The rediscovery of my Chineseness after my conversion to Eastern Catholicism, which seems to be a recurrent theme on this blog, has prompted a number of mystagogical reflections that I hope to write through in this third year of blogging. Here, I pick up on where I left off with the death of the novelist Louis Cha.

When I was eight, my maternal grandpa, whose Shanghainese background meant that we called him ‘good grandpa’ 好公 (Cantonese hou2 gung1), told me the craziest story. He knew that I was learning about Journey to the West 西遊記 in Chinese school, and he decided to relate to me a tale that I would never have learned there. Chinese school took place at church, and it so happened that at the time I was going to two of them, a Mandarin-speaking one on Fridays at my childhood church and a Cantonese-speaking one on Sunday afternoons at a church where my dad was the pastoral intern. The Chinese school textbooks had decided that it was time that we were introduced to what I call the four-by-four proverbs, the idioms expressed in four Chinese characters, like draw serpent add legs (being so extra, usually to one’s own disadvantage), the frog at the bottom of the well (someone who is narrow-minded because they think their experience is all there is to the world), down well drop rock (kicking someone when they’re down), and spear against the shield (being self-contradictory, like trying to pierce one’s own shield with one’s own spear).

Chinese Protestant churches, whether Cantonese or Mandarin, are usually places of repressed sexual desire, which doesn’t mean that sex is not talked about, but rather that kids learning about sex in them discover it in the shadows. It is no surprise, for example, that it was not in school that our cohort of boys discovered the desirability of the naked female body, but in bursts of excitement in the church fellowship hall after a few of them had seen Titanic in theatres. Try as the uncles and aunties might have retroactively to be progressive and address the questions of sex especially when a sex scandal tore through our congregation in the mid-1990s (and we were by no means the only Chinese church in the Bay Area to have one), the path of awakening usually took place as we boys approaching puberty were taken in non-church private settings to see films that, as Slavoj Žižek puts so well in The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema, did ‘not teach us what to desire, but how to desire.’ The space of the church became the informal site of discussion about such lusts, quite apart from any programming. I still remember the summer retreat when, after I had gone to bed only to be awakened by fire ants surrounding me, I learned that my friends were outside playing strip poker. The ringleader of the bunch, of course, is now a staff worker at an evangelical organization.

That was all a ways off timewise from my initial encounter with Journey to the West in Chinese school, but suffice it to say that it was not in Chinese school that I learned about the story of the Monkey King, Sun Wukong, getting on his big stick, flying to the ends of the world, and pissing on a pillar holding up the world, only to find out upon his return that he had remained the entire time within the palm of Śākyamuni Buddha. That was from my dad, who told me the story as a joke when he learned that I was learning about Journey to the West in church. He was shocked to find out that it hadn’t been relayed in class. If that was too dirty for the kids, then what about Journey to the West, which is basically a giant pissing contest, was clean enough to teach?

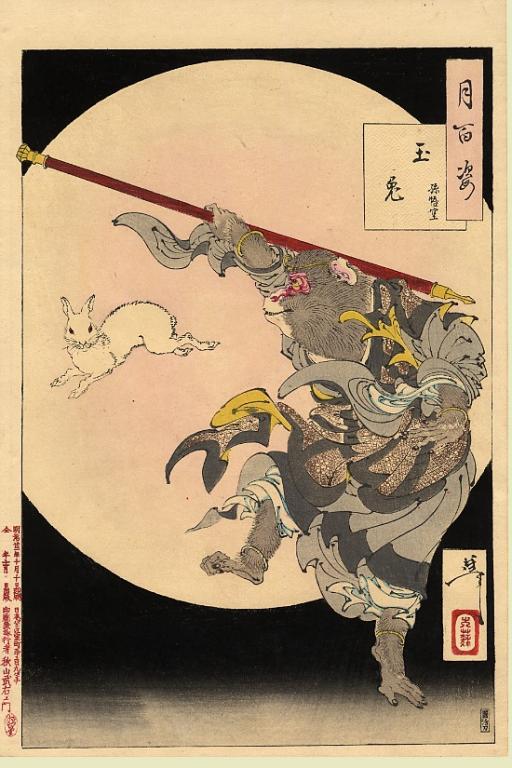

My good grandpa one-upped my dad. He decided to tell me a story from the end of the Journey to the West, the one about the Jade Maiden Rabbit. The basic plot of the novel is that the monk Tang Sanzong has gathered a few companions, like the Monkey King, Pig Eight Precepts, Friar Sand, and Yulong the Horse on a quest to recover the Buddhist Scriptures from Vulture Peak in India, and on their journey, they do battle with spirits and ghosts, heroes and gods, that attempt to obstruct their way, sometimes even sent by the Buddhas. The story of Jade Maiden Rabbit occurs when they are in India. Posing as a princess, Jade Maiden Rabbit concocts a plot to marry the monk and suck out all of his yang force. The Monkey discovers the plot and engages in an epic battle with her to reveal her true form, and as he has the upper hand, suddenly both the bodhisattva Guan Yin and the moon goddess Chang’e appear and rescue the Jade Maiden Rabbit, revealing that she is actually the rabbit figure on the moon who grinds the life potion for the moon goddess to ingest so as to live forever in her lunar space. As this is going on, Pig begins to flirt with Chang’e, referencing the time that he had tried to initiate an affair with her years ago and got demoted from his place in heaven to earth.

My good grandpa was having such a good time telling this story, while I was bored, at least up to the point when he began talking about Chang’e the Moon Goddess. My little sister had just recently given a public speech in Chinese school about the story of Chang’e, about how she was a beautiful woman who drank the elixir of life and floated up to the moon where she lived forever. For me as an eight-year-old, the sexual undertones of the Jade Maiden Rabbit story – besides Pig flirting with Chang’e, by what mechanism, one wonders, was Rabbit going to suck out the yang force from the monk she was plotting to marry? – went right over my head. I wanted to learn more about Chang’e, how she got off that moon, and frustrated, my grandfather and I got into a shouting match that was overheard by my mom, who was shocked that he was telling me such an ‘advanced’ story.

Mom, of course, was a sucker for these stories too. She was a Chinese literature major in university, and before that, she had binged her way through Jin Yong’s wuxia novels as an eleven year old until her Methodist headmistress godmother had confiscated them from her. It was around that year that TVB Jade, the Hong Kong broadcasting company that aired its programs internationally wherever Chinese people lived (like where we were in the Bay Area, where we watched KTSF Channel 26), began broadcasting The Legend of the Condor Heroes. Mom was nervous about that, I remember, because she didn’t want my sister and me addicted to them, passing on the practice of binging to the next generation, as it were. But as much as Mom claimed to have repressed her appreciation for these stories of martial heroism, she couldn’t help but binging, which meant that I joined her on the journeys of Guo Jing and Huang Rong and their encounters with other heroes and villains, like Hong Seven Grandpa, Old Childish Zhou Botong, West Poison Ouyang Feng, and Eastern Heretic Huang Yaoshi.

But the next year, which would have been after good grandpa told me the story of Jade Maiden Rabbit, Mom got nervous again. The sequel to the Condor Heroes was coming on, and as she remembered, there was a lot more sex to be explored in the taboo relationship between the child Yang Guo and his martial master and subsequent lover, the Little Dragon Maiden. She didn’t know what to do when the plot got to the part where the Little Dragon Maiden wants to step things up in Yang Guo’s education in the Ancient Tomb Sect’s Jade Heart Sutra form and practice the passing of inner strength between two bodies. The form requires them to both be completely naked, and in terms of the plot, their actions lead to their discovery by a lustful Taoist practitioner and the Little Dragon Maiden getting raped by him, though she thinks she has slept with Yang Guo and doesn’t learn till much later that she has been violated. It was also the first time I had seen such acts depicted on television, and I remember Mom being stressed while watching it with us. My sense is that she later refused to let us watch Grease because she didn’t want to go through the stress again.

As I reflect on these earlier events in my life in a time that is admittedly even far later than the more crucial moments of childhood sexuality that Sigmund and Anna Freud prescribe for analysis, I become increasingly thankful for the Asian American literary master Frank Chin‘s critique of the place of Christianity in Asian America. It has taken me quite a long time to understand the various strands of Chin’s anti-Christianity, especially being a Christian myself, and I still maintain that for the most part, he goes a bit off the edge in his diatribes about the incompatibility of Christian praxis and Chinese martial and literary arts. And yet, he is not completely wrong, especially in terms of the Chinese Christianity with which I grew up, which is as indebted to its inculturations in Republican China, British Hong Kong, and Kuomintang Taiwan as it is to its Anglo-American missionary forebears. It is frequently in vogue to complain about Confucian hierarchy in such communities, that Chinese culture becomes oppressive to Christian practice because of its emphasis on strict hierarchical relations in the family. But that is not Chin’s critique. Instead, Chin is highlighting the contradictions between the face of asexual purity presented by Christianized Chinese Americans and the sexual freedom explored even in the Chinese classics. Asexuality and sexual freedom do not mix. When they do, they form a contradiction in the psyche. It is, as we Chinese say, holding one’s spear against the shield, attempting to pierce the defense with one’s own weapon (which is a sexual metaphor if I ever saw one).

When Sam Rocha told me that he’d give me three years to narrate myself on this blog, he also said that becoming Catholic would form me in such a way that I’d lose my asexuality. I did not know what he meant by that, and I think neither did he, as he chalked it up to the trope of the asexual Asian combined with the ideologies of Protestantism. But as I have been exploring it, that combination perhaps has been lethal because it is the sexual paralysis that comes of being steeped in the playful and openly sexual stories of Chinese literary culture and folk phenomenology and then having to present a face of being sexually ignorant with sage-like seriousness to a world that expects Chineseness to be equated with the model minority. Through the spiritual direction of the last year, I have been exploring what it means to understand the eros of the Christian life as I work it out in our Kyivan mystagogy, and as it turns out, reclaiming who I am as a sexual being has brought me back to these stories and the contradictions they wrought in my approach to puberty.

The funniest thing is that as I work out my salvation as such in fear and trembling – which you can take as a double entendre, if you wish – I do so in the midst of a people in communion with others and wishing for the re-establishment of common life with still other churches that is as colonized as the one of my past. Plenty of Catholics and Orthodox are as afraid of sex as my Protestant forebears, especially the Protestant converts. But what I find in this church is that we have a theology for the eros I am rediscovering, and it is to be found in the icon, which we take as not so much an image at which we gaze but that gazes at us with the light of Christ as windows from heaven. Such an iconographic view of the world evokes our desire to be found in the other and to be wrapped up in their energies as they are consumed by ours. This sensibility, I am willing to argue, lies at the heart of Catholic spirituality, and I suppose one avenue of what I will be doing as I continue to write my reflections is to muse on how this has led to a re-integration with my Chineseness in a way that such an anti-Christian as Frank Chin would have to admit is the work of the One-Who-Is.