Catholic History is stranger than you think.

[Léger] spoke to me with excitement about his disappointment with the doctrinal schemas: speculative theses that only repeat Vatican I and don’t consider the needs and possibilities of our time. We aren’t any longer at the time of the doctrinal liberalism of 1860 . . .

Marie-Dominique Chenu, Vatican II Notebook

Vatican II has been, since it was convened, the most controversial council in the history of the contemporary church.

Soft traditionalists, many of whom have an odd and anachronistic love of the free market, voice skepticism about its effect, if not its very essence. At best, it can be reconciled to the Church’s history as an afterthought; at worst, it requires damage control.

Hardline traditionalists, like the ill-named SSPX, walk a razor’s edge due to their unease with some of its decrees.

Sedevacantists go so far as to say it means the popes since the Council have forfeited their authority; in other words, the Chair of Peter is vacant. Common to all of these views is a political hermeneutic: Vatican II was, in some sense, a politically-motivated affair, devoted either to a direct or indirection erosion of tradition, a capitulation to Karl Rahner, the congress of Congars, and the playground of such clearly non-Catholic figures as Pope Benedict XVI. It was so bad that it now requires explaining away or repudiation.

But this view is wholly out of touch with tradition. In fact, the council often lauded by those who identify as “traditionalists” for its relationship with the great anti-Modernist, Blessed Pope Pius IX, as well as its general distaste for “Modernism.”

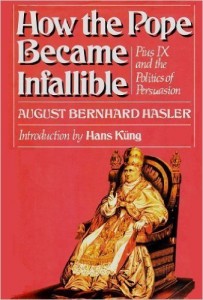

Vatican I, is demonstrably more political, less necessary, and generally harder to swallow than its successor. In his unfortunately under-read exposé of Vatican I (with a preface by Fr. Hans Küng of all people), Fr. August Bernhard Hasler, S.J. (a Vatican official with access to detailed records) argues that the Council was highly-political and little more than a rubberstamp for a highly authoritarian pope.

And, regardless, of one’s view of Pius IX, the Council did convene in a crazier period than the relative peace of its post-WWII successor. Pius was elected, and initially ruled, in sympathy with Europe’s rising liberal tendencies, but a number of terrorist attacks by Italian Nationalists led to a change of mind and a turn to the French for protection. Vatican I itself was interrupted (and essentially shutdown) by the Italian Nationalist conquest of Rome, leading to Pius’ identification as “captivus Vaticani.”

Furthermore, his attempts at defining papal infallibility met with resistance (here the relationship between Cardinals Newman and Manning is fascinating). Witness, this disturbing anecdote from Hasler’s How the Pope Became Infallible:

On June 18, 1870, emotions were running high in the great hall of the Council. A Dominican cardinal, Filippo Maria Guidi had come forward to speak against the pope and the Infallibilists (the first Roman prelate to do so), emphatically stating that the pope was not infallible in and of himself, independent of the Church, but only insofar as he reflected the views of the bishops and the tradition of the Church…That very evening Pius IX had Cardinal Guidi called in and bitterly castigated him for his speech. In reply to Guidi’s protest that he had only spoken as a witness to tradition, the pope snapped back at him with the oft-repeated phrase, “I am tradition.”

Pastor Aeternus, which defined papal infallibility, retroactively made unassailable Pius’s earlier proclamation on the Immaculate Conception of Mary (an action which might’ve upset St. Thomas Aquinas, whose epigones proliferated following Vatican I, and who had the honor of being depicted in a mural alongside Jesus and Pius, celebrating the Council). In some ways, this council (or, at least Pastor Aeternus) begins to look a bit like a modern Unam Sanctam, though more clearly delineated and with an even more transparent political context.

Up to this point, no one has tried to use Pastor Aeternus retroactively to force Unam Sanctam on us all. Deo gratias!