Another day, another year, another Halloween, and yet another Reformation Day. Today some of us remember the deeds of Martin Luther.

I like to harp on this, because it never really registers: Luther never meant to break away from the Catholic Church.

The act of nailing the 95 theses was not an unusually dramatic gesture. It was a traditional medieval practice to nail theological conundrums to cathedral doors in order to declare an open debate about them. The tradition was part of the medieval messiness and openness (forget all those myths about repressed and backwards medievals) that worries Douthat about the Francis Church–as if we can read how it will turn out so early into his tenure.

Staunch defenders of theological conservatism like to present themselves as defenders of the Church by recalling such figures as Catherine of Siena, Dante, or Chaucer. What they forget is how for every one of these figures who stayed within the fold there were at least ten others who took their well-meaning criticism of Rome and the pope to such an extreme that they caused schism, while Rome continued to sail on.

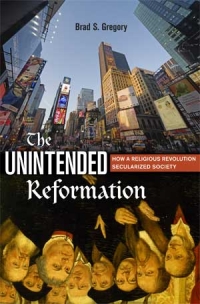

This is not to criticize the sincere objections and rightful criticisms of reformers. But frequently the solutions they proposed only compounded the earlier problems. This is the basic argument of Brad S. Gregory’s The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society. Here he comments on how the scripture-alone solution led to divisions within the Church:

The unintended problem created by the Reformation was therefore not simply a perpetuation of the inherited and still-present challenge of how to make human life more genuinely Christian, but also the new and compounding problem of how to know what true Christianity was. ‘Scripture alone’ was not a solution to this new problem, but its cause.

Brad S. Gregory follows the chain of the epistemological quandaries of the new reading of the Scriptures and the consequences of all the other Reformation “solae” all the way down to our present postmodern agnosticism and the political, economic, and environmental problems it causes.

I suppose this is why I was so puzzled by the recent debate about the Protestant Future sparked by the video below. It seems like a very odd thing to ask about the future of something that is not intentionally structured. On the other side of the aisle, there is something ignorant about Catholics talking about “the Protestants” as if they were all the same. It presupposes a level of unity that is in no way reflected in reality, even if unity was the original intention of the Reformers, much like present day conservative Catholic would-be reformers.

There is no one Protestantism. There are only Protestantisms.

Note how the panel is not representative of the diversity of Protestantisms, granted, reflecting it is an impossible task:

You might also be interested in taking a look at why Philip Jenkins, a Protestant scholar, appreciates Rome’s genius for absorbing dissent here.