The position of the Great Ormond Street Hospital, and the attending physicians, arises out of and flows from their determination regarding the futility of (further) treatment.

Charlie Gard is going to die.

The attending physicians at GOSH hold the proposed treatment in the US so highly unlikely to produce any appreciable improvement in the patient’s condition, that they refuse to participate on the grounds that they would be uselessly inflicting harm – in the form of pain, at least – on their patient: in essence, that they would be violating their oath as healers.

That is a serious matter.

Their determination is deserving of deference at least on par with that of the parents to pursue treatment for their son.

The courts were asked to resolve the dispute arising from these competing claims.

How they have done so has been satisfactory to exactly no one.

On the one hand, there is the apparent subtraction of parents’ rights, which are prior to the state and rooted in the natural law.

Those rights, however, are not absolute, though they arise out of precisely that duty to care, which primarily resides in the parents of minors, and only by delegation and derivation in other parties, including the state.

Both the doctors into whose care the parents have entrusted their child, and the state, of which the patient is a member, do nevertheless have real duties, with which come the corresponding powers to discharge them.

In the midst of all this, there is a crisis of confidence – one might even say a crisis of faith – in the medical profession, arising from the direction in which medical ethics throughout the West have turned.

In the midst of all this, there is a crisis of confidence – one might even say a crisis of faith – in the medical profession, arising from the direction in which medical ethics throughout the West have turned.

Essentially, the medical profession – sometimes under the pressure of politicians and bureaucrats, sometimes more pro-actively – has distanced its practice from the core conviction that life is a basic and irreducible good, to which patients have an inherent and inalienable right, which right must be defended at all costs and against every usurper – even the one who possesses the good, hence the right to it.

Nota bene: the right deserves protection at all costs: the good itself is perishable, and when the good itself, from which the right arises, is in precinct of expiry, there are inevitably hard decisions to make, which for their right making depend on the clear and cloudless vision of the goods at stake and of the rights that arise from those goods.

This is why the turn in the medical profession has created such consternation in Charlie Gard’s case and in many others.

That turn away from such clear and cloudless vision has already done grave harm, and will prove disastrous – even lethal, in the strict biological sense of the term – if it is not arrested and reversed.

I am not sanguine.

In any case, it seems to me that neither the decriers of the hospital, the physicians, and the state that has sided with them as the enemies of life and of the natural order, the protection of which is – on paper at least – their very raison d’etre, nor those who defend the hospital, the physicians, and the state, by ridiculing those with concerns and adopting a facile, “nothing to see here” attitude, contribute anything useful either to Charlie’s cause or to the broader public and civilizational conversation, which presses on us with ever more palpable urgency.

This is a hard case.

There are legitimate concerns on all sides.

Helpful consideration of those concerns requires that we be extremely reluctant to attribute evil intent, especially when there does exist the possibility of attributing the actions of agents and the positions of interlocutors to something other than malice.

On the other hand, vigilance is not only the price of liberty, but the necessary and prudent posture of every person and any people truly jealous of their own rights and those of their neighbors.

We all have friends on both sides of the Charlie Gard case, whose opinions we generally respect – even when we disagree with them – and whose character we know to be unimpeachable.

As we pursue this necessary conversation, let us be mindful of that.

Chris Altieri is the co-founder and General Manager of Vocaris Media. He hosts the flagship program of the Vocaris production arm, Thinking with the Church. He lives in Rome, Italy, with his wife and two children.

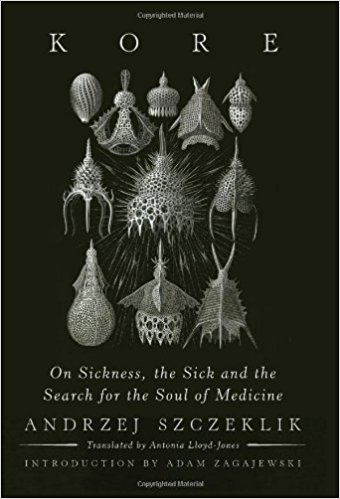

Suggested Reading: Kore: On Sickness, the Sick, and the Search for the Soul of Medicine

There is a grand tradition of physicians who are also great writers and philosophers. From Copernicus and Paracelsus, to Chekov, Osler and Frankl. And most recently Sherwin Nuland and Oliver Sacks have gained broad readerships and made huge contributions to the way we think and the way we live our lives. Andrzej Szczeklik is entirely worthy to join their company. When his first book, Catharsis, was published in English, critics from Seamus Heaney to Czeslaw Milosz stood to applaud. Now he has followed with an ever deeper and more accomplished book.

It has become unfortunately rare for a scientist or doctor to find his grounding in a broad understanding of literature and the humanities. But in Kore, the author insists that only with a curiosity thoroughly at home in both worlds can one expect to discover what we should mean about sickness and about the soul. No tedious academic, Szczeklik writes with the grace of a poet and the ease of a fine storyteller. Anecdotes drawn from a personal immersion in art, music, and literature are woven with reports on experimental medicine and daily clinical experience. From DNA and the re-creation of the Spanish Flu virus, to contemporary research in genetics, cancer, neurology, and the AIDS virus, from “Symptoms and Shadows,” to “Dying and Death,” to “Enchantment of Love,” every chapter of this book is alive and engaging. The result is a life-affirming work of science, philosophy, art, and spirituality.

If you like what you’ve read please make a donation to this blog through the button on the upper right side of this page to help keep it going.

Stay in touch! Like Cosmos the in Lost on Facebook: