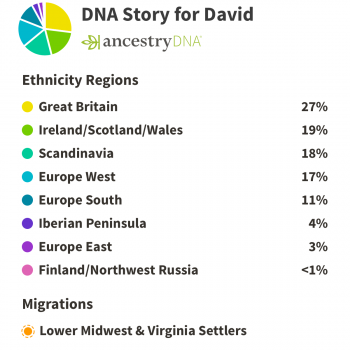

David Russell Mosley

Description

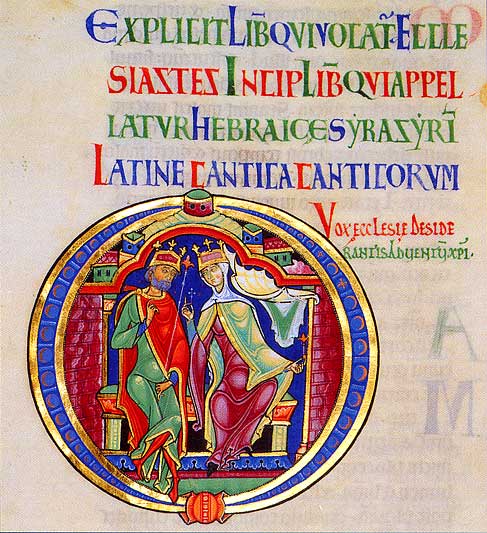

Cymraeg: Priflythyren o Ganiad Solomon yn eglwys gadeirol Caerwynt.

English: Capital from the Song of Solomon in Winchester Cathedral.

Date 1100s

Source http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~jtreat/song/270.html

Author Unknown

(Public Domain)

Ordinary Time

12 September 2016

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

The other day I came across this “provocatively” titled article, “Vagina, Penis, and Being Created as Sexual Beings,” by Daniel D. Lee. If the title wasn’t enough to draw me in, the first line certainly did it: “’Daddy, I have a vagina and you have a penis, because I’m a girl and you are a boy.'” The rest of the article goes on to note how this little girl’s father (the author of the piece) initially reacted to his little girl using the correct terminology for reproductive organs, and how we need to affirm our bodies, particularly as regards sex.

This really ought to be a great piece. We are created as sexual (and sexually differentiated) beings. Sex and sexuality are not things of which we should be “puritanically” ashamed. And yet, Lee make several, if not wrong, then misguided (in my opinion) moves. For instance, Lee notes that many early heresies (particularly those of Gnostic variety) “had difficulties with the idea of a good physical creation and a good body.” Which is more or less true (though it’s also true that believing matter was created by an evil God led some groups to rather Epicurean and Hedonistic heights). Lee goes on, however, to suggest that this introduction of Greek ascetic philosophy not only infiltrated the heretics but the orthodox as well. Lee writes, “the early church considered sex an inconvenience at best and a terrible source of evil at worst.” Of course the fact that sex can be a terrible source of evil (rape comes to mind, as does pornography, or treating the other as merely an object for your sexual gratification) is glossed over in an effort to remind us that sex is good. It is true that many of the Church Fathers had some difficulties with sex (Augustine particularly comes to mind). And yes, you do also have Gregory of Nyssa and Maximus the Confessor who believed the sexual differentiation in general was given to us because God knew that we would fall and need it to procreate. That none of this stopped people from having sex (and thus procreating) seems forgotten or ignored in order to push the narrative Lee has.

One can see, even if one looks none too closely, Adolf von Harnack at the back of much of this. The supposedly anti-sex early church (as indicated by lifting the virgin above the married, and I mean who would do that, it’s not as if the Apostle Paul says anything of the kind….) is so because the influences of Greek “asceticism” pushed out the Jewish Gospel. Lee goes so far as to write:

“If the church didn’t become anti-Semitic, losing its roots in Judaism to Greek ascetic influences, the story might have been different for our sexual bodies as we remember that we are grafted to Israel through faith in Christ and that we worship a Jewish Messiah.”

This, of course, is ridiculous. Yes the Church has has a strained relationship with actual Jewish people and in that sense has certainly been anti-Semitic. However, this is not the same as suggesting that Church rejected totally its Jewish/Hebrew origins. Especially looking at the early and Medieval Church do I find this claim difficult to sustain given the prominence of the Old Testament and the Apocrypha. Ah, but here Lee has a smoking gun: the Song of Solomon:

“The Bible has a whole book on celebrating sex, Song of Solomon, although many would rather see this book allegorically to cover up their own discomfort.”

Ignoring for a moment that Lee does not note that allegory forms one part of a fourfold method of reading Scripture, the first method of which is the literal reading, Lee does not seem to understand the “point” of reading Song of Solomon allegorically. You see, the only reason reading Song of Songs as allegory works (whether one reads it as God’s love of humanity or Christ’s love for the Church) is precisely because we recognize the erotic love that exists between lovers, who have sex. I am sure there are many who attempt to read Song of Songs as “purely” allegorical, that is completely divorced from any understanding of the erotic love between a man and woman, but that is an inherently impoverished and ultimately impossible reading. The text literally makes no sense if we can’t first understand its literal meaning.

Lee also makes brief mention of sexual restrictions in medieval Europe and while I don’t have resources to hand to help contextualize this let me say at least this: there was still plenty of sex being had no matter what kinds of laws were in place or what they actually meant.

Lee’s ultimate point is a good one. We need to affirm the fact that we are, as a species, sexual and repression of that fact is not good. But Lee makes many missteps along the way. He seems to eschew celibacy altogether. Or at the very least, since he claims that the early church made the sexual into second-class citizens, it is difficult to see how the celibate are not made into such by Lee’s positions. (For an excellent essay on monasticism and sexual orientation see fellow Patheos Catholic blogger, Artur Sebastian Rosman’s post here). In the end, while I agree with Lee that we need to see the fact that we are sexual beings as good, I disagree with how he diagnoses our current problems. Lee even admits that the proliferation of sex in the modern imagination has not solved our problems (nor has he actually made the case that there was a problem before, although I think he’s right that there was, just not about how he understands it). So, we are sexual beings and this is good, but we cannot and should not simply blame our patristic and medieval ancestors in the faith, nor the Greeks, for this. Let’s actually do the work, read the texts, and understand the sources. That, or, we must simply diagnose that we have a problem now and seek to fix it.

Sincerely,

David