Regular readers of this blog will be familiar with minimally counterintuitive ideas. That’s the theory that, for a fictional character or object to be memorable, it needs to have remarkable characteristics that make it stand out – but not too many, or it becomes impossible to remember.

In other words, the supposition is that we’re geared up to look out for and remember things that seem normal but which break the rules in some important way.

Now, although this effect has bee shown in adults, it’s less clear whether children’s minds work the same way.

Konika Banerjee, a psychologist formerly at Harvard (but now at Yale), along with colleagues ran a series of experiments in which they sought to find out just how counterintuitive a concept should be to make it really memorable to children.

They took groups of children aged seven to nine years and read them a story about a child walking around its neighbourhood and encountering a series of objects, some of which had normal characteristics and some of which had counterintuitive characteristics.

They varied the number of countintuitive characteristics per object from one in the first study up to three in the third study. Then they asked the kids which objects they could remember, and what they could remember about them. They did this straight after the study and also a week later.

These were an exceptionally well designed experiments. They made multiple version of the stories, in which they mixed around the objects so they could be sure that it wasn’t the objects themselves that were affecting recall. So, for instance, one version of the story ran like this:

In the bedroom, they saw a rake lying on the carpet. The rake had a wooden handle and could breathe well underwater. After leaving the bedroom, the kids continued on into the basement, where they noticed a hammer on top of a table. The hammer felt heavy to hold and was brown in color.

While the second version ran like this:

In the bedroom, they saw a hammer lying on the carpet. The hammer had a wooden handle and could breathe well underwater. After leaving the bedroom, the kids continued on into the basement, where they noticed a rake on top of a table. The rake felt heavy to hold and was brown in color.

They also carefully mixed up the nature of the counterintuitive ideas. They hypothesized that there were basically three varieties of rules to be broken – physics, biology, and psychology. In the third trial, the objects broke all three rules. So, for example, the hammer/rake was described as one that could “that could see into the future, could breathe well underwater, and could travel back and forth in time”.

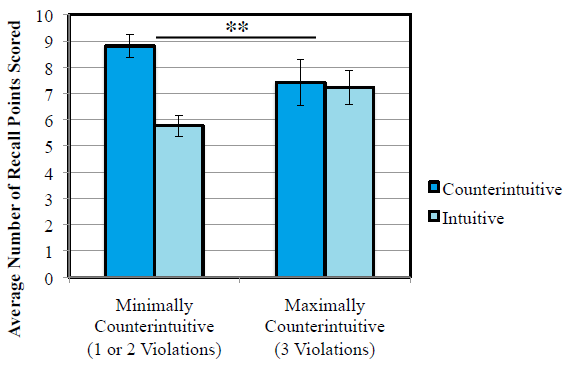

What they found was that counterintuitive objects were indeed more memorable than normal objects. Not only could the children remember the objects better, but they could list around 50% more of their characteristics. Although their memory faded over the next week, it did so at the same rate for normal and counterintuitive objects.

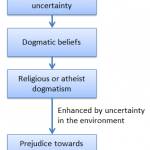

They got pretty much the same result for the first two experiments, in which the abnormal objects had either one or two counterintuitive characteristics. But, surprisingly, there was no effect in the third. As you can see in the graphic (which pools experiments one and two), they recalled normal objects equally well as those which and those which violate all three rules (physical, biological, and psychological).

The authors explain these results in terms of relevance theory. What they say is that there is nothing particularly magical about having two, rather than three, counterintuitive characteristics.

Rather, what is important is that the children can understand the relevance of the object – and to do that they need to combine what they hear with their prior knowledge. When all three rules were violated, there were no ‘natural’ domains left for the generation of inferences.

And the relevance of all this to religion? Well, they conclude that:

Like adults, children demonstrate superior immediate as well as delayed recall of minimally counterintuitive concepts, but not extremely counterintuitive concepts, compared to intuitive concepts embedded in the context of a fictional narrative. Children therefore seem to be sensitive to conceptual counterintuitiveness, an important developmental continuity in specific cognitive biases that account for supernatural beliefs.

![]()

Banerjee K, Haque OS, Spelke ES (2013). Melting Lizards and Crying Mailboxes: Children’s Preferential Recall of Minimally Counterintuitive Concepts. Cognitive science PMID: 23631765

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.