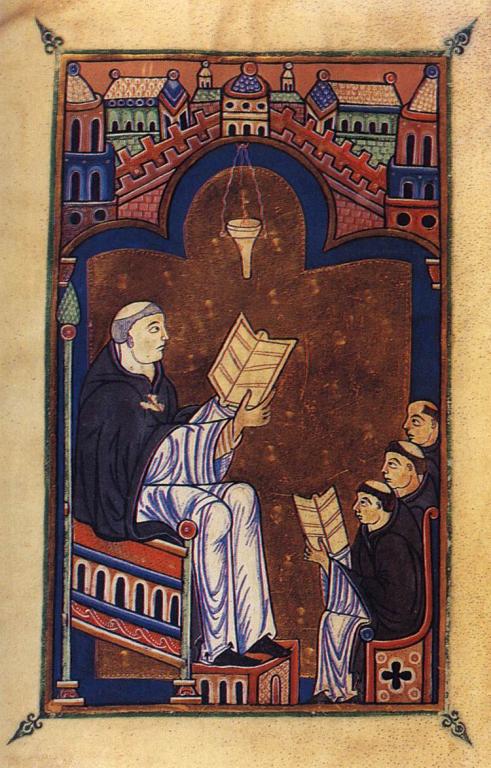

In his twelfth-century guide to reading, The Didascalicon, Hugh of St. Victor identifies three forms of creative work: “opus Dei, opus naturae, opus artificis”—“the work of God, the work of nature, and the work of the artificer.”

Drawing from the opening chapters of Genesis, Hugh distinguishes what God creates (“In the beginning God created …) from what nature creates (“Let the earth bring forth …”) and from what humans, as artificers, create (“They sewed themselves aprons”).

Hugh also speaks of three books of—or ways of reading—creation. One book includes God’s creative work and the work of nature, “which God created out of nothing … in which visible work is written visibly the invisible wisdom of the Creator.” A second is the book of human creation, which humanity “makes out of something.” The third is the book of “Wisdom by which God made all his works,” which includes the life of Christ, scripture, and the sacraments that mediate Christ.

The first book is God’s initial (in)formation of creation. The second book of human “corruptible work” includes human deformation of creation. The third book of Christ, revealed through the incarnation, transforms the human book through new creation.

Hugh’s first two forms of creation—and the first book of creation—have been productively related to theories of information associated with cosmology and biology. Hugh’s third form of creation—and the second and third books of creation—are also helpful as we consider the import and impact of our increasingly complex technological creations.

For Hugh, technology has a central role in reforming our relationship with God and nature. Technology is part of the human quest for wisdom; it extends our abilities and wisdom; and, when used wisely, it can restore what has been corrupted. Further, since wisdom is ultimately grounded in Christ—God’s book of new creation—technology may be understood as part of the transformation of creation that will reconcile divine, natural, and human creativity.

Many acknowledge that, due to our technological advances, human agency has impacted the environment at a scale comparable to natural agency. (This recognition is the justification for the new nomenclature of the Anthropocene.) Indeed, Yuval Harari suggests that human “intelligent design” could replace natural selection as we envelope our natural environment with an informational one.

Moreover, as we continue to reflect on and participate in the information revolution related to autonomous and artificial systems, we are confronting the reality of a new form of agency—artificial artificers with creative powers that must be properly related to other forms of creation.

We know there are dangers associated with unrestrained creation, but we also know that our creative impulse resists restraints and that appropriate restraints are constantly shifting. As we create robust narratives and ethical frameworks for navigating our new informational and technological reality, Hugh’s forms and books of creation can help us imagine not only a way forward but also the future being revealed to us.