However, this vision of the state, which efficiently pacifies conflicts, is not free from simplifications and weaknesses. In the framework of modern political organisms one can also easily indicate phenomena which testify to the significant presence or even the expansion of elements of the fundamentalist state. “The Achilles heel” of the model of a minimum state is the problem of power. The actual situation in the state – whether pluralism of beliefs is respected in a society which is ethically divided, or whether an ethical crusade is conducted – is decided by the individual who is in possession of that power. It is the ruler who introduces and guarantees the new order, neutralising with his power the claims of individual ethical communities; it is he who is the causative power capable of maintaining, but also of destroying the established order. The ruler plays here a role which is incomparable with that of other members of the state community – he fulfils the function of a demiurge, ‘an earthly god’. This is why the model of the state of ethical minimum can function efficiently only when its ruler adopts the approach of a political ascetic; someone who in the sphere of politics is capable of rising above his own human conditioning – including above his own ethical conviction – and whose main aim is to care about maintaining the just principles of peaceful co-existence.

Such an approach, which requires a particular intellectual and moral predisposition of ruling people, appears possible in individual cases[2], however it is difficult to expect this on a mass scale. Therefore, with the spread of democratic ideas the problem immediately takes on an additional complication.

The demand to introduce democratic governments, although it appeared in the modern world relatively late, was only a logical consequence of the recognition of the autonomy of the individual as the foundation of social order. Everybody who, in the framework of the state of law is guaranteed autonomy in the private sphere, could also rightly demand the right to jointly decide about the future of the political community. When the modern state finally formed as a democratic state of law, it turned out that this apparently uniform connection of democracy and state of law contains a serious source of conflict. Modern political organisms function on the basis of two forms of legitimacy which, although they originate from the same axiological foundation – the moral autonomy of the individual – differ from each other significantly. The first of these, the principle of the state of law, places a barrier against the expansive claims of various ethical communities and legitimises only those institutions and actions of the state which guard elementary rights of man. The second recognises exclusively those institutions and actions which have obtained democratic legitimisation, expressed by a majority vote of citizens. An obvious dilemma arises: what will happen if, while fully respecting democratic procedures, a majority of citizens agree to suspend the principles of the state of law and replace them with the logic of a fundamentalist state which imposes a system of values held by the majority, and so the minority faces the alternative: conversion or elimination? The fact that such a situation in conditions of modern democracy is in every respect possible was shown by the events of the last century, the century of totalitarian systems. In this respect, the history of the peaceful and legal takeover of power by Hitler gives more food for thought than the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks in crisis-ridden Russia.

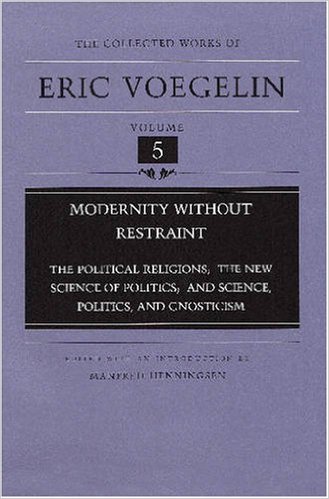

The treatment of totalitarian systems as a particular type of fundamentalist state seems in this case entirely justified. The similarity of totalitarian ideology to religion was noticed almost at once; it is enough to recall the classic work of Eric Voegelin, The Political Religions [3]. A separate and key question, which, however, it is not possible to consider in detail here, is the particular ethos of followers of totalitarian ‘religion’. Their specific system of values seems to be completely empty in content and appears to be reduced to one idea, the desire to participate in unlimited absolute power[4].

The lesson to be drawn from the appearance of totalitarian regimes is clear: respect for elementary rights of man as a necessary condition for autonomy, is much more important than the right to participate in power, which is based on the same principle of autonomy. In other words – the principle of the state of law is more fundamental than the principle of democracy and must restrict it. In accordance with this idea, in modern constitutional theory and practice, there have appeared solutions which aim to prevent a possible ‘dictatorship of the majority’, at least such, which require a qualified majority in order to change the legal standards guaranteeing fundamental rights of man. Such types of ‘quantitative’ restrictions certainly make it more difficult for ‘totalitarian democracy’[5] to arise, however they cannot definitely exclude it.

Without engaging in the dispute on whether democracy is the victim of the totalitarian system or its midwife, let us leave totalitarianism aside as the extreme example of the specifically understood fundamentalist state. The problems of the democratic state of law itself and the internal processes underway inside it seem much more interesting. Let us have a look at what influence the principle of democracy has on the functioning of the ‘state of ethical minimum’.

The introduction of the democratic constitution in the framework of the modern state signifies that individuals who identified themselves with specific ethical communities and who could safely realise their values in the private sphere, now obtain access to and are able to influence state politics. As fully entitled members of the political community they may fill it out with their own ethos. The state – the external neutral power which was supposed to keep peace between different ethical communities and with its strength, safeguard individual rights – once again becomes an arena of ethical conflicts. While the whole sense of the minimal state was reduced to the separation of various ethical communities from each other and depriving them of the possibility to influence the political authorities – and therefore, as it were, to their ‘privatisation’ – in the democratic system their politicisation takes place once again and results in the ‘ethicization’ of the state. An area appears which is common for all, where a multitude of value systems immediately engage in the same sharp and irresolvable conflict which centuries ago led to religious wars. However, this happens within the framework of the structures of the state of law, which tames and institutionalises the conflict[6].

The area of struggle now becomes the democratic institutions – above all parliaments and the institutions strictly connected with it: general elections and public opinion. These are the main places where modern religious wars are waged. These conflicts are held at bay by, on the one hand, consensus on the observance of the principles of the state of law, and on the other, by the recognition of decisions taken by a majority vote for a temporary compromise which lasts until the next elections or the next vote. The principle of majority serves in democracy as a technical measure, which allows the settlement of disputes which are in essence irresolvable. When there is a lack of common criteria of assessment of the topic in question, only force can ensure universal acceptance of this and not another solution. The principle of majority, and so a quantitative and not qualitative (on merit) criterion, is only the civilised expression of this force.