Recent exchanges (starting with a comment on The Eviscerated Public Square piece) with a reader who describes himself as a lapsed Catholic who advocates a global spirituality spurned me to once again consider the impurity of Christianity.

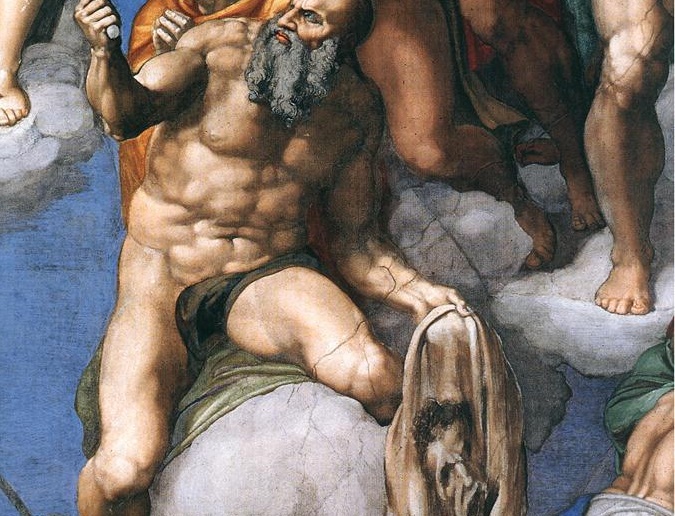

I’ve spent a considerable amount of time fighting the post-Reformation attempts to recover a pure Christianity shorn of papist additions. Reformation Day is only twenty-two days away, so maybe it’s time to enter the fray in the spirit of Rabelaisian Catholicism, Pagan-Folk Christianity, cocktail sipping, Greek-speaking spirituality?

The notion of a global spirituality does unhinge me a bit, because it presupposes that all the religions actually aim for the same thing differently. This is troublesome given how much the notion of religion has been taken apart by recent traditions as a construct that hamstrings living traditions by imposing vague general assumptions that ignore the real difference between them.

As this post about Remi Brague’s fascinating new book suggests, something is lost in papering over the differences between Christianity, Islam, and Judaism by throwing them all under the umbrella of monotheism and religions of the book.

There is a great charm to the Rabelaisian mess of distinctions that Brague makes, because they break up the overly tidy taxonomies of comparative religion. It’s equally disquieting to point out the commonalities between historical traditions. David Bentley Hart does this in his most recent book The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, and Bliss by riffing on the notion of God Aquinas labeled as ipsum esse subsistens (God as the transcendent source of being itself, rather than merely yet another being, albeit a really, really, really, big one, within the world):

‘Several of the religious cultures that we sometimes inaccurately characterize as “polytheistic” have traditionally insisted upon an absolute differentiation between the one transcendent Godhead from whom all being flows and the various “divine” beings who indwell and govern the heavens and the earth. Only the one God, says Swami Prabhavananda, speaking more or less for the whole of developed Vedantic and Bhaktic Hinduism, is “the uncreated”: “gods, though supernatural, belong … among the creatures. Like the Christian angels, they are much nearer to man than to God.”

Conversely, many creeds we correctly speak of as “monotheistic” embrace the very same distinction. The Adi Granth of the Sikhs, for instance, describes the One God as the creator of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. In truth, Prabhavananda’s comparison of the gods of India to Christianity’s angels is more apt than many modern Christians may realize.

Late Hellenistic pagan thought often tended to draw a clear demarcation between the one transcendent God (or, in Greek, ho theos, God with the definite article) and any particular or local god (any mere “inarticular” theos) who might superintend this or that people or nation or aspect of the natural world; at the same time, late Hellenistic Jews and Christians recognized a multitude of angelic “powers” and ,,principalities,” some obedient to the one transcendent God and some in rebellion, who governed the elements of nature and the peoples of the earth. To any impartial observer at the time, coming from some altogether different culture, the theological cosmos of a great deal of pagan “polytheism” would have seemed all but indistinguishable from that of a great deal of Jewish or Christian “monotheism.”

To speak of “God” properly, then -to use the word in a sense consonant with the teachings of orthodox Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, Hinduism, Baha’i, a great deal of antique paganism, and so forth -is to speak of the one infinite source of all that is: eternal, omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, untreated, uncaused, perfectly transcendent of all things and for that very reason absolutely immanent to all things.’ [Sorry, that was rather long, but I broke it up for you into paragraphs to make it easier to follow.]

So why not keep both the distinctions and commonalities together in productive mess? Hart provides you with the resources you need to explore the pole of particularity in a much more actively combative account of the uniqueness of Christianity in his Atheist Delusions.

It seems that global religious syncretism would iron out these creative tensions.

Monty Python on where conceiving God as yet another thing in the universe leads you:

While you’re at it, why not browse through the Cosmos TOP 10 Booklist archives?