David Russell Mosley

26 August 2013

Beeston, Nottinghamshire

Dear Friends and Family,

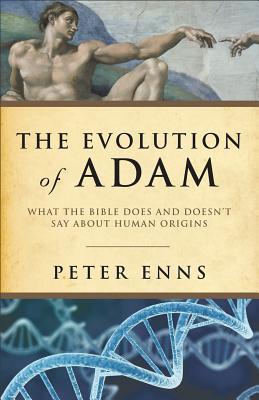

Here is my review of Peter Enns’ The Evolution of Adam. I hope you enjoy.

Peter Enns seeks to evidence that in the Christian tradition, we do not need a historical Adam and Eve, that is, that our theology will not rise or fall on Adam and Eve’s existence or lack thereof. Enns first begins by discussing the changes geology and evolution caused in modern thinking about the age and construction of the world. He then goes on to note how biblical scholars began in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to notice that books such as Genesis seemed to be compilations of various sources. Enns then shifts to discuss how early Israel seems to have understood and used Genesis and how Paul used the OT scriptures in general and Adam in specific. Essentially, Enns suggests that while Adam is treated as historical for Paul, more significantly, Adam is a theological example of the plights of humanity, sin and death. Enns does not suggest that we replace theology/Scripture with evolution, but that we must recognise that the two speak different languages and must be synthesised.

While I generally agree with many of Enns conclusions about Genesis and evolution, I have several issues with this book. His almost naive acceptance of modern biblical, historical-critical method of interpretation aside, Enns spends no time on two issues that seem rather important from his conclusions. First, Enns suggests that all we really need to know is that sin and death are problems for humans and we need ask no further. Enns completely ignores the question of evil and his approach would almost suggest that God created humanity as sinful, or that sinfulness naturally arises in humanity, which comes to the same thing. The second issue Enns ignores is how the tradition understood/understands Genesis and Adam and Eve. For that matter, chronologically speaking, Enns ignores what the Gospel writers have to say on the issue. One could perhaps forgive Enns for ignoring the early and medieval theologians as outside his purview since the subtitle says ‘What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say about Human Origins’. Although Enns does make fleeting reference to the reformers. However, one cannot forgive Enns for promising in the title to tell us what the Bible does and does not say about this topic and then focus only on the Old Testament Scriptures and Paul. Admittedly, Adam only appears in two other places and seems to have less theological import than in Paul, but to ignore them entirely seems negligible.

In the end, I would recommend this book for those interested in learning more about this topic, but more so would I recommend reading Conor Cunningham’s Darwin’s Pious Idea and Peter Bouteneff’s Beginnings.

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley