I was recently reminded of a quip in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. His character says:

I was thrown out of college for cheating on the metaphysics exam; I looked into the soul of the boy sitting next to me.

I believe this episode of copying is fruitful for thinking about what so-called Western culture really is and is not.

The quip came back to me yesterday during Sam Rocha‘s Catholic Philosophy 101 lecture at the University of Washington’s Newman Center (part 2 comes next Wednesday 7PM) when religion scholar and Far East expert Justin Tse said “YESSS!” loudly and slammed down his fist.

Tse in turn reminded me of an episode Chesterton recounts. According to G.K. Aquinas was always digesting problems wherever he went; he never stopped thinking. One such episode involved a serious breach of etiquette. In the middle of dinner with the French king Aquinas said, “That’ll take care of the Albigensians!,” and slammed down his fist down on the dinner table sending plates flying. Nobody does that to the king, except for Aquinas. The king didn’t lose his cool and asked for someone to bring writing implements for the theologian.

The connection between these two events is somewhat odd, because it was occasioned by an anti-triumphalist statement made by Rocha. Sam was talking about Catholics coming out of their ghetto of fear: fear of postmodernism, fear of relativism, fear of the modern world, fear of people who think otherwise than they do. Sam gave Aquinas as a counterexample.

Aquinas bravely went against the established canons of his time by adopting not only Aristotle, but also some of the arguments of Jewish and Muslim thinkers who preserved Aristotle then transmitted him to back to the West after he mostly disappeared from the scene sometime in late antiquity.

Rocha’s conclusion from this historical fact was: The West has never been Western.

I believe he is correct.

His insight goes way beyond the one historical moment. Nearly all the cornerstones of what we think of as Western culture are borrowings from other, non-European cultures. Europe is a culture of creative plagiarism.

According to both Plato (think: Egyptians) and Walter Burkert’s The Orientalizing Revolution, Greek philosophy is a borrowing, rather than something that miraculously appeared in Greece without precedent. It should be much more obvious that the Judeo-Christian religious foundation of the West did not originate in the West.

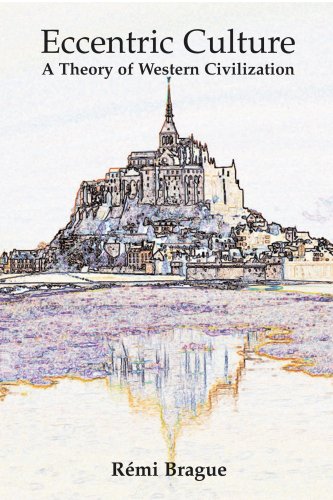

The book on all of this has, of course, already been written. Remi Brague lays out the non-Western sources of religion, philosophy, and many other inventions we think of as uniquely Western in his Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization. Brauge’s argument is that the core of the Western tradition lies in its continued borrowing and reshaping of non-Western traditions. In other words, the West is most West when it borrows from the non-Western. He calls this creative plagiarism “Roman” and its manifestations “Romanity.” Here is why:

To say that we are Roman is entirely the contrary of identifying ourselves with a prestigious ancestor. It is rather a divestiture, not a claim. It is to recognize that fundamentally we have invented nothing, but simply that we learned how to transmit a current come from higher up, without interrupting it, and all the while placing ourselves back in it.

This work of recognizing the higher and transmitting it is also internal, as when the Romans borrowed the borrowed concepts of Greece. This work of transmission and translation continues to this day in, for example, in Eastern Europe. If we look at only Poland then writers such as Czeslaw Milosz, Jozef Tischner, Gustaw Herling, Krzysztof Michalski, and Zbigniew Herbert made some of the most profound recent contributions to sifting through what is highest in Western culture while keeping a critically appreciative eye on the Russian East.

The “creative plagiarist” label for the West is not an insult. There is a certain humility in recognizing what is higher and adopting it.

Doesn’t Paul use the language of adoption to speak of our relationship with God? There is also a Trinitarian analogy here. I’m thinking of an argument Joseph Ratzinger makes, I believe in his Introduction to Christianity. He says something to the effect that the Fathers used and advanced Greek philosophy during the Trinitarian debates by positing “relation” as a substance, a kind of “substantive relation” as an ontological given; just as the persons of the Trinity are defined by their relations, so is the rest of reality. In other words, “No man is an island.”

I believe this is also part of what I mean as I’ve been groping towards while developing the concept of a messy and impure Rabelaisian Catholicism. Perhaps there are still things to learn from Islamic cultures, as some argued in the 19th century?

In other ways, although he would surely dispute this since he saw himself as working against the grain of Western thinking, the philosophy of the Other developed by Levinas in influential texts such as Otherwise than Being and Totality and Infinity is a classically Western form of thinking. I owe this last connection to Thomas Pfau’s pathbreaking work Minding the Modern. OK, now we’ve come full circle.

In conclusion, against Chasing Amy, I’d like to say there’s much to be said for tracing:

If you want to explore more about the relationship between philosophy and theology see the TOP10 list of my favorite philosophy books, my report on the return of religion to French philosophy, and my essay on St. Socrates and the Church Fathers.