The intersection of religion, the imagination, and science is a constant preoccupation of mine.

I believe this topic first became an obsession upon reading Czeslaw Milosz‘s The Land of Ulro. The poet’s book is one of those weird works that is way ahead of its time. It goes beyond all the prescribed literary boundaries. After having read it four or five times I still can’t tell whether it’s autobiography, literary criticism, philosophy of science, history, anthropology, theology, and so on. It is all of those things, even if the religious element predominates.

The Land Land of Ulro documents, rather haphazardly, in a very poetic fashion, the breakdown of the Western religious imagination on the heels of the first scientific revolution. Why was the first revolution so deadly? Because its mechanistic ideology meant that religion was banished to the realm of the human mind, the only sphere of freedom remaining in a mechanistic universe. A totally uniform universe also greatly challenged the three-tiered vision of the universe consisting in hell, earth, and heaven. The retreat into the haven of the mind also forced a turn to the subject, who was subsequently, to use Charles Taylor‘s neologism, disincarnated from the rest of reality (and later to love than usual).

Then again, it hasn’t all been a loss. It’s easy to fall into default narratives of decline, especially for Christians, ever since the Reformers of the 16th century put so much emphasis has been upon the purity (yeah right, read Paul between the lines!) of Early Christian communities. Here is a summary of what Larry Chapp had to say about the significant gains for theology in the modern period in an earlier interview I conducted with him on Cosmos:

1) The rapid expansion of our understanding of the universe’s size, which, as Thomas O’Meara argues, has implications for the doctrine of Incarnation.

2) The naturalization of the cosmos, or what Karsten Harries has called the homogenization of space.

3) The development of evolutionary thought and how it requires us to rethink our categories of causality much in the same way as the homogenization of space does.

4) All of these taken together require a rethinking of how we theologically conceive order and hierarchy. Larry alludes to Whitehead’s suggestion in Adventures of Ideas that perhaps beauty can be best understood as the ordering of novelty.

The Catholic theologian Oliver Davies, in his recent book, Theology of Transformation, builds a whole theology upon these insights and adds a new caveat. He believes that we are in the midst of a second scientific revolution. Here is what he thinks its hallmarks are and how they open up the door to an incarnationally-centered Christian imagination:

If the effects of the ‘first scientific revolution’ were to separate mind from matter, then the effects of the ‘second scientific revolution’ are to bring them back together again. For Newtonianism, matter was the domain of determinism and so a lack of freedom, while our subjectivity as mind was the privileged place of our freedom. We were free of the world by being in the deterministic world as self-aware subject who could exercise power over the world and its materiality through technology. According to this model, materiality as the field of determinism was either left behind by our spirit–through transcendence–or to be overcome by our spirit–through technology–in order that we (who are most properly spirit) should be free. Here there is a separation between who I am as spirit (or mind) and who I am as matter (or body). From a historical point of view, we can note also the extent to which the language of human spirit and divine Spirit have merged here, when each is defined as being in opposition to matter and the material.

But the effects of the scientific self-understanding which is emerging today are quite different. Here it is presupposed that we are materiality ‘all the way down.’ Neuroscience, genetics, and evolutionary biology show that mind and matter in us form a thoroughgoing continuity, each presupposing the other and each having causal effects upon the other within a continuum of human life as ‘intelligent embodiment’ in a material world. Quantum physics does so even more radically. Consequently, there is no point at which the mind can be ‘outside’ matter. We are free within materiality and not beyond it. Science is teaching us that we are both pure subjectivity and complex materiality at the same time. And in fact, there are no grounds for reducing one to the other (despite the best attempts of some). Our human truth, as ‘intelligent embodiment,’ is a paradoxical one and involves a simultaneity of matter and mind in us. We are not only in the world as subject but we are also far more of the world than we had thought. Indeed, we may need to think of ourselves even, first and foremost, as being world.

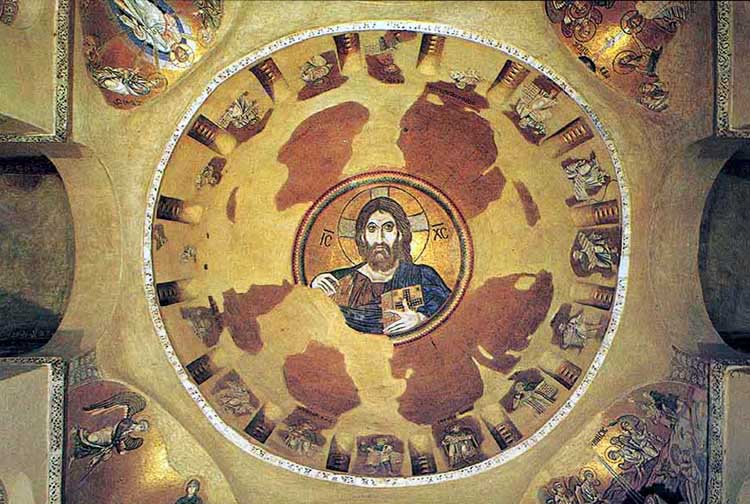

It is not difficult to see how Davies later makes the argument that our imagination of our place in the world, emerging from the second scientific revolution, is much better suited to the incarnational thrust of Christianity than the Manichean dualism of the first scientific revolution. The second revolution overcomes modernity’s pseudo-problem of connecting mind back to the world. It also opens up avenues for recovering a pre-modern cosmically-oriented Christianity (Think: Von Balthasar’s book on Maximus the Confessor).

Davies has started an exciting project in Theology of Transformation. I look forward to seeing how he develops these insights later in the book. I must say that this is one of the most exciting theology books I’ve read in a while and should probably be added to my list of TOP10 of theology books I’ve read in the last 10 years.

Admittedly, Theology of Transformation is a bit on the pricey side in its limited hardcover run, so you might want to explore the author’s other books on love/compassion, Meister Eckhart, and the Eucharist. All of them circle around some similar issues. Davies has his own (badly designed) website where you can learn more about his project. And if you want to explore similar avenues into the fruitful ongoing conversation between science and religion then look at this nearly comprehensive list of works in the field.