What follows is a longread essay by Dariusz Karlowicz that appeared in his award-winning Polish-language collection entitled The End of Constantine’s Dream. The following translation is my own published with the author’s permission. Part II is now up right here.

Death as an Object of Faith: Meditation for Holy Saturday

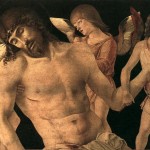

Holy Saturday: The drama of Holy Week dies down for a moment. But our thoughts race ahead, because they are hesitant about stopping near scenes of mourning, at physically repelling pietas, or by the corpse of Christ that has turned blue (as Mantegna saw it during a moment of religious dread). It is difficult to stay with a dead God, if only because his very death negates the logic of all consolations, doubt strikes not only the object of hope, but also its very possibility. We run away. Even though the tortured body of Christ rests in its grave, we live in the inevitable arrival of Sunday. The encouraging signs: rolled away stone, empty grave, angels, glory! It’s as if the final battle with the gates of hell is already behind us. But why does God wait nonetheless? Why does he leave us at the grave? Why is the One who is capable of rebuilding the temple in three days incapable of rebuilding it immediately?

The temptation to flee the silence of Holy Saturday is not new. These same waters—overflowing with disgust for the foolishness of an actual incarnation and an actual sacrifice—water the Docetist heresy. In the apocryphal Gospel of Bartholomew (dated back to the third century) the harrowing of hell occurs already on Friday before the deposition from the cross. However this only makes Christ’s tomb into a mere theatrical decoration, and Saturday a problem of rhetoric not philosophy. I believe that Irenaeus of Lyons, who thought the Savior was in hell from his death until his resurrection, has the backing of some weighty theological reasons. Saturday understood as the day when death’s hegemony is overcome can only be that from God’s perspective, but directly inaccessible to our knowledge. In order to accept it we must believe in the initial truth of Holy Saturday, in the limits to everything we call life. Also, this is most difficult, in the death of all human meaning and human hopes, in the death of the God whom we create in our own image and likeness. Easter is not a holiday of bunnies and Easter eggs. We will not pull ourselves up to the truth of the resurrection on our own. We have to accept the revelation of death and stand at the wall of the world’s ruin. Saturday is a time to meditate upon and prepare for death. Is this an exaggeration? Does this mean we have to believe in an abyss? Must we descend into the abyss? Die? “Amen, amen, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat but if it dies, it produces much fruit. Whoever loves his life loses it, and whoever hates his life in this world will preserve it for eternal life. Whoever serves me must follow me, and where I am, there also will my servant be. The Father will honor whoever serves me” (Jn. 12:24-26).

The Descent Into Hell

Greek stories of descents into hell were common enough to make some complain about traffic jams along the way to the ancient afterworld. The following figures descended into Hades: Dionysus, Orpheus, Hercules, Odysseus, and many, many others. The trope is typical enough to merit parodies such as the facetious Frogs of Aristophanes, or the mockery-packed tales of Lucian. We should leave behind the light embellishments of hellish curiosities and consider, in relation to Holy Saturday’s weight, what could have been the essence of these adventures. This will allow us to look at them as a reflection of God’s wisdom—a pagan praeparatio evangelica.

What strikes us about the ancient katabases is the continually returning theme of transformation, a complete rebirth of the person, a rebirth whose requisite is death. The Greek excursions to Hades are not excursions into hell in our understanding of the word. Hades is more an underworld rather than a place of punishment. Hades is what is located beyond the gate of life. And so an excursion to Hades is not so much a trip through a catalogue of tortures, it’s also not merely an opportunity to meet dead heroes, instead it can be understood as an image of total conversion and a witness to a purification from what people consider to be life, which is actually a form of death. “Who knows,” Plato quotes Euripides, “if life be not death and death life” (Gorgias 492e). Victory over death is a victory against oneself, against all that must die in order to make us capable of achieving perfection. This isn’t the only thread of these stories, but it might be the most interesting one for us today. Did it not appear in the myth of Persephone, which was part of the mysteries performed in Eleusis? Wasn’t Persephone the protectress of germinating grain? The grain which must die in order to live.

Let’s return to other Greek and Roman peregrinations. We’ll look at two variations—a successful journey and a failed one. The first variety is illustrated by Homer’s Odysseus who follows the advice of Circe and heads for the grove of Persephone to meet the shades of the dead. Virgil, with great poetic invention, will send his Aeneas on a similar voyage. The goal of both of these voyages is similar: knowledge. Odysseus heads into the underworld in order to find the shade of the renowned Tiresias, who can reveal the future to him. Anchises, the father of Aeneas, plays the same role in Virgil’s epic. In both instances life appears to be the realm of ignorance. Only death is capable of unveiling the truth to us. The truth that will show us the right path toward our goal. Life in the flesh turns us away from the truth. This same trope will resurface both in Plato and the spiritual masters of Christianity. The path to knowledge is a purgation of everything that’s a semblance of life. The path of an authentic philosopher is a preparation for death, practice in dying. “Other people may well be unaware that all who actually engage in philosophy aright are practicing nothing other than dying and being dead ,” (64a) says Plato in the Phaedo and he continues with, “the soul of the philosopher utterly disdains the body and flees from it” (65c-d). “Does he not agree with the divine apostle,” asks Clement of Alexandria, “0 wretched man that I am, who shall deliver me from this body of death?” (Stromata, III.18.2).

Perhaps we should read the story of Orpheus, whose quest to retrieve Eurydice ended in utter failure, in the same spirit? Even if his art was able to control Hades he wasn’t able to meet the demands placed upon him by the ruler of the realm of the dead. By looking back he demonstrated that he did not purify himself sufficiently, that his love was made of earthly stuff. Not everyone who descends into hell can be reborn, because not everyone who dies—dies in the philosophical sense of the word. According to Plato Orpheus should be counted as a Philomath, still attached to the body, not as a philosopher. His contempt for death did not have a philosophical motivation. The look back was a proof of bondage, which impeded the crossing of the spiritual world’s border. After all, what’s at stake is not a physical death, but rather a lasting spiritual transformation, that is, conversion—a word that Werner Jaeger notes was not invented by the Christians. “Even so this organ of knowledge must be turned around from the world of becoming together with the entire soul, like the scene-shifting periact in the theater, until the soul is able to endure the contemplation of essence and the brightest region of being… Of this very thing, then there might be an art, an art of the speediest and most effective shifting or conversion of the soul,” says Plato in the seventh book of The Republic (518c-d). Since authentic transformation is irreversible then it can be called the death of everything that does not belong to the spiritual realm. In Cyprian [of Carthage] the same interpretive move is made using the biblical story of Lot’s wife. Even though a different sort of conversion will be at stake here, even though the content and meaning of the transformation will be different, the principle that the one who is unable to die cannot really live will remain the same.

The guarantee of lasting happiness, argue the philosophers, its independence from fate, can only be guaranteed by a good totally independent from the caprices of fortune. There’s no need to explain how it has nothing to do with what universally passes as the good. At the source of the paradoxicality of philosophy lies the postulate of a lasting happiness, which is trailed, as if by a shadow, by a conviction about the fundamental caducity of the sensible world. The spiral of unsatisfied craving and the fear of loss are desires that throw their shadows upon every attempt at happiness that trusts in sensual goods. The philosopher turns away from them. He dies to them. The platonic definition of philosophy as preparing for death contains within itself an extremely meaningful metaphor. Life is the lapidary characteristic of all apparent goods. This is why the philosopher must pass for someone who is dead. For many his happiness will appear to be, as Calicles put it, the happiness of rocks and corpses. This is because, as Socrates will respond elsewhere, ordinary people do not understand what it means for a real philosopher to desire death, nor how they deserves this death, nor what sort of death is at stake (Phaedo 64b-c).

The descent into Hades in this life can therefore be read as a figure for philosophy—the art of transformation that leads men to perfection. Achilles, whom Odysseus meets in the land of the dead, is convinced that this meeting is greater than all of his own deeds (Odyssey, XI.485-486). It essentially is not an adventure for just anyone. Not fearing death, the courage to enter Hades in this life, is the best proof available to us of freedom from all the anxieties that ensnare the soul, in other words, of a complete transformation of one’s being and knowledge. This is why we ought to remember that what the philosophers call death is only one side of the transformation. It is the negative aspect of conversion, which at the same time glorifies what is best in man: the soul, reason, and virtue. Understanding death as a way of life will be totally deformed if we forget its positive dimension. Limiting oneself exclusively to the negative perspective reduces the notion of transformation to an absurdity. Both philosophers and later Christian theologians were not so much concerned with what we abandon, but where we are going and what we gain. Baptized into death (Rom. 6:3), conformed to Christ’s death (Phil. 3:10), living as those who have been brought from death to life (Rom. 6:13), we have passed from death into life (J. 5:24). As Seneca wrote, indifference to the verdicts of fate is not in itself a philosophical virtue. “Do you ask what it is that produces the wise man? That which produces a god” (Seneca, Letters from a Stoic 87:19), which refers directly to the Platonic definition of philosophy as a process of divinization. The longing after the Good is the cause of the desire, claimed Socrates in the Theatetus, to escape from the Earth into the other realm as quickly as possible. The escape is the process of likening oneself to the god as much as it is possible. “And to become like God is, he continues, “to become righteous and holy and wise” (176b). To understand how much Christians agreed with this message it is enough to mention that it was quoted in Clement of Alexandria’s Stromata nearly twenty times. We probably don’t need to explain that likening oneself to God is a call for Christians to imitate Christ—imitating him in his love, death and resurrection, which all are inseparable within the Christian teaching. St. Paul repeats the words of our Savior when he says, “You fool! That which you sow does not come to life unless it dies” (1 Cor. 15:36) . . .

I hope you learned as much from this reading as I did from translating it. To be continued . . .

. . . The second half of this essay is now available here.

Whatever else you might think of U2 this is one of the most stunning songs about the events reading to Christ’s death:

If you can’t wait until tomorrow, here are my many other posts related to Dariusz Karlowicz.

You can also now purchase my translations of Karlowicz’s The Archparadox of Death and Socrates and Other Saints.