Look around the world, and you’ll find that most gods and magical entities are surprisingly similar to regular people, but with one or two magical powers. The same goes for most works of fiction – your typical superhero is, in most respects, a pretty regular guy.

At first sight, the Judaeo-Christian god seems to be an exception to this rule. But if you look at how Christians often relate to their god, never mind how it is portrayed in the Bible, it’s not really such an anomaly.

Back in 2002, Pascal Boyer proposed that this was not an accident. He suggested that mundane, everyday objects are instantly forgettable, and that really weird stuff is just to hard to remember. What really stands out, and what our brains intuitively latch onto, are things that deviate only a bit from the normal. He called these ‘minimally counterintuitive ideas’ (MCI).

Over the past 10 years, research into this idea has produced some support, but also some experimental results that didn’t fit the predictions.

The most recent experiment has taken advantage of the virtual reality world of Second Life. By using a virtual environment, they able not only to create a set-up that would be impossible in the real world, but to study people from different cultures and people who don’t typically participate as subjects (i.e. people other than students).

The experimenters, Ryan Hornbeck at the University of Oxford, UK, and Justin Barrett (now at the Fuller Theological Seminary in California) created a kind of virtual museum containing 18 objects. Half of these were everyday (such as a ball hitting a wall) and half had something weird about them (such as a parrot that disappears).

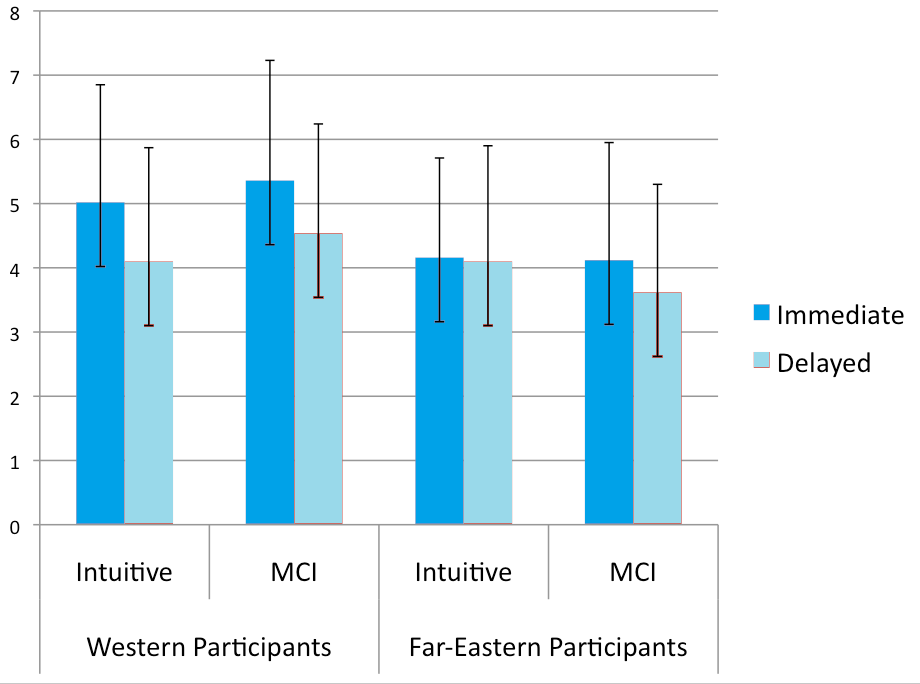

They lead their study subjects (50 native-English speakers living in the West and 50 native-Chinese speakers living in Asia) round this museum, and let them briefly view each object. Afterwards they tested them on how many they could remember. After a while (up to 15 days later) they were invited to be tested again.

As shown in the graphic, the Westerners were more likely to remember the ‘minimally counterintuitive’ objects than the intuitive objects – whether tested immediately or after a period of days. For the Chinese speakers, there was no difference in immediate recall, but there was a difference in the delayed recall.

They found that the longer the period until the second test, the more likely it was that the intuitive items would be forgotten. That’s what you would expect – but that’s not what they found for the MCI objects. For these, memorisation seemed to be constant, whatever the delay.

That suggests that MCIs that actually get remembered are less likely to be forgotten, compared with intuitive memories.

Intriguingly, they also found that age had an effect.The older participants were equally good at remembering MCI and intuitive objects. Younger participants, however, were significantly better at remembering the MCI objects.

The researchers were intrigued by why that might be. What they end up suggesting is that, for young adults who are still learning about the world, it pays off to devote a lot of mental energy to memorising and assessing things that deviate from the expected.

By later adulthood, however, “the most important exceptions are likely to have already been encountered”. As a result, anything that turns up that looks weird and out of place to an older person is likely just to be a one-off aberration, and so not worth paying too much attention too.

A sobering thought!

![]()

Hornbeck, R., & Barrett, J. (2013). Refining and Testing “Counterintuitiveness” in Virtual Reality: Cross-Cultural Evidence for Recall of Counterintuitive Representations International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 23 (1), 15-28 DOI: 10.1080/10508619.2013.735192

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.