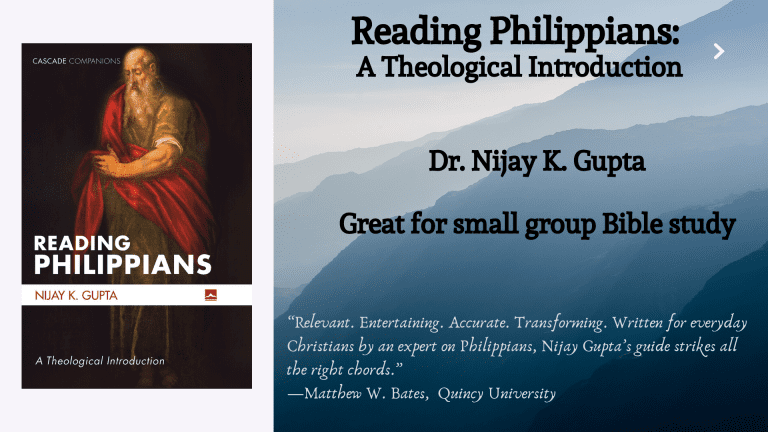

Translating Philippians

This is a blog series reflecting on Bible translation by looking at the Greek text of Philippians. In my book Reading Philippians, I offer my own fresh translation of this letter. I tried to provide a readable, modern English translation, which means I made some untraditional choices. Follow along as I talk through some of these decisions. Here we will look at Phil 3:1-21.

“Beware of the wild dogs” (3:2)

Βλέπετε τοὺς κύνας

Straightforwardly, Paul just says “beware/watch the dogs”—I added “wild” to reflect the fact that dogs in the ancient world were not cute, domesticated pets. They were wild; clearly this was a sharp criticism.

“I hunted members of the church.” (3:6)

διώκων τὴν ἐκκλησίαν

Typically we read about Paul “persecuting.” The verb διώκω, though, was not a religious word per se, but a general term for passionate pursuit (Paul uses it positively in 3:12 and 3:14 about pursing God). The word “hunt” captured that sense of dangerous pursuit.

Our commonwealth and citizen identity belongs to the heavens (3:20a)

ἡμῶν γὰρ τὸ πολίτευμα ἐν οὐρανοῖς ὑπάρχει

This was one of the hardest things to translate in Philippians. Scholars debate about what Paul means by πολίτευμα—citizenship? Community? Commonwealth? I went for a both-and approach, because I think he is referring to socio-political community (commonwealth), and their individual identification with that community. This is all about the fact that our identity and ethos are shaped by our associative social bodies. For the Christian identity to belong to a heavenly commonwealth does not mean we are meant to be disengaged (pie-in-the-sky spirituality). Rather, we “bring” to earth our heavenly (or Kingdom-of-heaven-ly) social values.

“for now we long for and anticipate the coming of our rescuer, the Lord Jesus Christ.” (3:20b)

σωτῆρα ἀπεκδεχόμεθα κύριον Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν,

I made the (perhaps unpopular) choice of not translating σωτῆρ as “Savior.” The word σωτῆρα does, of course, mean “one who saves,” but the Christian vocabulary has spiritualized this word and it has lost its more mundane familiarity. It is not a term that commonly focuses on divine redemption. Imagine you were stuck in a conversation with a boring and talkative person, and a friend comes by and calls you away. You would say, “THANK YOU! You are my σωτῆρ!”

Now, because Paul had just used πολίτευμα, which is a political word, the reader would naturally connect σωτῆρ to a political situation, as where one people were being subjugated or enslaved by another. The “savior” would be the warrior or military leader who rescues them from their oppressor. You might also use “deliverer” or “protector.” I actually like the sound of the word “savior,” if it is clear this not about going to heaven to pluck harps whilst dancing on clouds. It is about being rescued to return to one’s rightful commonwealth, the place where one belongs. This text resonates, then, with, Colossians 1:13: “He delivered us from the power of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of the Son he loves” (NET).