Do you ever get the feeling that one reason a lot of people can’t stomach the theory of natural selection is that they hate the idea that everything we see around us is the result of blind chance. Hostility to the notion of chance is certainly a recurrent theme in creationist objections.

Of course, evolution by natural selection is not really evolution by chance, as the creationists claim. But even so chance does play a role. Stephen Gould, in many of his essays, repeatedly drove home the importance of chance (or rather, contingency) in evolution. As he argued in the essay “Eight little piggies“, there doesn’t seem to be any particular reason that we have five fingers, rather than 6, or 7, or 8. That’s just the cards we drew.

But there is another perspective, championed recently by Simon Conway Morris in his book Life’s Solution. He emphasises rather more the many occasions of convergent evolution, and makes the controversial case that the development of sentient life was more-or-less inevitable – in flat contradiction to Stephen Gould.

I say all this by way of introduction to a rather intriguing study by Bastiaan Rutjens, at the University of Amsterdam. Along with his colleagues, he’s been looking at how threatening people’s sense of personal control can change their attitudes.

He takes his inspiration from Aaron Kay, at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, who has shown that making people feel like they are not in control causes them to activate beliefs that restore their sense that something, at least, is in control – like a belief in a controlling God, or support for a strong government. It’s a theory called compensatory control.

What Rutjens did was to prime students (140 in total) by asking half of them to write about a bad experience when they did not feel in control, and also to give three reasons why the future is not controllable. The other half did a similar task, but emphasising and reinforcing their sense of control.

Next, they were given three short descriptions of various theories of evolution, and asked which one they thought more likely to be true. The three theories were Intelligent Design (ID), the Theory of Evolution but emphasising its randomness (TE), and the “Conway Morris” Theory of Evolution (CMTE).

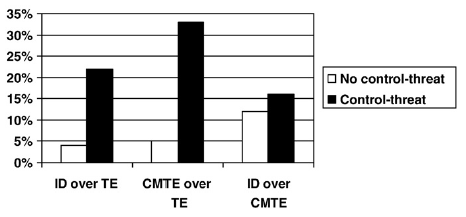

The graph shows what they found. Now, remember this is The Netherlands, so most of the students were pretty godless. Without the ‘loss of control’ priming, almost none of them approve of ID – or, for that matter, CMTE.

But when primed to feel loss of control, the students were much more likely to prefer either ID or CMTE (although still a large majority accepted evolution).

So the students seem to compensate for their feeling of anxiety and uncertainty induced by their loss of control by turning to theories about life that reassure them that there is some kind of plan in place.

All this may help explain why evolution is unpopular in parts of the world where life is full of uncertainty. And it might help explain why religion and rejection of evolution so often go hand in hand. Both are tools that provide compensatory control.

But what’s really interesting is that ID and CMTE seem to be interchangeable. I wonder if presenting Darwinian evolution in CMTE terms might help to get religious people on board. After all, Conway Morris is himself a Christian, which has perhaps influenced his views on evolution!

![]() Rutjens, B., van der Pligt, J., & van Harreveld, F. (2010). Deus or Darwin: Randomness and belief in theories about the origin of life Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46 (6), 1078-1080 DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.009

Rutjens, B., van der Pligt, J., & van Harreveld, F. (2010). Deus or Darwin: Randomness and belief in theories about the origin of life Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46 (6), 1078-1080 DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.009

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.