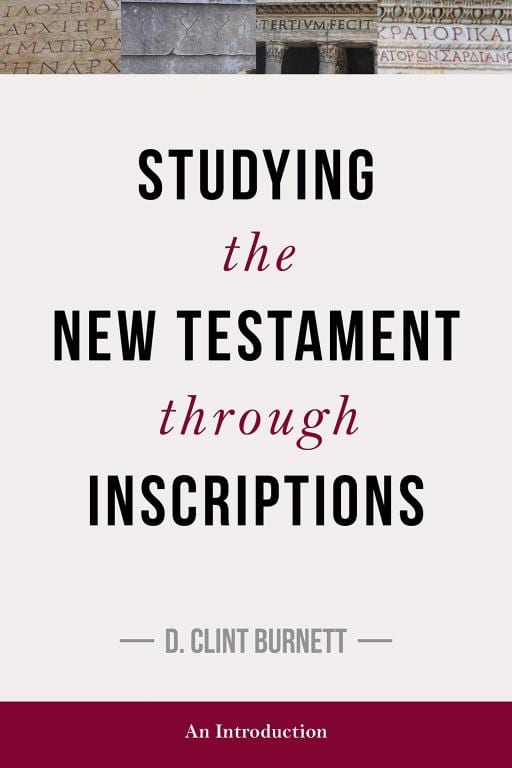

Studying the New Testament through Inscriptions is one of those resources I wish I had 15 years ago. Burnett has done the NT academy a huge service. We need more textbooks like this to aid students and researchers. If you want to do accurate and comprehensive investigation of real life in the ancient world, you need to be able to work competently and responsibly with relevant epigraphical remains; and this book is designed to help you do that.

What are “Inscriptions”?

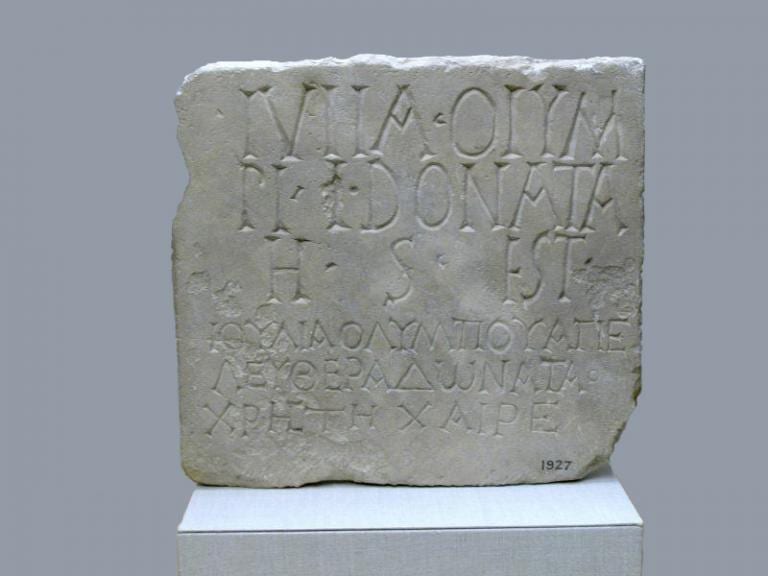

An inscription is “a message written on a durable material” meant to be read by people that pass by (11). All of these kinds of signs can fall under the label “inscription”: civic decree, public honorific praise, dedications (to a patron of a building project, e.g.), sacred laws, graffiti, epitaphs/tombstones, curse tablets. According to Burnett, over 500,000 ancient inscriptions are at our disposal today, yet researchers in NT studies often don’t know where to find them, how to decipher the reference coding, and how to use them for research in a fair and accurate way.

In Burnett’s introduction, he offers a basic guide to the types of Greco-Roman inscriptions (when, where, what, why?) as well as information about where scholars can find databases and collections of inscriptions. Unfortunately, there is not really a “one-stop shop” online or in print for all inscriptions. One has to look in several places such as the set Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum (CIG) and the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL)—and there are more collections with more acronyms (CIS, IGRR, ILS, OGIS, SIG3, TNSI). Burnett also offers a clear chart of the sigla (symbols) scholars use in their transcriptions and translations to give you information about the inscription (pg 56).

After the lengthy introduction (beautifully-illustrated with photos of inscriptions), Burnett showcases the value of epigraphical research for NT scholarship with several case studies. Think of them as a series of academic articles, where attention to epigraphical evidence sheds important light on the issue.

I found each of these case studies carefully researched, often adding crucial pieces to the discussion of topics like Christology, the Lord’s Supper/banquet, imperial loyalty oaths, and women in public.

Strengths

Burnett’s book has many strengths. First off, he really knows his stuff. He has a well-rounded understanding, not only of NT scholarship in general, but the epigraphy world as well. The case studies stand all on their own as excellent specimens of scholarship. As noted above, Burnett includes many, many photographs of inscriptions for illustration, and the visuals really help. In the appendix, Burnett helpfully includes information about printed collections of inscriptions (appendix 1), online databases (appendix 2), and his guide to abbreviations in inscriptions (appendix 3).

Weaknesses

I hesitate to call my comments here “weaknesses”; I enjoyed the book overall, but perhaps better “advice for the second edition.”

I found the introductory chapter (pp. 9-57) quite readable and clear for students (i.e., seminary students). The case studies are quite technical, geared more towards doctoral students or beyond. I would comfortably commend the introduction to my seminary students, but they might be overwhelmed by the case studies. So, I wish Burnett had included maybe a couple of short and simple case studies for the beginner student.

Another desire I had was that Burnett would maybe do a walkthrough of how he would go about using inscriptional information to shed light on an exegetical issue. The case studies are the final product, and they are fine. But I kept wondering—where did he go first? How did he know which databases to use and how many to consult? Did he need to log in? Does it cost money? Is any of this on Logos? Accordance?

There is a handy Greek lexicon that focuses on insight from inscriptions and letters (i.g., Vocabulary of the Greek Testament, aka, Moulton & Milligan, aka M-M). It is my impression that M-M is a great tool for utilizing inscriptional information in word studies. Unfortunately it is an older resource, so does not include knowledge from more recent discoveries. Still, I didn’t really see a discussion of M-M in Burnett. I use M-M a lot, so I wish Burnett had weighed in on its value. The same goes for BrillDAG—I wish Burnett had discussed whether the new BrillDAG includes and handles epigraphical information well.

Finally, I didn’t see Burnett talk about a very handy set of resources called New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity (I think there are ten volumes so far). These volumes summarize insight from several years of discoveries (batched in each volume) and study of inscriptions and letters. For a research project I did a few years ago, I read through almost all 10 volumes and it was a great “cheater’s guide” to inscriptions and what they teach us about the lives of ancient people. For the busy pastor or student, I find NDIEC useful, does Burnett agree?

Final thoughts

Studying the New Testament through Inscriptions is one of those resources I wish I had 15 years ago. Burnett has done the NT academy a huge service. We need more textbooks like this to aid students and researchers. If you want to do accurate and comprehensive investigation of real life in the ancient world, you need to be able to work competently and responsibly with relevant epigraphical remains; and this book is designed to help you do that.