For the councils of the church, politics is traditional.

After Vatican Council II, many people have argued that, among other problems with the council, it was too political, causing its outcome to be suspect.

For a long time, I have said it is the reverse: if it weren’t so overtly political, it would be so unusual, so un-traditional, it would raise the question of its status as an ecumenical council.

This is not to say the councils are about politics, but rather, we must understand that the councils work in the real world, a world of politics. They get into the dirt because they take place in history, tainted as it is, with the effects of sin. Indeed, the very first council, the Council of Jerusalem, shows that even the earliest church was filled with prideful leaders and egos contesting against one another (cf. Acts 15). The first great ecumenical council, Nicea, certainly showed such intrigue as well –according to tradition, St. Nicholas decked Arius, and was thrown in jail by St. Constantine for it.

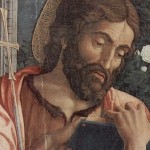

But, be it as it may, it is with St. Cyril of Alexandria, and Ephesus, where politics can be shown to be front and center with the theological debate. We see an Empress, St. Pulcheria, promoting the title of Theotokos, in part as a way to promote her own political power, to be reprimanded by Nestorius, causing in turn, the great fight on the person of Jesus Christ. St. Cyril of Alexandria used St. Pulcheria and her position as a way to make sure the Council of Ephesus went his way – and in doing so, he was able to get the council started before those who opposed him were able to get there, and he was able to use his power to prevent their attendance.

In turn, there was another council made by Nestorius’ supporters, which condemned Cyril, and was approved (for the time being) by the emperor, Theodosius II, causing St. Cyril to be thrown into exile. St. Cyril, however, would have none of it – he bribed officials and had a mob violently attack the palace, leading Theodosius to give in and affirm Ephesus against the supporters of Nestorius. Behind the scenes, all sides could be shown to be involved with all kinds of bribery. It was, by this time, expected by church officials in order to appease the government and get their support in councils. Indeed, it was so customary by this time, that St. Cyril’s Letters talk about customary gifts to government officials without any irony being shown in doing so (See St. Cyril of Alexandria’s Letters, FAC77; 94.1; 96.10).

Click here to keep reading about the political and Christological contributions of Emperor Justinian.