Yesterday we discussed Woody Allen as a liminal personality stuck somewhere between belief and disbelief. Being lukewarm is acceptable to most, even if it’s a bit hard on God’s stomach, but when one makes a jump into either committed belief or unbelief (from its opposite), then one becomes an outcast. There is nothing more frightening than the person who has betrayed a community to that community; bridges burn automatically behind them.

Being haunted by both belief and non-belief, a certain brand of late modern lukewarmness, is something that James K.A. Smith rightly presents as Charles Taylor’s definition of what it means to live in A Secular Age. A secular age, as Taylor understands it, is not synonymous with progress into unbelief, or the expunging of belief from the public square, because both trends have shown themselves to be easily reversible. Instead, a secular age is unique because of something else. Smith deftly summarizes this something else in his brief summary of Taylor’s book-brick in How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor:

Ours is a “secular age,” according to Taylor, not because of any index of religious participation (or lack thereof), but because of these sorts of manifestations of contested meaning [this comes after an extended discussion of Julian Barnes’ Nothing to Be Frightened Of and Elie’s The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage]. It’s as if the cathedrals are still standing, but their footings have been eroded. Conversely, the Nietzschean dream is alive and well, and the heirs of Bertrand Russell and Auguste Comte continue to beat their drums, and yet Oprah and Elizabeth Gilbert still make it to the best seller lists and the magic of Tolkien still captivates wide audiences. Even a late modern hero like Steve Jobs doesn’t conform to the [original] narrative of secularism [as the total eradication of religion].

In other words, the age is secular because the non-believers doubt their doubts. I would argue that what Taylor and Smith mean by “secularism” is much more frequently associated with the epistemological fluidity–for both believers and non-believers–of postmodernity. But too many books have been published with the word “postmodern” in the title, I guess.

This is a disturbing situation for all concerned. Woody Allen might have great theological insights, even though he might be, or might not be (nobody knows fully!), a bit of a dirtbag. On the other hand, there is also the example of Max Scheler, who was one of the most brilliant early phenomenologists. His thought lies at the foundation of the personalist and distributist currents that have floated Catholic theology since at least the middle of the last century. Scheler was a convert to Catholicism whose prose and personality drew people in to both phenomenology and the Church in droves. Just get a whiff of the following passage from his famous essay on the order of love, “Ordo Amoris” [from his Selected Philosophical Essays] and you can see why:

I find myself in an immeasurably vast world of sensible and spiritual objects which set my heart and passions in constant motion. I know that the objects I can recognize through perception and thought, as well as all that I will, choose, do, perform, and accomplish, depend on the play of this movement in my heart. It follows that any sort of rightness or falseness and perversity in my life and activity are determined by whether there is an objectively correct order of these stirrings of my love and hate, my inclination and disinclination, my many sided interest in the things of this world. It depends further on whether I can impress this ordo amoris on my inner moral tenor.

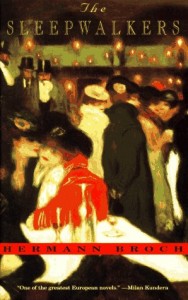

The play of this movement on Scheler’s heart fell to his womanizing perversities and he fell out of the Church toward the end of his relatively short life. The same fate befell Hermann Broch, another big convert to Catholicism, who penned what might be called the greatest Catholic novel, Sleepwalkers, that you know nothing about. I wonder whether such unfaithfulness in human relationships is also what makes Woody Allen waver so much in his faithfulness to atheism.

I think our period, with the breakdown of purely abstract philosophical and theological systems, has only come to highlight the necessary harmony between theory and practice for both believers and non-believers. Such a harmony is at the root of the Philokalia‘s teaching. It is something that I’ve discussed elsewhere under the heading of philosophy as a way of life.

The fact that Max Scheler was not able to impress the ordo amoris upon his moral inner tenor does not negate his philosophical and existential insight. On the contrary, the tragedy of his life only proves its reality for him and the rest of us.

It might also suggest that drastic conversions or reversions (always betrayals to some community) grow out of the small lukewarm betrayals that accumulate. I’m haunted by this thought as I finish typing this at around three in the morning when I know I have to take our eldest to preschool in five hours from now. Pray that I get up in time.