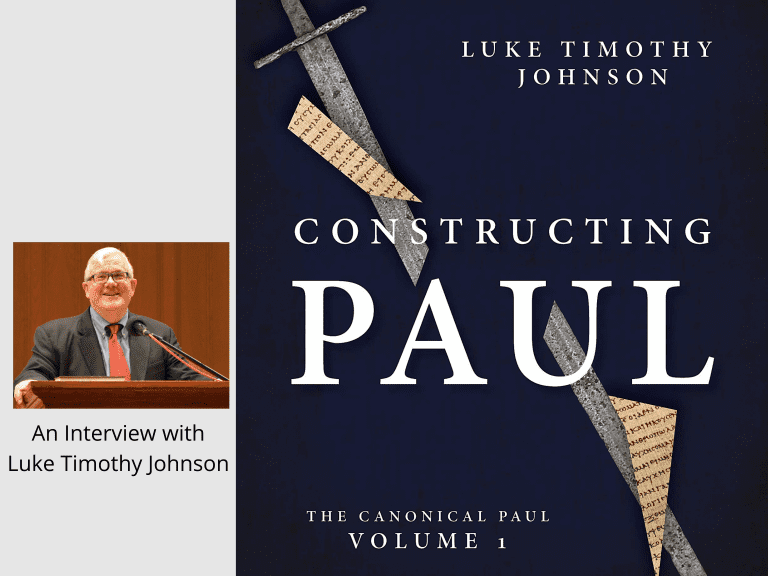

I am pleased to offer to you this interview I conducted with the one and only Luke Timothy Johnson, Robert W. Woodruff Professor Emeritus of New Testament and Christian Origins at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. In this interview (part 1), Johnson talks a little about the story behind his new book Constructing Paul and some of the reasons why he wrote it. More to come also.

NKG: What inspired you to write Constructing Paul?

LTJ: My inspiration for writing the two volumes of Canonical Paul is both personal and professional. First, personal: Insofar as I can call myself a Christian, I have always decidedly been a Pauline Christian. I love all the writings in Scripture (and have written on more than a few!), but for me, Paul’s letters have always spoken most powerfully and provocatively about our life before God when we confess “Jesus is Lord.” His letters are complex and difficult. They demand a lot of the reader, but they also give a lot. They engage me in a very personal way.

Professionally, I seek in these two volumes to provide an alternative to the standard fare. Virtually all treatments of Paul deal only with the “historian’s Paul,” reading only those letters that scholarly dogma has declared “authentic,” and often, an even smaller sample within that selection. In addition, almost all big books on Paul seek to provide a singular “reading” of the apostle based on some principle or theme, and the resulting portrait serves to stand in in the place of the letters themselves.

In contrast, my data base is the “canonical Paul,” that is, the complete collection of 13 letters that the church reads liturgically and doctrinally. My interest is in the apostle of the church. Thus, the basis of my “construction” includes the six letters regularly rejected or ignored by scholars — and consequently also, alas, by many in the church. Working with this larger and more complex collection, furthermore, I eschew any effort to erect a single reading of “Paul’s thought” or “Paul’s theology.” Instead, I seek to provide readers what they need to engage the letters for themselves. The first volume therefore offers a set of essays dealing with everything one needs to know in order to read Paul responsibly. The second volume provides studies of specific issues and themes in all the canonical letters. The goal is to open Paul for others by showing how it can be done through careful attention to the actual text. I don’t provide a “Paul” that can be reduced to a formula. I issue an invitation to engage Paul’s letters.

NKG: You find the common approach to Pauline authorship problematic (Disputed vs. Undisputed Pauline Letters). Why? And what do you propose as a fresh way of approaching this?

LTJ: The conventional approach to Paul — the “historians’ Paul” — distinguishes between authentic letters written by the apostle himself, and inauthentic letters written by a Pauline school after his death. The distinction is based on the false premise that 7 of Paul’s letters are consistent in style and thought, providing a measure against which to test the other six.

In fact, there is no such core. 1 and 2 Corinthians resemble each other but not Galatians and Romans; no reader of Galatians and Romans, in turn, would recognize the same Paul in 1 and 2 Thessalonians. In truth, the canonical collection falls into sets or clusters of letters that resemble each other but are distinct from other sets: the Thessalonian letters; the Corinthian letters, Galatians/Romans; Colossians/Ephesians, and the letters to Paul’s delegates. Only Philippians and Philemon are outliers that help prove the point. In short, the evidence, when assessed neutrally, demolishes the neat distinction supposed by the conventional wisdom and reveals the canonical collection as complex and diverse in a far more dramatic fashion.

Accounting for such diversity and complexity across the board requires a correspondingly more sophisticated theory of literary production. My argument is that the evidence points to a “Pauline school” at work throughout the apostle’s correspondence, so that it is possible to affirm that all the letters were authorized by him during his lifetime and were written under his direction, but that other minds and hands were involved in their actual production.

NKG: In Constructing Paul, you refer to Paul as a “prophetic Jew.” What do you mean by that?

LTJ: Answering the question of “what kind of Jew is Paul” is more complicated than it looks, because of the complexity of his compositions—is he more Jewish when he talks about the Law in Galatians and Ephesians and less Jewish when he does not talk about the law in I Thessalonians?—and the complex forms of Judaism in Paul’s first-century world. He resembles Hellenistic Jews, for example, by using the Greek translation of the Old Testament as Scripture, but he resembles Palestinian Jews like Pharisees and Essenes in his methods of interpreting Scripture, ultimately resembling most that group with which he identifies himself, the Pharisees.

But Paul is by no means just another Pharisee. He is one chosen and sent by God as an apostolos with a commission to proclaim as God’s Word the good news from God concerning God’s presence and power at work among humans here and now through the death and resurrection of Jesus. This mysterion—not only that the Living God works through a crucified and exalted messiah, but that this paradoxical reality means the inclusion of Gentiles in God’s people, and the transformation of all humanity—makes Paul resemble much more the classic prophets like Isaiah and Jeremiah and Ezekiel. He has “seen the Lord,” has been called from his former life “in Judaism” to proclaim to Jews and Gentiles alike that God’s word is to be found, not first of all in written texts from long-ago, but in the experience of himself and others touched by the Spirit of Jesus. His is the demeanor of the prophet. It is not by accident that he applies to himself the language used by Isaiah and Jeremiah for their prophetic call.

NKG: In Constructing Paul, you are critical of postcolonial readings and anti-imperial interpretations of Paul. Why do you find these problematic?

LTJ: The New Testament is a tiny body of literature studied and surveyed by vast numbers of scholars. And since biblical scholarship has taken up a home primarily in the academy (where learned people speak and write to impress other learned people) rather than in the church (where holy people speak and write to transform others), it is peculiarly susceptible to academic chicanery.

Over the course of my career, I have seen wave after wave of theoretical keys promising to unlock the ancient texts: existentialism, psychology (Freudian, Jungian, Adlerian), structuralism (Marxism of some form or another), post-structuralism (whether Derridean or Foucaultian), the anthropology of honor and shame. They have all over-promised and under-delivered, for they have all missed the heart of the literature, which is religious thought about life before God.

If one lives and works in a country that was once a colony of (say) the British, Portuguese, or French empire, and realized that, as Edward Said showed, colonial accounts of indigenous cultures and peoples tended to distort because of western bias (“orientalism”), then, sure, it makes sense to a) critique the distortions brought about by imperial oppression, and b) recover as much as one can of one’s indigenous perspectives.

My problem is with first-world academics using “post-colonialism” as just one more in a series of theoretical perspectives that have, at best, a very limited usefulness in understanding the New Testament. In the case of Paul, in particular, as I have tried to show, all social conditions are adiaphora, and all humans are called to be slaves of God. Paul is not concerned with moving around the furniture of social arrangements. He is much more radical than that. He is concerned with humans being transformed in their very existence so that they can share in the life of God.

NKG: Unlike many other studies on Paul, you advocate for the importance of Paul’s experiences (ch8), especially of the resurrection of Jesus and life in the Spirit. Why do you think other scholars neglect this? Why do you think his experiences are crucial to making sense of Paul?

The real question, I think, is not why I see experience so pervasive a catalyst to Paul’s thought, but why so many other scholars do not see it. As my chapter on the “claims of experience” demonstrates, not only the resurrection experience and the presence of the transforming Spirit that comes from the glorified Jesus are the premises for everything that Paul says (often explicit and always implicit), but equally the ordinary and extraordinary happenings in each church that Paul addresses, are at the heart of his responsive, dialectical, and existential thinking.

Only generations of scholarship conceived as a form of historical/lexical analysis (even among self-designated theologians) can account for an attention given only to Paul’s words, and not to the realities toward which his words point, only to his “ideas” and not to the transforming power which has utterly changed the world in which he and his readers exist. The “new creation” is not a concept; it is a presence and power that shatters and reshapes concepts and demands not new theories but a new form of attentiveness to what God is up to.