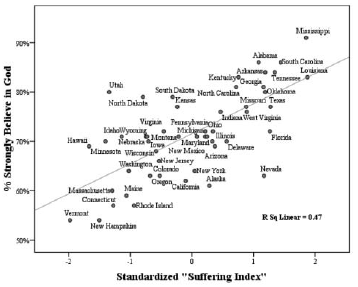

Here’s a Friday evening paradox for you. For most atheists, the abundance of suffering in the world is a pretty clinching argument against the existence of a moral god. Yet religion seems to thrive in places where suffering is greatest (the graphic shows the correlation across US states between a basket of ‘suffering’ measures and belief in God).

Here’s a Friday evening paradox for you. For most atheists, the abundance of suffering in the world is a pretty clinching argument against the existence of a moral god. Yet religion seems to thrive in places where suffering is greatest (the graphic shows the correlation across US states between a basket of ‘suffering’ measures and belief in God).

What gives? Kurt Gray, a psychologist at Harvard, has some novel ideas about why this should be.

First off, he points out that we have a tendency to find intelligent agents to explain events – we’ve got a ‘hyperactive agent detection device’. What’s more, he suggests, that’s particularly important for things that have gone wrong or caused harm. You can understand this in evolutionary terms, because intelligent agents are the biggest threats to survival.

Now, it’s true that people also attribute good events to the action of their God. But Gray points out that negative experiences are more powerful, and people are more likely to attribute them to an intentional agent.

In one rather nice study, he gave some ‘disaster’ scenarios to a group of believers and asked them whether God (they were all Christians, presumably) or a human was to blame.

The scenario was this. A family was picnicking in a valley, when suddenly there was a flood.

- The flood was caused by an evil dam worker, but the family escaped with no more than a ruined lunch (human cause, no harm).

- The flood was caused by an evil dam worker, and the family were all killed (human cause, harm).

- The cause of the flood was unknown, but the family escaped with no more than a ruined lunch (unknown cause, no harm).

- The cause of the flood was unknown, and the family were all killed (human cause, harm).

So, for which of these scenarios was God to blame?

Unsurprisingly, God was not held responsible for the first two scenarios. More surprisingly, God wasn’t responsible for the third one, in which the family managed to escape.

The only scenario where God was blamed was the last one, where the family were all killed for an unknown reason.

Now this is fascinating stuff, but it doesn’t really clinch it for me. Where is the equivalent study, but where there was a positive outcome? Perhaps God would be held equally responsible for that.

Nevertheless, this does show that people only invoke God to give meaning to events if those events have a moral dimension. It’s not that they can’t understand acausality, it’s that they’re driven to find an intelligent actor behind harmful events.

Gray’s theory gets a bit more complicated from here on. Moral acts require two people – someone to do the act (the agent), and someone to receive it (the patient). This way of thinking is so ingrained that we tend to typecast individuals as either moral agents or moral patients.

Mother Theresa, for example, is typecast as someone who can do good things but is relatively insensitive to pain or pleasure. When people have to choose someone to receive unavoidable pain, they choose Theresa – presumably because they think her to be less sensitive.

Now this is fascinating because people tend to think of God as an agent that can do moral actions, but can’t experience them. In other words, God can do good and bad things, but good and bad things can’t happen to God.

Bringing all this together, what seems to be happening is that when some piece of bad luck happens, people automatically view it in moral terms. They typecast themselves as moral patients – and that, of course, then means that there must somewhere be a moral agent.

God, according to this theory, is the ultimate moral agent.

Gray concludes that religion, far from being a cause of morality, is actually a consequence of it. Because of the way our minds analyse moral situations, morality actually causes us to invent a god. He says:

God may be more accurately characterized as “God of the Moral Gaps,” a supernatural mind introduced into our perception of the world because of the underlying dyadic structure of morality. Seen in this light, God stems not only from agent detection but from patient detection as well, both of which arise from a persistent need to maintain the moral order of a universe consisting of moral agents and patients. Such a view of God can explain why He thrives on human suffering and why His mind is perceived as curiously one sided.

__________________________________________________________________________![]()

Gray K, & Wegner DM (2009). Blaming God for Our Pain: Human Suffering and the Divine Mind. Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc PMID: 19926831

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.