based on Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel of the same title, and reminiscent in theme of Ingmar Bergman’s film Winter Light from his 1960’s “Silence Trilogy,” it is easy to see it as a personal statement from Scorsese, both because he spent 25 years trying to get this film made and because he’s essentially said as much in interviews.

In the film, two Portuguese Jesuit priests, Father Rodrigues and Father Garrpe, travel to Japan to investigate reports that their mentor, Father Ferreira, has committed apostasy, denying Christ. When they arrive, they realize the situation for Christians is worse than they imagined, Christianity having recently become illegal in Japan, with inquisitors roaming the towns and villages, looking for converts to either apostatize or be killed. The priests find many Christians who are practicing their faith in secret, and the hardest part of watching the film is watching some of them be tortured and killed for their faith.

Shusaku Endo was both Japanese and a committed Catholic Christian. His novel is a complicated one, as he seems to be pointing out the hazards of Western Imperialism as well as of cultural relativism. He is dangerously honest about the doubts and weaknesses of believers in God, and about the reality that God often does not speak in ways that are easily discerned. While many Christians have found hope in Endo’s novel, and the film’s ‘God’s-eye’ point of view shots imply the presence and providence of God, it certainly does not follow the formula of most modern-day Christian novels (or films) where the protagonist must have an overwhelming encounter with Jesus and end up with a stronger faith at the end of the story than at the beginning.

I believe that Endo’s novel and Scorsese’s film are actually a wonderful balance to Western triumphal Christianity. Jesus rose victorious from the grave, but He also suffered throughout His life as the “man of sorrows.” Churches, in America particularly, are quick to tout the benefits of following Christ, often promising health, wealth, and a deliverance from evil, but are much slower to present the challenges of following Christ, reminding their followers that to follow Jesus is to take up your cross, the instrument of torture and death. Endo and Scorsese will not settle for a truncated Christology; they want to know Christ “and the power of his resurrection, [that they] may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death” (Philippians 3:10, emphasis mine).

What interests me the most about Silence is the idea that religion is culturally specific. To put it in question form, are certain people groups and cultures predisposed to only accept certain ideas about God? Or, is that selling people short and, more importantly, selling short the truth and the ability of God to communicate with His creation? Of course, one’s answer is invariably bound up with one’s view of whether there is a God and whether He takes part in the affairs of humans.

Christianity has often been seen as an “imported religion” from the West to the East. In Silence, the priests are told that the Japanese cannot understand the gospel of Jesus and that their religion will never take root because Japan is a swamp, able to nourish Buddhist faith but unable to nourish faith in Christ.

Now, I imagine everyone would agree that different cultures have different value systems and so specific religions fit more naturally and comfortably with specific cultures. But, the other thing to recognize is that the idea that religious truth is not applicable in certain times and certain places is a mostly modern, Western idea. Members of the world’s main religions do not believe that there are cultural boundaries on truth, and it is infuriating to them to be told that their doctrine doesn’t apply in certain places. It is mainly cultural relativists who want to prevent the spread of certain religions; traditional religious people believe that all truth is God’s truth and that if their religion is true in the West, it will be just as true in the East (and vice-versa), however many cultural obstacles it has to overcome or accommodate itself to.

Christianity teaches that Jesus is the true light that enlightens the whole world, but how even Jesus “came to his own [Israel], and his own people did not receive him.” (John 1:9-11), and how He sent His disciples out “to make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey all that I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:19-20). The apostle Paul, in Romans 1, writes about how God reveals Himself to all people everywhere, “For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.”

The early Christians looked into the unique cultural beliefs of a people group to see where God had planted His truth. When Paul preached to the Jews, he quoted their Scripture, when he preached to Gentiles, he referred to their understanding of the world and even to the philosophy found in their art. The Greeks had a philosophy of a divine principle that under-girded the universe, that they called the logos. The apostle John showed them how Jesus is the true logos of God.

Wise missionaries through the ages have also looked for clues about Jesus in different cultures. Scandinavian missionaries to the Santal people of India in the 19th century found that, while their practice of worshiping many gods was common, they all knew about a tradition among their people of Thakur Jiu, the Genuine God, who created all things, including the first man and woman who were deceived by Satan and realized that they were naked and ashamed. Don Richardson, in his book Eternity In Their Hearts, writes how the missionaries “found themselves with literally thousands of Santal inquirers begging to learn how they could be reconciled to Thakur Jiu through Jesus Christ.” Richardson also tells about living among the Sawi tribe in New Guinea and learning of an unusual custom: “If a Sawi father offered his son to another group as a ‘Peace Child,’ not only were past grievances thereby settled, but also future instances of treachery were prevented… Since those days, approximately two-thirds of the Sawi people have, as they say, ‘laid their hands by faith upon God’s Peace Child Jesus Christ.’” The Dyak people of Borneo have a custom of taking two chickens, slaughtering one and sprinkling its blood on the shore of a river while tying the other one to a boat and placing their Dosaku (“my sin”) on the boat to be sent away. It doesn’t take much imagination to understand how God has placed on their hearts the need for forgiveness through the blood of another to take away their sins.

Church history shows how the Christian faith has taken root in the most diverse cultures (albeit not always spread with love as Jesus would have us do), starting in the Middle East and North Africa and moving to Europe, America, and Russia, and in the last century has spread like wildfire in China, Africa, and South America.

Endo himself saw how God has planted Himself in every culture. In his book A Life of Jesus, Endo writes that Japanese culture identifies with the “one who ‘suffers with us’ and who ‘allows for our weakness’… [so] I tried not so much to depict God in the father-image that tends to characterize Christianity, but rather to depict the kindhearted maternal aspect of God revealed to us in the personality of Jesus.” The very fact that the Japanese authorities in Silence are trying to enforce Buddhism on all Japanese people shows their view that what is true for some should be true for all (of course, it also shows how religion is used for political ends, but that is for another essay).

Jesus Himself gives only two alternatives in how we view Him when He proclaims that He is “the way, the truth, and the life, no one comes to the Father except through me.” Ultimately, either Jesus is Savior of all, or He is Savior of none. Either He is the genuine truth of God and the source of salvation for all people everywhere, or someone or something else is.

The reason Jesus is not just true, but the loving Savior we need, is found in the rest of the song that began this essay:

There’s a statue of Jesus on a monastery knoll

In the hills of Kentucky, all quiet and cold

And He’s kneeling in the garden… And He’s weeping all alone

And the man of all sorrows, He never forgot

What sorry is carried by the hearts that He bought

So when the questions dissolve into the silence of God

The aching may remain but the breaking does not

In the holy, lonesome echo of the silence of God.