David Russell Mosley

Ordinary Time

St Teresa of Avila

15 October 2014

On the Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

I sometimes wonder about the way we (and by we I mean those who tend to align themselves with evangelical churches, but I’m sure it’s more widespread than this) use the word legalism. It feels as though we use this word as a shield to guard against asceticism openly and sometimes discipline secretly. As anyone who has spent any time reading these letters will know, I believe in liturgy, I believe in Christian practices beyond, but not excluding, things like feeding the hungry, evangelising, going to church, etc. I’ve even experienced some Christians who wouldn’t want to make hard and fast rules about any of those things either. How many times have I heard sermons or small group lessons––how many times have I said––don’t let these things become tasks on a to-do list, doing them just to check them off? And yet, this isn’t exactly the picture given to us by the Scriptures, and it certainly is not the task given to us by those who have come since the writing of the Scriptures.

Let me give you a few examples. First, from Christ himself: In Matthew 23, Jesus is upbraiding the pharisees. In the Gospels, these guys are the villains in every story where they appear. This makes it hard for us to remember that they weren’t always the bad guys. For a long time they were the religious faithful when even the priestly classes were failing. Christ recognises this when he tells his audience, ‘The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, so practise and observe whatever they tell you—but not what they do. For they preach, but do not practise’ (Mt 23.2-3). While the pharisees in Christ’s day are falling short in acting rightly, they are still to be obeyed. In fact, Christ notes later on that the Pharisees do right in tithing even on the smallest of herbs they have, but do wrong in neglecting the weightier aspects of a righteous life (Mt 23.23). So it would seem that some regular disciplinary practice, such as the pharisees did and taught others to do, were not inherently wrong, only their attitude was.

My next example comes from the book of Acts. The story comes from Acts 3. It is a familiar one. Peter and John come across a lame beggar asking for money. Peter tells him they have no money, but what they do have, they will give to him. Then he commands the lame man to stand up in the name of Christ and he does. It is an awesome story about the power of Christ the healer and defending the faith in the face of adversity (for Peter and John are later taken to the Sanhedrin and commanded not to talk about Christ). However, there is an important element at the beginning of the story which I left out. Peter and John weren’t simply out on a stroll. Rather they were headed to the temple for an appointed time of prayer, ‘One day Peter and John were going up to the temple at the time of prayer—at three in the afternoon’ (Acts 3.1). It seems that the apostles were in the custom of praying at set times during the day.

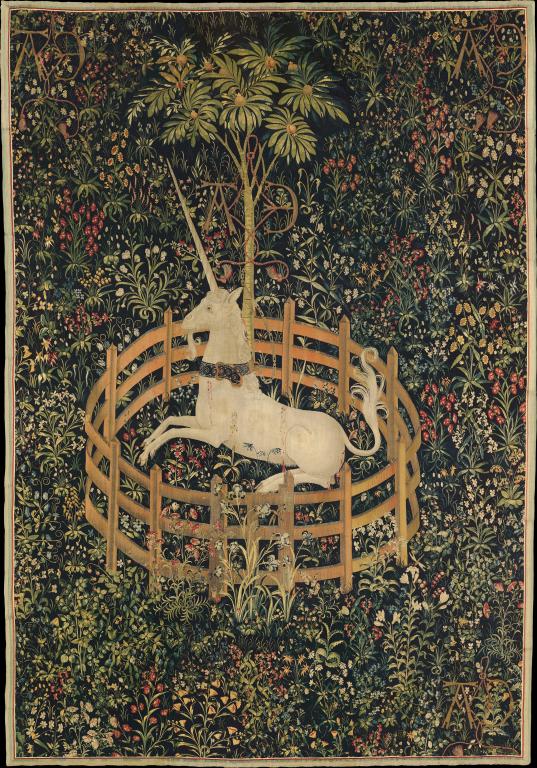

We have gotten ourselves into the habit of thinking anything we do or learn by rote cannot be felt, cannot be a lived reality. Yet I think the shield of legalism is really a prison keeping us from a deeper reality, one of order and spontaneity. In a previous letter, I wrote how physical things and spaces matter. Well, so do our actions and there are some things the Church has been for such a long time (having a liturgy, daily fixed hour prayers, fasting in certain seasons or on certain days, etc.) that today we might call legalism. Yet, if we allow them, these things can transform us. Oh it is true that simple actions and actions only will not necessarily make a difference. Two students of the piano practice their scales and arpeggios everyday. They learn their theory, perform their songs, etc. One does so dutifully, the other sulkily. Yet the one who does so dutifully will be the better pianist over all. They will feel the music, but only in part because of their attitude, their actions have much more to do with it. In fact, even the sulky one can be made to come round, simply by doing. Remember the parable of the two sons. One promised to work in the vineyard but didn’t. The other swore he wouldn’t but did. C. S. Lewis talks about this in Mere Christianity. What Lewis says about pretending to be Christ, can, in my opinion, be applied to all ritualistic, disciplined, ascetic, practices:

‘What is the good of pretending to be what you are not? Well, even on the human level, you know, there are two kinds of pretending. There is a bad kind, where the pretense is there instead of the real thing; as when a man pretends he is going to help you instead of really helping you. But there is also a good kind, where the pretence leads up to the real thing. When you are not feeling particularly friendly but know you ought to be, the best thing you can do, very often, is to put on a friendly manner and behave as if you were a nicer person than you actually are. And in a few minutes, as we all have noticed, you will be really feeling friendlier than you were. Very often the only way to get a quality in reality is to start behaving as if you had it already’ (Book 4, Chapter 7).

When we fast, pray, do church in a liturgical manner, follow the Church Calendar, etc., we are practising for life with God. We are, in a sense, pretending that Heaven has come to Earth, and as we pretend, we begin to make what we pretend into reality but only if two conditions are met: 1. We do so by, with, and in the grace of God; 2. We do so not simply to look better ourselves, but to make the world look better.

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley